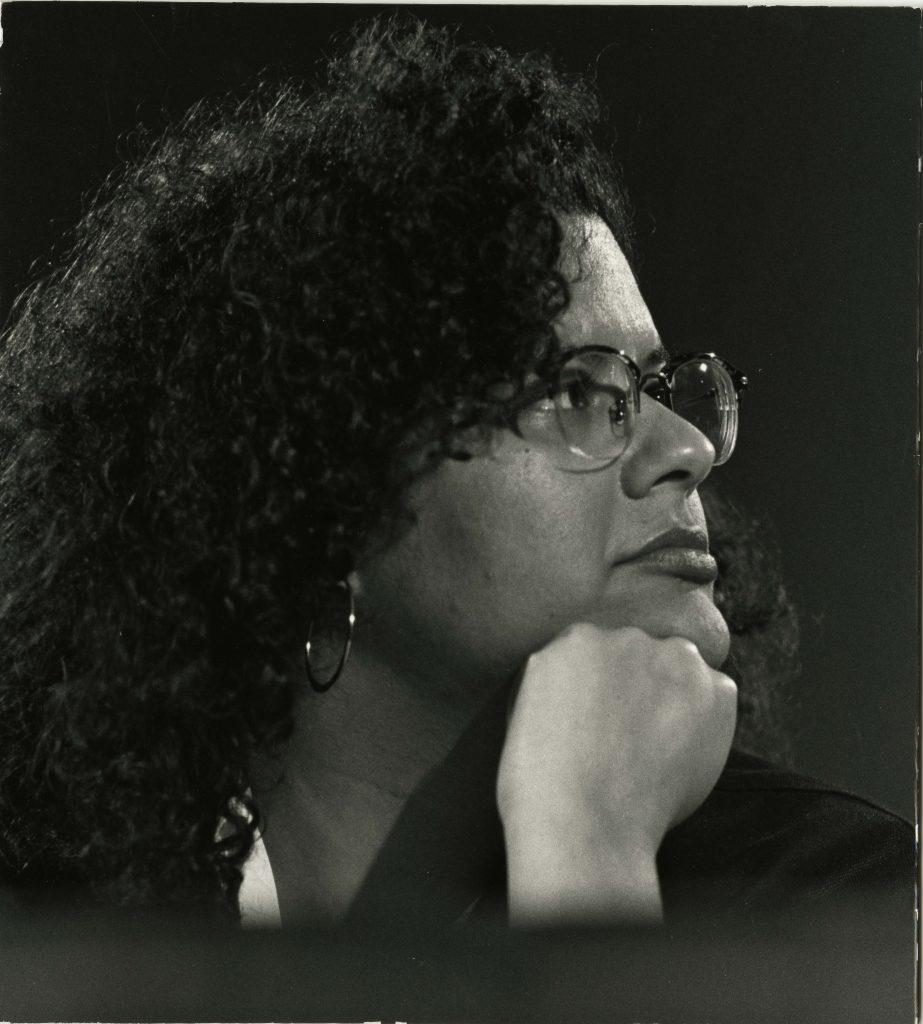

Elizabeth Alexander

Elizabeth Alexander is a renowned poet, essayist, educator, feminist, and cultural advocate. She has published several books of poetry, including The Venus Hottentot, Body of Life, and American Sublime, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer prize in 2005. Dr. Alexander read “Praise Song for the Day” at the inauguration of President Barack Obama in 2009. Her memoir, The Light of the World, was a finalist for the Pulitzer prize in 2015. She has taught at Columbia and Yale University, and currently serves as the President of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Her poetry covers a wide range of themes, including meditations on popular culture, deep explorations of personal experience, reconstructions of dream sequences, and historical reclaimations.

In works such as The Venus Hottentot, she recovers the undertold histories and silenced voices of the past, and delves into the gaps and silences of the archive. As she notes, “The historian laments caesuras in the historical record; the artist can offer deeply informed imagining that, while not empirically verifiable, offers one of the only routes we may have to imagine a past whose records have not been kept precious.”[1]

In her collection, Antebellum Dream Book, as Dr. Alexander notes, she explores how "Race, gender, class, sexuality– our social identities– exist and have been 'always already' constructed in the dream space... Yet social identity, in unfettered dream space, need not be seen as a constraint but rather as a way of imagining the racial self unfettered, racialized but not delimited."[2] The forms of her poems range from sonnets, to surrealist free verse, to counter-narrative epics such as "Amistad".

In her essay collection, The Black Interior, the powerful economy of her language combines with her vivid imagery to explore an "inner space in which black artists have found selves that go far, far beyond the limited expectations and definitions of what black is, isn't, or should be."[3] Within these works Dr. Alexander often juxtaposes African American literature and popular culture, adopting a nuanced and inspired position on their interaction.

Dr. Alexander has been influenced by Rita Dove, Elizabeth Bishop, and Gwendolyn Brooks, among others. In her role as an instructor and mentor in universities and the Cave Canem Foundation, and in her role as poet and storyteller, she has deeply influenced many poets in turn.

In this interview, Meta DuEwa Jones interviews Elizabeth Alexander, touching on the themes of myth, history, colonialism, and visuality in her work. She also discusses her need for strong self-advocacy when dealing with publishing presses, the aesthetic and ideological motives behind her book covers, and her process and philosophy for writing.

Dr. Meta DuEwa Jones is a professor at UNC Chapel Hill, and a prolific theorist. She received her Ph.D. from Stanford in 2001. She has had papers published in MELUS, Callaloo, and ELH, among other journals. She has been included in several essay collections, and has published a book, The Muse is Music. Her scholarship often works at the intersection of African American literature, music, and visual art.

More Information:

Interviews:Interview with Malin Pereira. Touches on most of Alexander's poetry collections, several themes in her work, her sense of craft, and influences.

Interview with Rachel Martin. Provides background and context for Alexander's memoir, The Light of the World. Audio file included.

Interview with Peter Kunhardt. Discusses various aspects of her friendship and solidarity with Barack Obama, growing up in the Civil Rights Era, and the political climate in the U.S.

Interview with Natasha Trethewey. Alexander reads several poems, and discusses them. Links to video included.

Furious Flower Archive: Contains a short biography, and two annotated poems with videos of Alexander reading.

Selected Poems: Contains an introductory essay, with short descriptions of Alexander’s publications to date, and links to several of Alexander’s poems.

Selected Poems: Provides a selected list of poems from across Alexander’s body of work.

"The Trayvon Generation": Alexander protests police brutality and its effect on the new generation. She also muses on the beauty and depth of the TV shows and music videos that provide forms of resistance and critique. This essay won the National Magazine Award for Essays and Criticism.

"Dunbar Lives!": Explores the impact and pervasive influence of Paul Lawrence Dunbar on multiple generations of poets.

Elizabeth Alexander's professional website.

[1]:Alexander, Elizabeth. The Black Interior. St. Paul, Minnesota: Graywolf Press, 2004.

[2]:Ibid, 5.

[3]:Ibid, 5.

Preferred Citation:

Elizabeth Alexander Interview, 9/23/2004 (FF152). Transcribed and edited by Evan Sizemore, 2021-2022, part of the Mellon-funded AudiAnnotate Audiovisual Extensible Workflow Project. Based on video recordings made by WVPT to document the second Furious Flower Poetry Center decennial meeting, September 23-25, 2004. Part of the Furious Flower Poetry Center Conference Records, 1970-2015, UA 0018, Special Collections, Carrier Library, James Madison University Libraries, Harrisonburg, Virginia, media file FF152. Collection finding aid: https://aspace.lib.jmu.edu/repositories/4/resources/487.Browser Directions:

Audio and video playback is activated by the timestamped annotation section you click in. Search field will find any word or phrase in the Transcription, Speaker or Environment annotation layers. Annotation layers can be ordered by Time (default), Annotation contents or Annotation layer labels by selecting the up/down arrows on the right. Speaker and Transcription layers are matching color-coded to facilitate reading.| Time | Annotation | Layer |

|---|---|---|

| 6:29 - 6:30 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 7:42 - 7:43 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 15:52 - 15:53 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 20:01 - 20:02 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 20:32 - 20:34 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 28:25 - 28:26 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 36:27 - 36:28 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 36:39 - 36:41 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 36:44 - 36:45 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 36:47 - 36:48 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 36:58 - 36:60 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 38:20 - 38:26 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 0:07 - 0:09 | -a, D-u capital E-w-a, J-o-n-e-s. | Transcription |

| 0:12 - 0:18 | Elizabeth Alexander. E-l-i-z-a-b-e-t-h, A-l-e-x-a-n-d-e-r. | Transcription |

| 0:18 - 0:32 | All right. Wow. Elizabeth, I wanted to start out by asking you a question that it seems to me your work really bears to mind. And it's about the relationship between your work and | Transcription |

| 0:32 - 0:34 | the African diaspora, | Transcription |

| 0:34 - 0:43 | particularly one of the things that I noticed about your work is that you really kind of both embrace ideas about race, but also question the boundaries of it. | Transcription |

| 0:43 - 0:53 | If you think about "West Indian Primer," where you're talking about both your Jamaican ancestry and then how it moves beyond that, or if you think about your poem for Nelson Mandela, where you start | Transcription |

| 0:53 - 1:05 | talking about, you know, "I am a Black daughter," but in a way that connects to the South African president, and in an interesting way. Could you talk about the relationship between your work and a | Transcription |

| 1:05 - 1:07 | diasporic context? | Transcription |

| 1:07 - 1:17 | Well, that reading that you just gave of that line, "I am a Black daughter," that break-- It seems to me, and I'm just now thinking about this, echoes Gwendolyn Brooks' great poem | Transcription |

| 1:17 - 1:29 | where she talks about "I am a Black," "I am one of the Blacks," where she feels that to be called merely African American is limiting and almost in a way euphemistic. That it skips over an | Transcription |

| 1:29 - 1:34 | understanding of how we are all connected to each other, across the globe. | Transcription |

| 1:35 - 1:47 | Sometimes in our actual histories, in the case of the Jamaican grandfather there's a lot of personal history in my poems as you know, or in newer poems. My husband is from Eritrea, so now I have a | Transcription |

| 1:47 - 2:01 | whole East African connection going on. But in a way, I think what we learn from those real histories is how complicated and sometimes nostalgic and sometimes full of fantasy, the idea of Africa is | Transcription |

| 2:01 - 2:02 | for us. | Transcription |

| 2:03 - 2:14 | You know, and I think that as African Americans, we have always tried to connect to that idea, because so much has been cut off and interrupted. But at the same time, it's a fantasy, | Transcription |

| 2:14 - 2:26 | though I think it is a heartfelt and beautiful fantasy that has led many of us, myself included, to reading and learning and reaching out and exploration and trying to theorize in very personal terms: | Transcription |

| 2:26 - 2:32 | What does it mean to be African people in this diaspora all across the world? | Transcription |

| 2:32 - 2:46 | I think also one of the beautiful realities of the United States, and for me of growing up in Washington, DC, is that you met Black people from all over the world. And that's something I touch on as | Transcription |

| 2:46 - 2:53 | well, something that was very important to my own African American grandmother growing up in Washington, DC. | Transcription |

| 2:53 - 3:06 | She would go and sit on the steps of embassies, because it let her imagine the world. And so that was a fortunate thing to grow up with: just that sense that we are, we are a multi-people. | Transcription |

| 3:07 - 3:17 | It's-- I love hearing you talk about that. Because in that poem that, where you actually invoke your grandmother sitting on the steps of embassy row, you have the line where you talk | Transcription |

| 3:17 - 3:27 | about what is a princess like in 'Feminist Poem Number One', what is, uh, what your grandmother would call and say to her-- her international friends, I am an American Negro, right, and what is an | Transcription |

| 3:27 - 3:33 | American Negro princess? And so in some ways, I think that hearing you talk about that-- | Transcription |

| 3:33 - 3:44 | and then in that same poem you actually refer to your husband and then talk about, you know, as an Abyssinian. And so its interesting how, within the context of one poem, both in terms of gender | Transcription |

| 3:44 - 3:53 | relationships, in terms of how that intersects our ideas about race and our ideas about kind of connections to Africa, that all gets kind of wrapped up into that, | Transcription |

| 3:53 - 4:05 | as well as class, right? Because anytime you kind of invoke these ideas about the princesses, it's the sense of the grandmother who wants to travel to see the world and you have traveled to see the | Transcription |

| 4:05 - 4:11 | world, right. Within the context of the line, for the poem the husband that takes you to the airport for a passport, which means of course that you're-- | Transcription |

| 4:11 - 4:12 | Going somewhere. | Transcription |

| 4:12 - 4:24 | You're going somewhere, right, and eventually coming back. And so I think that's really a useful way to think about it. But even domestically, I find that your work covers so many | Transcription |

| 4:24 - 4:37 | different kinds of Black artists and authors and photographers and athletes from Mohammed Ali to James Van Der Zee to Paul Robeson to Romero Bearden, | Transcription |

| 4:38 - 4:51 | and I'm wondering if you'd be interested in talking a little bit about, about myth, right, and Black mythic figures and major historical figures that seem to occur in your work. And I note that my | Transcription |

| 4:52 - 5:03 | list-- at this moment I'm using Black male figures because we started, um I moved in a bit of a different direction, but even your, in, Nat Turner poem. Right? So if, would you comment on that? | Transcription |

| 5:03 - 5:17 | Well yeah, I mean, I think our history, our culture is so rich, it's so under explored, it's so distortedly imagined, that it just has always seemed to me that that is an infinite | Transcription |

| 5:17 - 5:30 | mother lode for poetry. I think in some ways, what that speaks to biographically is that I spent a lot of time in school and in universities, although when I think about the reading, that gave me my | Transcription |

| 5:30 - 5:34 | information, very often, it was actually autodidactic study, | Transcription |

| 5:34 - 5:49 | it was not always what I was learning in school. But nonetheless, that context, that idea of reading to know, reading as experience that is deeply, deeply felt, and taken in reading as being-- and | Transcription |

| 5:49 - 5:57 | learning, as somehow on a, an equivalent plane to the things that you know from living your life without books. | Transcription |

| 5:57 - 6:11 | You know, to those of us for whom culture is that important, I think it's important to assert that it's lived life, it's real experience. So calling all of that in, being a scholar of African American | Transcription |

| 6:11 - 6:22 | culture, you know, it's what I teach, it's what I've been thinking about for a long time, I find that poems are a great place to work with that. That said, this whole idea of myth, you know, I, the | Transcription |

| 6:22 - 6:23 | word Abyssinian, | Transcription |

| 6:23 - 6:23 | Yes. | Transcription |

| 6:23 - 6:26 | You know that that's, that's an old timey word, | Transcription |

| 6:26 - 6:26 | Right, of course it is! Exactly. | Transcription |

| 6:26 - 6:29 | That's not what you call people today, from Eritrea. | Transcription |

| 6:29 - 6:31 | No, not at all! Of course, of course, I do know that, so. | Transcription |

| 6:31 - 6:41 | So you know, that whole, you know that to me-- yeah, I think where did it come from? That was a magical word. One of those sort of elsewhere words, one of those elsewhere Black | Transcription |

| 6:41 - 6:49 | people words, that has appealed to me from God knows what sources from as long as I can remember. | Transcription |

| 6:49 - 7:01 | Yes, yes. Thank you so much. Well, it's interesting hearing you talk about kind of-- in that context, you being a scholar of African American culture, and a teacher in points being | Transcription |

| 7:01 - 7:11 | the space where you're able to kind of explore this mother lode, because I'd actually like to talk a little bit about your newest work, 'The Black Interior'. And one of the things, you know, first off | Transcription |

| 7:11 - 7:18 | that is different, right, is that it's a collection of essays obviously, unlike your previous three books before that. | Transcription |

| 7:18 - 7:31 | And it strikes me that it is at once both scholarly, but also attempting to speak to a larger community that is not just dealing with issues of books, right, we have essays in there, one on Julia | Transcription |

| 7:31 - 7:41 | Cooper, of course, so that's definitely in the kind of intellectual or readerly tradition. But you have an essay on Denzel Washington, right? You have an essay on Rodney King. You have an essay, my | Transcription |

| 7:41 - 7:42 | goodness on Jet, right? | Transcription |

| 7:42 - 7:55 | "Notes Toward a Notion of Race-Pride." And so there's a way in which I really see your work as working with both, kind of, the African American scholarly tradition in terms of literary culture, but | Transcription |

| 7:55 - 8:09 | also and I think in important ways, more broadly, popular culture, right, in ways that I think, are useful for students, right? Because I know that, that you also teach. Could you talk about kind of | Transcription |

| 8:09 - 8:16 | the role that you see Black Interior playing in the trajectory of your work as a writer? And-- | Transcription |

| 8:16 - 8:26 | Yeah. Well, I mean, I think one of the things, you know, when you're taught close reading as a method in graduate study and undergraduate study English classes, it should be | Transcription |

| 8:26 - 8:29 | applicable to anything that constitutes a text. | Transcription |

| 8:29 - 8:29 | Yes. | Transcription |

| 8:30 - 8:42 | So there was actually a wonderful article by Stanley Fish, your UIC colleague, at, in the New York Times where he was-- had his students do close readings of a speech by Bush, a | Transcription |

| 8:42 - 8:52 | speech by Kerry. And he talked about repetition, assonance, all the, the-- what we think of as poetic devices of how people do or don't get their message across. | Transcription |

| 8:52 - 9:04 | How language works on us. So I think those tools, we should be able to turn them anyplace. And while I do think that there are all kinds of things that you can say about, you know, "poetry is not | Transcription |

| 9:04 - 9:18 | Jet magazine." But, at the same time, how does our culture manifest itself? How does it live in people who don't necessarily call themselves professional artists? And how do a lot of the issues | Transcription |

| 9:18 - 9:22 | that are of importance in our poetry and in our popular culture cross back and forth. | Transcription |

| 9:22 - 9:38 | I'm very interested in that. The book, as you know, was a long time coming, and in many ways that long time is a testimony to the challenges of finding a prose voice. You know, when an academic, a | Transcription |

| 9:38 - 9:50 | more conventionally academic voice didn't feel like a jacket that fit. And at the same time, I wanted to bring in what I know as an artist, how I look at the world as an artist, | Transcription |

| 9:50 - 10:02 | and I wanted to operate in a tradition of belles lettres that is exemplified by people like June Jordan, who's a very, very important figure to me, and who's an incredibly important essayist, and I | Transcription |

| 10:02 - 10:07 | believe, has published more essays than any Black woman in history. | Transcription |

| 10:07 - 10:08 | Yes. | Transcription |

| 10:08 - 10:10 | I'm pretty sure that that's, that that's true. | Transcription |

| 10:11 - 10:26 | And so what does it mean to, in the way that I love, to listen to a smart person with a wide field of reference, hold forth. Felicitously. I wanted to be that person in writing. | Transcription |

| 10:11 - 10:11 | Yes. | Transcription |

| 10:11 - 10:44 | And I think that actually also within Blackness, we, we have so many great raconteurs, we have so many oral geniuses who can hold forth, in a way that is just amazing. And so I think that somehow also | Transcription |

| 10:44 - 10:57 | those patterns of address and argument were somehow underneath and in there as well. But finding that voice was challenging. And now that the book is out there, you know, my, my wish and my hope is | Transcription |

| 10:57 - 11:01 | that it find its readers. And I think that's a slow process too. | Transcription |

| 11:01 - 11:02 | Oh, absolutely, absolutely. | Transcription |

| 11:02 - 11:03 | Yeah, but that's okay. | Transcription |

| 11:03 - 11:13 | Right. Well, I-- well in, within the context of the readership or audience of 'Black Interior', I think different people will come to the book with different needs and expectations. | Transcription |

| 11:13 - 11:23 | And so the nice thing about kind of the aspect of it being a work that looks at different aspects of Black culture in very diverse ways. | Transcription |

| 11:23 - 11:34 | And also, I think, using a language that is not an academic straightjacket, you know, in terms of, as a scholar of African American literature, the tradition, in terms of the scholarly tradition, | Transcription |

| 11:34 - 11:40 | there's certain expectations about language and kind of heightened language, or what is recognized or thought of as theoretical language. | Transcription |

| 11:40 - 11:53 | And yet, I find in 'The Black Interior', if you think, for example of your essay on Michael Harper, who I know has been an influence on you, that there is a way in which you, you use insightful close | Transcription |

| 11:53 - 11:60 | readings, right, of some of his, of his poems from 'Dear John, Dear Coltrane', and poems, on Bessie Smith, for example, | Transcription |

| 12:01 - 12:15 | but not terminology, that someone who has not taken, you know, American poetry 101 at Yale University would not be able to understand. And I think that's really important terms of thinking about kind | Transcription |

| 12:15 - 12:22 | of the artist and her relationship to community, right, and to audience in really, really useful ways. | Transcription |

| 12:22 - 12:33 | And I think also there's something interesting, I haven't, I'm just thinking of it this very moment, but something interesting about hierarchy and apprenticeship, in the ways that | Transcription |

| 12:34 - 12:45 | people are quoted, other experts and colleagues are quoted in the essays. But my dad read some of them in an earlier phase, he said, Why do you have to quote 10 people to say what you're trying to | Transcription |

| 12:45 - 12:48 | say? Just say what you're trying to say, and-- you're a grown up. | Transcription |

| 12:48 - 12:49 | Right. | Transcription |

| 12:49 - 12:57 | Say what you're trying to say. But of course, you know, in, in academic writing, you have to quote 10 other people, who said what you said first, in order to say what you have to | Transcription |

| 12:57 - 13:14 | say. And yet I do think that there is something within our oral communities about earning the right to speak, and about moving through ancestral wisdom and knowledge in order to have your moment to | Transcription |

| 13:14 - 13:21 | hold forth. So I think that there are different ways of sort of moving through those channels, to your moment in the sun. | Transcription |

| 13:21 - 13:31 | Oh, I'm glad you mentioned that. Because when you think about the kind of oral communities or oral culture in the way that it's associated with Black culture as an oral culture. | Transcription |

| 13:31 - 13:37 | Though, of course, in terms of scholarship, people are questioning that as a too easy identification. | Transcription |

| 13:37 - 13:52 | But one thing I noticed in your poetry is that, and you mentioned this at a conference at Yale a few years ago, where you're talking about kind of giving voice to Black female figures within our | Transcription |

| 13:52 - 13:59 | history, that you seem to not be able to find in the historical record, a record of their voice, right? And so, | Transcription |

| 13:59 - 14:09 | you have the poem "Yolande Speaks" right, in which you think about all the literature about Dubois, and even though you know, Gerald Horne has done a wonderful biography of Shirley Dubois, that | Transcription |

| 14:09 - 14:23 | Dubois' daughter, right, his only daughter, we don't hear her voice as much in the historical record. And there's a there's a way in which, you know, poems such as that where you have her not only | Transcription |

| 14:23 - 14:25 | have a voice but a perspective, right? | Transcription |

| 14:25 - 14:37 | She's like: "I've laughed/ at my father's gloves// and spats," which both humanizes him but also gives her kind of a sense of distance from him to kind of have a perspective on, on him. Or your, your | Transcription |

| 14:37 - 14:49 | first book of poetry, The Venus Hottentot, which, which opens with, you know-- although it opens with Cuvier by the time we get to Saartjie Bartman's voice, right, you have her being | Transcription |

| 14:49 - 14:57 | insistently multilingual, right? I speak English, I speak French, I speak Dutch and I even speak "languages Monsieur Cuvier/ will never know have names". | Transcription |

| 14:58 - 15:12 | There's a way in which I think that your work really does speak to the need for an awareness of this kind of orality as an aspect of Black culture without simplifying it. | Transcription |

| 15:12 - 15:27 | Mm hmm. Yes. And I think also with that moment in Venus Hottentot, the idea that we always are trying-- we always know more than we manifest. And that really interests me, both | Transcription |

| 15:27 - 15:36 | with myself, in my own continual-- I think it's a lifelong process of coming to voice, you know. You get there, okay, but then you keep moving forward, | Transcription |

| 15:36 - 15:50 | and really trying to process and distill all the knowledge and all the wisdom. But we always know more than we manifest. And she is a great exemplar of that. And I think that's a very interesting | Transcription |

| 15:51 - 15:52 | secret weapon. | Transcription |

| 15:52 - 15:53 | Yes, yes. Absolutely. | Transcription |

| 15:53 - 15:54 | That we need to think about. | Transcription |

| 15:54 - 16:04 | Absolutely. I wanna actually shift to talk about the visuals, [inaudible] by talking about the oral. And I brought with me, my beloved copies of, | Transcription |

| 16:04 - 16:16 | The babies! I'm sure they're your babies, but my copies of them. My duplicates, and one thing that really strikes me is your-- the, and I don't know what degree of control you have | Transcription |

| 16:04 - 16:04 | The babies. | Transcription |

| 16:16 - 16:27 | over this, whether it's your editors' choices, or whether you're involved in the selection of this, but the covers of your books, right, and the beautiful artwork that has-- and Black artwork, you | Transcription |

| 16:27 - 16:28 | know, in particular-- | Transcription |

| 16:28 - 16:32 | that has been a part of the process of your books. And I wondered if you could talk-- | Transcription |

| 16:32 - 16:33 | Yes, absolutely. | Transcription |

| 16:34 - 16:39 | a bit about each one. And I'm missing, I didn't bring with me, it's back in my office, the original, right, copy of The Venus Hott-- | Transcription |

| 16:39 - 16:40 | But we can talk about that. | Transcription |

| 16:40 - 16:51 | But if we could, I thought it would be really useful. Because so much of your work-- Although I've made that kind of oral comment, there's also a way in which you have so many poems | Transcription |

| 16:51 - 17:03 | that really deal with the visual image, right, and the concrete visual image, with visual artists, Bearden, Monet and so forth. The photographers. But, but there's a way in which I sense your work, | Transcription |

| 17:04 - 17:13 | and certainly in essays in The Black Interior, where you talk about how do Blacks relate to kind of the distortion of images of ourselves, | Transcription |

| 17:13 - 17:19 | and culture and-- without feeling the imperative to just only create positive images. | Transcription |

| 17:19 - 17:20 | That's right. | Transcription |

| 17:20 - 17:25 | So if you could just talk about your book covers and visuality in general, I'd appreciate it. | Transcription |

| 17:25 - 17:38 | Well, I've been very aggressive about controlling that. And with the first cover of The Venus Hottentot, that was University of Virginia press, many many years ago. And the | Transcription |

| 17:38 - 17:41 | first cover that was-- I thought, let's see what they come up with. | Transcription |

| 17:42 - 17:54 | As much as art is so important to me and as much as beautiful books are important to me. And what they came up with was a baby aspirin colored cover with scallop shells alluding as best I could see to | Transcription |

| 17:54 - 18:05 | Venus de Milo rising up out of the sea. And I thought, okay, so if after reading that poem, that is the title poem of that book, all-- it sort of proves the thesis. | Transcription |

| 18:05 - 18:06 | Yes. | Transcription |

| 18:06 - 18:18 | You know, and what you see and what you imagine, is Venus de Milo coming out of the sea, and that the color in which you cast these poems is baby aspirin, pinky-peach. | Transcription |

| 18:18 - 18:18 | Yes, yeah. | Transcription |

| 18:19 - 18:26 | I got to take control of this. We, you can't sort of negotiate with that. You can't work with that. That's too far out. | Transcription |

| 18:26 - 18:27 | That's so true. | Transcription |

| 18:27 - 18:38 | So the the painting that I chose was a painting by Charles Alston, who's my great uncle, my mother's uncle, and it's called ballet dancer, and it's a picture of a Black woman-- | Transcription |

| 18:38 - 18:51 | too bad the picture couldn't have been in color because you can see it's sort of yellows and olives. She looks a bit whiter colored than she actually is in the reproduction, but she has a kind of | Transcription |

| 18:51 - 18:53 | physical composure. | Transcription |

| 18:53 - 19:04 | That seemed to me to be very important as that relates to The Venus Hottentot. What does it mean to be that woman who's-- she's in leotards, her body is outlined and exposed, but yet, even though you | Transcription |

| 19:04 - 19:13 | are being watched, your inner life is your own. That was what I thought was in that implacable face in that, in that painting. | Transcription |

| 19:14 - 19:24 | And so ever after, you know I just, it was with 'Body of Life' which is Tia Chucha press, they were very excited to have me find my own cover, and this is by a great painter, who's a friend of mine, | Transcription |

| 19:24 - 19:38 | Kerry James Marshall. And there's a lot of romantic dynamics in this book and this painting is called "Could This be Love". And just a fabulous painting with so many small details that you can just | Transcription |

| 19:38 - 19:39 | about make up: | Transcription |

| 19:39 - 19:51 | the calendar stained with her menstrual blood, the sculpture, the Africanesque sculpture in the background echoing her form. All that Kerry James Marshall does with the black black that is not the | Transcription |

| 19:51 - 20:08 | color of anyone, but is a color of sort of mythos in a way. The songs in the background, he's saying, "What a woman, what a woman, what a woman." So there's just a lot you know, the, the Vodoun heart | Transcription |

| 20:08 - 20:09 | in there. | Transcription |

| 20:09 - 20:24 | So much going on, a very talky painting in a way that I think, communicates nicely with the paintings inside. Then in 'Antebellum Dream Book' again, the first cover that was given to me-- I said | Transcription |

| 20:24 - 20:31 | again, I'm at a new press, a press that I love, let me see what they do. And it was a picture of, you know I said it looked like the cover to Sounder. | Transcription |

| 20:32 - 20:32 | Oh my goodness. | Transcription |

| 20:32 - 20:44 | There's a Black girl on a porch, screen door, basket of produce. And I said, so how do you read that book and make that cover? Again, it speaks to me to-- how are they seeing us? | Transcription |

| 20:44 - 20:45 | Yes, absolutely. | Transcription |

| 20:45 - 20:55 | How, with, with the book in-- and so I said, can't work with this, we got to just start all over again. And this painting is Bob Thompson's "The Garden of Music," which I just | Transcription |

| 20:55 - 21:04 | adore. And because there are dream poems in the book, I felt that there was a very dreamlike quality, a surreal quality to these wonderful purple people. | Transcription |

| 21:04 - 21:17 | And, you know, that, that it was a dreamscape in a way that I thought worked with the books, the poems inside. And then with Black Interior, we've spoken at the conference, Sonia Sanchez mentioned, | Transcription |

| 21:18 - 21:23 | the great Elizabeth Catlett. And this image is called "The Black Woman Speaks". | Transcription |

| 21:23 - 21:24 | So appropriate. | Transcription |

| 21:24 - 21:33 | You know, and there it is. And as I talk about in the book, what you can't see on the picture, on the side, there is a sort of a spiral that's inscribed on her temple, if you were | Transcription |

| 21:33 - 21:46 | to have a side view. And you know, the spiral is a symbol of infinity, and it seems to me that that it also suggests, it almost-- as though it's a drawing of what's inside the Black woman's head. | Transcription |

| 21:46 - 21:46 | Yes, yes. | Transcription |

| 21:46 - 22:01 | An infinite, infinite spiral. And Catlett made this work in about 1970, when she herself was a very, very mature artist, mother of grown children. Which connects with my | Transcription |

| 22:01 - 22:16 | conversation of Gwendolyn Brooks, at the same point more or less in her life. A very senior woman, a very acclaimed artist, nonetheless subject to change, responsive to the times. | Transcription |

| 22:16 - 22:18 | Willing to evolve. | Transcription |

| 22:18 - 22:28 | Willing to evolve. And I think that, that was-- in addition to just that it's, it's a ravishing piece of work, it's a beautiful, beautiful sculpture. And it's it's also a nice | Transcription |

| 22:28 - 22:40 | picture of a sculpture, which is hard to do sometimes. But to me, you know, I'm interested in artists' careers over time, you know, want to be in it for the long haul. And so and that's why it's so | Transcription |

| 22:40 - 22:42 | fortunate to be here with people like Sonia and Lucille. | Transcription |

| 22:43 - 22:45 | Because you see that long, tradition. Long tradition. | Transcription |

| 22:45 - 22:53 | Long, and you know, and that these are people who have also-- I have small children, these are people who have raised children, who have made a life in the arts. | Transcription |

| 22:53 - 22:58 | And mothers, and wives, and partners and all of these things and still been artists, | Transcription |

| 22:58 - 22:58 | Yes. | Transcription |

| 22:58 - 23:03 | And scholars, and in so many ways and theorists of Black culture, right. And so. | Transcription |

| 23:03 - 23:10 | Yes, yes, yes. And so that's, those are the women that give me power, you know. | Transcription |

| 23:10 - 23:22 | Me as well. I can definitely identify with that. Thank you so much for that. I want to ask a more just simply basic question, since I've been-- How do you know when you are ready to | Transcription |

| 23:22 - 23:24 | start or finish a poem? | Transcription |

| 23:25 - 23:37 | Ooh. Well at this conference I have felt really ready to start a lot of poems. I think that being around poetry and being around people who make poetry makes new poems happen, you | Transcription |

| 23:37 - 23:51 | know. It's like this incredible, biodynamic thing that, that happens, you just sort of-- you take a word, you take a line, you take a sort of a modal imprint, and the poems are ready to come. | Transcription |

| 23:52 - 24:01 | And then for me, as for all of us, there's always the question of time, and where to find-- you know, I love that Lucille Clifton, when she was talking about what it was to have four children in | Transcription |

| 24:01 - 24:05 | diapers at the same time. And she said to the audience, you think you're busy? | Transcription |

| 24:05 - 24:06 | Right. Right. Absolutely. | Transcription |

| 24:06 - 24:17 | And she has spoken about actually how the ideal circumstances for her to write poetry became domestic chaos. Because that's what it was. You know, that if you know, she says, | Transcription |

| 24:17 - 24:27 | one-- you're at the kitchen table, and one child's got the measles and the other child's got the homework and that everything is going on. Nonetheless, you somehow make that space. And I am working to | Transcription |

| 24:27 - 24:36 | do that as I think whether or not we have children we're always, in the midst of our lives, we all have to make a living. No poet is supporting him or herself solely by the word. | Transcription |

| 24:36 - 24:50 | So you're trying to make that bubble, or develop the habit that says, at least in my bag, the notebook is always there. Although, because driving ends up sometimes to be the only free time there is. | Transcription |

| 24:51 - 24:60 | Can't quite write the things down as well, you know, on the road, as well as you would like to. So it's that feeling though, which I'm having now which I'm having after this conference of being full | Transcription |

| 24:60 - 25:01 | up. | Transcription |

| 25:02 - 25:14 | And then you know, then there's process, process, process. But then the ready to be done with it is a tricky thing as well. I was speaking with some students recently about how you sort of go as far | Transcription |

| 25:14 - 25:26 | as you can, and then you leave it and come back to it after it's had time to sit. And then you can more clearly see, okay, was I just tired? Was I just out of ideas? Or maybe this really is done. | Transcription |

| 25:27 - 25:40 | Or maybe now I can see what the final tweak is. And I have poems that have remained in folders for years and years and years and years, snippets for years, that then you find, okay, this is how I can | Transcription |

| 25:40 - 25:42 | use this. This is how I can complete this. | Transcription |

| 25:43 - 25:45 | Do you revise your work alot? | Transcription |

| 25:45 - 25:57 | Oh, yeah. Yeah. But I mean, hopefully, what happens when you get lucky, is that there's a rush in the beginning, that at least gets a large chunk sketched out. Though, that then | Transcription |

| 25:57 - 26:05 | also will be revised and revised and revised. But I like when there's enough-- that mysterious enoughness to put the poem over the cliff. | Transcription |

| 26:06 - 26:06 | Absolutely. | Transcription |

| 26:07 - 26:17 | I can feel when I'm like, uhh, I'm not at the edge of the cliff. So I'm not there. And sometimes that stuff gets wasted or lost. But you know, one must be Zen about these things. | Transcription |

| 26:18 - 26:19 | You know, nothing is wasted. | Transcription |

| 26:19 - 26:30 | Nothing, nothing, nothing. And do you have a favorite poem? Is there a poem of yours that you just-- I know, for example, I've memorized a number of your poems but this is as someone | Transcription |

| 26:30 - 26:40 | who's not-- is coming to it from a different perspective. And I'm just curious if, if you've memorized some of yours, do you have any poems that you just go like, I love this? Or is it each new poem | Transcription |

| 26:40 - 26:42 | is the favorite, or--? | Transcription |

| 26:42 - 26:54 | Yeah, yeah. There are some that I'm extra proud of mostly because of the work. You know, 'The Venus Hottentot', I worked very, very hard on it, to keep those two voices distinct | Transcription |

| 26:54 - 27:08 | and consistent, and to really take myself into a very, very other world of imagination. So I was proud of it as work. In this new collection, I have a really long, a 25 page poem on the Amistad. | Transcription |

| 27:09 - 27:21 | I've been working on it for years. I've done a ton of research. You know, I'm proud of it, because it was hard, good work. And I tried to be meticulous and faithful. I mean, you know, you always are, | Transcription |

| 27:22 - 27:27 | but maybe it's the-- it's easier to be proud of the sort of bigger projects in a sense. | Transcription |

| 27:28 - 27:46 | But I think also moments in poems where I know I have been true, when I could have been cute? Meaning, just clever or, you know, a fancy word but maybe not the right word, or you know, a wonderful | Transcription |

| 27:47 - 27:52 | music, but only for its own sake, and not furthering anything in the poem. | Transcription |

| 27:53 - 28:07 | You know, moments where I have avoided cuteness or showiness, which has been ingrained in me as a modus operandi from a very early age. You know, my grandmother, if anyone said, you know, to any child | Transcription |

| 28:07 - 28:21 | in her world, you know, oh, you know, what a pretty little girl. 'And she is a very nice child'. You know, 'and she is a very bright girl. And she's a very kind girl'. That was-- and you know, with | Transcription |

| 28:21 - 28:24 | such a voice that said, you know, so don't even try. | Transcription |

| 28:24 - 28:26 | You can't even try to count on the cute. Don't count on the cute. | Transcription |

| 28:26 - 28:37 | Don't even puff up. Don't even puff up, you know, because it's the values of what make you a good human being. That that's what's important. So I think that as-- that's an, | Transcription |

| 28:37 - 28:44 | actually a very useful poetic value as well too. Just because you can doesn't mean you always should. | Transcription |

| 28:44 - 28:55 | And so that you see that translation between them. Well, I actually have a poem that I'd like to hear you talk about, and it appeared in The New Yorker. That is, well, I have a | Transcription |

| 28:55 - 29:05 | number of favorite things, poems, on your corpus. But it's certainly one that I would love to hear you talk about. And it's "When". | Transcription |

| 29:05 - 29:16 | Yes, well that, just this morning at the conference, Honorée Jeffers gave a great paper about blues, sort of a manifesto on blues poetics. And she was talking about different | Transcription |

| 29:16 - 29:25 | elements that make a contemporary blues poem. Because we're at a fascinating moment, you know, we're not Langston, we're not Sterling. We're not inventing the form of the blues poem in the middle of | Transcription |

| 29:25 - 29:28 | that music being widely distributed in record form. | Transcription |

| 29:29 - 29:40 | It's incredible when you read those Hughes and Van Vechten letters, when they're sending blues lyrics back and forth. Because as, you know, it's one thing to go and the dishwasher on the ship is | Transcription |

| 29:40 - 29:45 | singing the blues. But you know, for for records to be available. I mean, these are letters in the '20s. | Transcription |

| 29:45 - 29:46 | Absolutely. | Transcription |

| 29:46 - 29:57 | So it's new so I mean, wow, it-- hats off to Langston and then to Sterling Brown for making the form in poetry, literary form that nonetheless comes out of the blues. But we're in | Transcription |

| 29:57 - 30:11 | a different moment. And what is the blues today and how is the blues aesthetic an element of African American culture that comes out in all sorts of different ways that aren't necessarily immediately | Transcription |

| 30:11 - 30:15 | identifiable as what Murray would call the blues as such, right? | Transcription |

| 30:15 - 30:26 | So she was talking about the blues, and she said that "When" was a poem that she taught as a blues poem? And I said, Well, isn't that interesting? It's a sonnet. And to me, it was a sonnet in the mode | Transcription |

| 30:26 - 30:38 | of the Hayden sonnets, specifically "Those Winter Sundays" in Frederick Douglass, which I think redefine what a sonnet can be. And then where my thinking took me, and I thought, well, what | Transcription |

| 30:38 - 30:45 | makes "Those Winter Sundays" such a great Hayden sonnet is that the blues cracked open the sonnet form. | Transcription |

| 30:45 - 30:46 | Absolutely. | Transcription |

| 30:46 - 30:51 | And literally, the blues cracks open that poem. You know, "What did I know, what did I know?" | Transcription |

| 30:51 - 30:53 | "Of love's austere and lonely offices?" Right? | Transcription |

| 30:53 - 31:04 | I mean, you know, What did I know? You can just hear it spoken like that. So that reanimated the form. And I think it got at a way of talking-- you know, if the blue note is the | Transcription |

| 31:04 - 31:14 | space between the black and the white keys, I think that the blue note is a space of nuance, that is what I'm trying to explore in that poem. | Transcription |

| 31:15 - 31:28 | It's the nuance that is very specific about talking about these particular Black men, though it begins with a sweeping sort of magical generality. "In the early 1980s, the black men/ were divine", you | Transcription |

| 31:28 - 31:30 | know, all of them, the Black men. | Transcription |

| 31:30 - 31:33 | Could you read that? Would you be willing to read it? Now, would you all mind? | Transcription |

| 31:33 - 31:34 | Yeah, sure. Should I? | Transcription |

| 31:34 - 31:35 | Yeah, I'm just-- are you gonna read it later today? | Transcription |

| 31:35 - 31:37 | I was gonna read it later today. Oh, so we don't need to. | Transcription |

| 31:37 - 31:38 | Oh, so then you don't need her to read it. | Transcription |

| 31:38 - 31:39 | Okay. All right. | Transcription |

| 31:39 - 31:39 | Oh I'm sorry. | Transcription |

| 31:39 - 31:40 | All right. No, that's okay. | Transcription |

| 31:40 - 31:41 | Okay then, yeah. | Transcription |

| 31:41 - 31:47 | Um, but so, so, you know, there's that sort of sweeping beginning and then all of these particulars about these amazing Black men. | Transcription |

| 31:47 - 31:48 | Okay. | Transcription |

| 31:48 - 31:52 | You know, their style, their brilliance, their fabulosities, you know they-- | Transcription |

| 31:52 - 31:53 | Their reading, they all quote Fanon. Right. | Transcription |

| 31:53 - 32:05 | That's right, I mean, you know, who are these men? And these were, these were-- I'm thinking specifically of a few men in the poem, particularly the poet Melvin Dixon. Who was so | Transcription |

| 32:05 - 32:16 | important to me, who died of AIDS, who, you know, to imagine him at this conference. And the likes of him, the likes of Essex Hemphill. | Transcription |

| 32:16 - 32:27 | You know, this is such a ghosty conference. And that was made visible to us last night, when we saw the people who have passed, and thinking, you know, about a June Jordan-- you know, all of the not | Transcription |

| 32:27 - 32:34 | here, not here, not here, not here. But Melvin was important to me also, because he was a real man of letters. | Transcription |

| 32:35 - 32:46 | I met him when he was on a postdoctoral fellowship at Yale when I was an undergraduate. He had already lived abroad, he had lived in Africa and France. That was just too fabulous for me, it was like | Transcription |

| 32:46 - 32:60 | the, you know, it was just very cool. And that he had translated, Senghor's work, he had translated criticism, was a poet, was a fiction writer, and didn't have any issues. You know, he said, if | Transcription |

| 32:60 - 33:04 | anyone has an issue with my working in these different modalities, that's their problem. | Transcription |

| 33:06 - 33:22 | You know, had his PhD, but just reconciled it all. And he was a very, very, very important model to me and was a kind, kind, big brother. In-- to me, he really, really was. Which is part of why I was | Transcription |

| 33:22 - 33:36 | so proud to to edit and bring out his last collection, 'Love's Instruments', a very great book. Yeah, that I'm happy is available. So he was-- anyway, he and others were behind that poem. | Transcription |

| 33:36 - 33:37 | We have time for one more. | Transcription |

| 33:37 - 33:38 | Okay. | Transcription |

| 33:38 - 33:39 | Okay, so this is the Regen-- | Transcription |

| 33:39 - 33:40 | A short question and a short answer. | Transcription |

| 33:40 - 33:42 | Okay. We'll be Chris. | Transcription |

| 33:42 - 33:50 | Okay so the short question that-- So the Chris question is the, um, well you're editing me so I can just say this, it's The Regenerating the Black Poetic Tradition question. You | Transcription |

| 33:50 - 34:02 | talked about Dixon being a big brother to you, and being so kind and generous, and so forth. And I certainly know, the younger generation of African American writers and poets, particularly, have all | Transcription |

| 34:02 - 34:05 | spoken of you so highly as a mentor, | Transcription |

| 34:05 - 34:17 | and as someone who has not only influenced them, but pushed them both in terms of the craft and the crafting of their verse. I believe it's Kevin Young, who in the anthology 'Giant Steps' says that, | Transcription |

| 34:17 - 34:27 | you know, you start that-- you're the first in that anthology by accident of your last name, but in fact, he says it's most appropriate because you really are seen as at the forefront, right of this | Transcription |

| 34:27 - 34:31 | generation of writers born from 1960 forward | Transcription |

| 34:31 - 34:47 | in that you've worked in so many genres, like Melvin Dixon, who you've spoken about, in certain ways. Could you talk just briefly about what Black poetic tradition means to you, and how you see | Transcription |

| 34:47 - 34:49 | yourself fitting within that? | Transcription |

| 34:50 - 35:04 | Well I, almost nothing makes me happier than those people recognizing, because I love them. And I can't even believe, you know, Kevin Young was in college and came to one of my | Transcription |

| 35:04 - 35:15 | poetry readings. And now I mean then he was a peer but now he's a different kind of peer. I mean, all of those people are on their second and third-- well you know, Honorée Jeffers, Van Jordan, | Transcription |

| 35:15 - 35:17 | Terrence Hayes, Natasha Tretheway. | Transcription |

| 35:17 - 35:17 | Major Jackson. | Transcription |

| 35:18 - 35:31 | I mean Major Jackson, it's, it's an incredible, incredible moment. It really, really is. And I think that we are getting, never enough, but more of the institutional support that | Transcription |

| 35:31 - 35:35 | helps make our work visible. And that's really, really important. | Transcription |

| 35:36 - 35:48 | More of our books are available in more places. That's really important. Because, you know, Third World Press can't do everything. Broadside Press can't do everything. And these presses that have | Transcription |

| 35:48 - 36:02 | excluded us need to just join the-- join the new century, you know, if they missed the last century. And that's beginning to happen, people are teaching that makes a big difference. People are | Transcription |

| 36:02 - 36:07 | distinct from each other, people are having their arguments, and that's important too. | Transcription |

| 36:07 - 36:10 | Absolutely the disagreement. I agree, and I-- | Transcription |

| 36:10 - 36:19 | So it's, it's an amazing amazing time I think and we're lucky to also have our elders with us to be able to look back and wonder. | Transcription |

| 36:19 - 36:23 | And we're lucky to have you. We really are. Thank you. | Transcription |

| 36:23 - 36:25 | Okay. Great, great. | Transcription |

| 36:26 - 36:29 | Don't move. Now I just want you looking at the camera, this is the TV tech stuff. | Transcription |

| 36:29 - 36:29 | Okay. | Transcription |

| 36:29 - 36:30 | Alrighty. | Transcription |

| 36:30 - 36:33 | Talk to each other about anything just not at the same time I'm just getting cutaways and then I'm gonna [inaudible]. | Transcription |

| 36:33 - 36:33 | Alrighty. | Transcription |

| 36:33 - 36:33 | Okay. | Transcription |

| 36:34 - 36:35 | I am so happy right now. | Transcription |

| 36:35 - 36:36 | I know! | Transcription |

| 36:36 - 36:38 | You are such a great interview. You really are. | Transcription |

| 36:38 - 36:43 | Oh, but you're interviewing me! If it were others I could be sullen and wordless. | Transcription |

| 36:43 - 36:46 | Oh, I can't imagine that as ever being possible. | Transcription |

| 36:46 - 36:48 | How can anyone not have a good conversation with you? | Transcription |

| 36:50 - 36:51 | George you can get me a shot of that [inaudible]? | Transcription |

| 36:51 - 36:55 | I'm so glad I brought the books, they're so beautiful. | Transcription |

| 36:56 - 36:57 | This is my first child. | Transcription |

| 37:01 - 37:03 | [inaudible] can maybe go to the next one. | Transcription |

| 37:01 - 37:01 | Okay. | Transcription |

| 37:01 - 37:01 | Okay. | Transcription |

| 37:01 - 37:01 | [inaudible] 'Body of Life' | Transcription |

| 37:03 - 37:03 | Body of Life | Transcription |

| 37:03 - 37:08 | [inaudible] top of it towards me. | Transcription |

| 37:08 - 37:10 | Top of it towards you. Okay. | Transcription |

| 37:33 - 37:46 | Okay. Were you able to get much over her shoulder when they were talking about [inaudible]? I love your choices. It was [inaudible] hearing the stories. | Transcription |

| 37:49 - 37:60 | Well the next one, the next book is called American Sublime from the Philadelphia Museum. And I wanted to have a, yeah, 19th century painting because of the long Amistad poem. | Transcription |

| 37:60 - 38:03 | I have to tell you something. I knew that [inaudible]. | Transcription |

| 38:03 - 38:04 | When is that coming out? | Transcription |

| 38:05 - 38:12 | One year. And that's, that's the negotiated-- the weight has been cut. Yeah. | Transcription |

| 38:13 - 38:14 | Oh, really [inaudible]. | Transcription |

| 38:14 - 38:15 | And Meta, where are you? | Transcription |

| 38:15 - 38:17 | I teach at George Washington University | Transcription |

| 38:17 - 38:18 | Do you want her to put that book down? | Transcription |

| 38:19 - 38:19 | Oh. Thank you Judith! | Transcription |

| 38:19 - 38:19 | Yeah. | Transcription |

| 38:19 - 38:25 | Just do two things! Both [inaudible]. | Transcription |

| 38:25 - 39:18 | Right. Right. | Transcription |

| 0:07 - 0:09 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 0:12 - 0:18 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 0:17 - 0:32 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 1:07 - 1:17 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 3:07 - 3:17 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 4:11 - 4:12 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 4:12 - 4:24 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 5:03 - 5:17 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 6:23 - 6:23 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 6:23 - 6:26 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 6:26 - 6:26 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 6:26 - 6:29 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 6:29 - 6:31 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 6:30 - 6:41 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 6:48 - 7:01 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 8:16 - 8:26 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 8:29 - 8:29 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 8:29 - 8:42 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 10:07 - 10:08 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 10:08 - 10:10 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 10:10 - 10:26 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 10:11 - 10:11 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 11:01 - 11:02 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 11:02 - 11:03 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 11:03 - 11:13 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 12:22 - 12:33 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 12:48 - 12:49 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 12:49 - 12:57 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 13:20 - 13:31 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 15:12 - 15:27 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 15:52 - 15:53 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 15:53 - 15:54 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 15:53 - 16:04 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 16:03 - 16:16 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 16:04 - 16:04 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 16:32 - 16:33 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 16:33 - 16:39 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 16:39 - 16:40 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 16:40 - 16:51 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 17:19 - 17:20 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 17:19 - 17:25 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 17:25 - 17:38 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 18:05 - 18:06 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 18:06 - 18:18 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 18:18 - 18:18 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 18:19 - 18:26 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 18:26 - 18:27 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 18:26 - 18:38 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 20:32 - 20:32 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 20:32 - 20:44 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 20:44 - 20:45 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 20:44 - 20:55 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 21:23 - 21:24 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 21:24 - 21:33 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 21:45 - 21:46 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 21:46 - 22:01 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 22:16 - 22:18 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 22:18 - 22:28 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 22:43 - 22:45 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 22:45 - 22:53 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 22:53 - 22:58 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 22:58 - 22:58 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 22:58 - 23:03 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 23:03 - 23:10 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 23:10 - 23:22 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 23:25 - 23:37 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 24:05 - 24:06 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 24:06 - 24:17 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 25:43 - 25:45 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 25:45 - 25:57 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 26:06 - 26:06 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 26:07 - 26:17 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 26:19 - 26:30 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 26:41 - 26:54 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 28:24 - 28:26 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 28:26 - 28:37 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 28:43 - 28:55 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 29:05 - 29:16 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 29:45 - 29:46 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 29:45 - 29:57 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 30:45 - 30:46 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 30:46 - 30:51 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 30:51 - 30:53 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 30:53 - 31:04 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 31:30 - 31:33 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 31:33 - 31:34 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 31:34 - 31:35 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 31:35 - 31:37 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 31:37 - 31:38 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 31:38 - 31:39 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 31:39 - 31:39 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 31:39 - 31:40 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 31:40 - 31:41 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 31:41 - 31:47 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 31:47 - 31:48 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 31:48 - 31:52 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 31:52 - 31:53 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 31:53 - 32:05 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 33:36 - 33:37 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 33:37 - 33:38 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 33:38 - 33:39 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 33:39 - 33:40 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 33:40 - 33:42 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 33:41 - 33:50 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 34:50 - 35:04 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 35:17 - 35:17 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 35:18 - 35:31 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 36:07 - 36:10 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 36:10 - 36:19 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 36:19 - 36:23 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 36:23 - 36:25 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 36:29 - 36:29 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 36:29 - 36:30 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 36:30 - 36:33 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 36:33 - 36:33 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 36:33 - 36:33 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 36:34 - 36:35 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 36:35 - 36:36 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 36:36 - 36:38 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 36:38 - 36:43 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 36:43 - 36:46 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 36:46 - 36:48 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 36:50 - 36:51 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 36:51 - 36:55 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 36:56 - 36:57 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 37:01 - 37:03 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 37:01 - 37:01 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 37:01 - 37:01 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 37:01 - 37:01 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 37:03 - 37:03 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 37:03 - 37:08 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 37:08 - 37:10 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 37:33 - 37:46 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 37:49 - 37:60 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 37:59 - 38:03 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 38:03 - 38:04 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 38:05 - 38:12 | Elizabeth Alexander | Speaker |

| 38:13 - 38:14 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 38:15 - 38:17 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 38:17 - 38:18 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 38:18 - 38:19 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |

| 38:19 - 38:25 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 38:25 - 39:18 | Meta DuEwa Jones | Speaker |