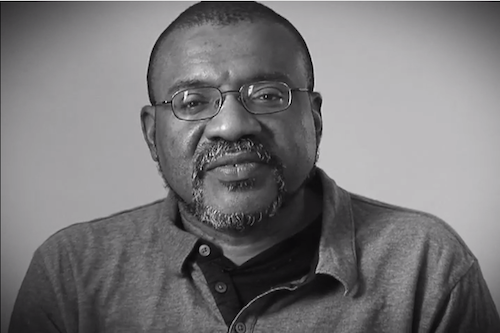

Kwame Dawes

Kwame Dawes is a prolific poet, teacher, editor, documentarian, and organizer that works closely with local communities. He has published twenty books of poetry to date, including Progeny of Air, Gomer’s Song, and Duppy Conqueror: New and Selected Poems. He has also received several awards for his work, including the Pushcart Prize for his poem, Inheritance, and an Emmy for a website based on his project HOPE: Living and Loving with AIDS in Jamaica.

Born in Ghana, and spending most of his childhood in Jamaica, Dawes works at the intersection of the various facets of his identity, calling on his memory of the various places he calls home. As he notes, "I have always lived with this sense of being inside and outside of various worlds… at once, inside and yet still able to look from outside inside."[1] In his wide panoply of work, Dawes weaves themes of nature, community, counter-narrative, Reggae, memory, and dreams together in his rich landscapes, portraits, and stories.

In his first published collection, Progeny of Air, Dawes forges deep relations between his characters, the ecological and animal worlds surrounding them, and the perverse and destructive forces of industrialism and colonialism. In Shook Foil, he explores parenting, Reggae, spirituality, and ancestrality through the vibrant tones of nature. More recently, Dawes has published novels such as Bivouac, written plays, and edited several anthologies.

In this interview with Tyehimba Jess, Dawes discusses his experience of early reggae in 1970s Jamaica, how the political landscapes he grew up with shaped his thinking and identity, the underrepresentation of Black writers and poets in the publishing industry, how he has overcome and worked to change the industry, and his passion for teaching and organizing writing communities.

Tyehimba Jess is an Alumnus of Cave Canem and NYU, working at the intersection of slam and academic poetry. His published books include Lead Belly and Olio, which won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize, among other awards. He currently serves as a Professor of English at the College of Staten Island.

More Information:

Interviews:

Interview with Walter P. Collins, III. Tells the story of Dawes’ family, situating it within the historical and political landscape of mid-20th century Jamaica and Ghana. Also touches on the poetic forms he works with, and his writing process.

Essays:

"Learning to Speak: The New Age of HIV / AIDS in the Other Jamaica": Essay, with photographs, concerning the history of the AIDS virus in Jamaica, the lived experience of those living with it, and some of the medical and emotional strategies of resistance that have formed.

"Meeting at the Crossroads: Mapping Worlds and World Literature": Considers the multiple meanings and symbols connected to the crossroads, and uses it as a metaphor to reimagine comparative literature.

"An Apologia for Caribbean Publishing": Dawes calls for more independent publishing houses and editors within the Caribbean, emphasizing the importance of independent presses to knowledge preservation and the growth of cultural capital.

Poems:

Selection containing over 80 poems chosen from Dawes’ publications, including several from his multimedia collaboration Ashes.

Selection of Dawes’ more recent poems.

Other:

Kwame Dawes’ professional website. Contains an extensive biography, links to books and poems, descriptions of Dawes’ celebrated multimedia collaborations, and contact information.

Video Lecture by Kwame Dawes and a conversation at the Library of Congress.

[1]:Dawes, Kwame Senu Neville, and Walter P. Collins. "Kwame Dawes: An Interview with Walter P. Collins, III." Obsidian 8, no. 2 (2007): 38–52.

Preferred Citation:

Kwame Dawes Interview, 9/25/2004 (FF146). Transcribed and edited by Evan Sizemore, 2021-2022, part of the Mellon-funded AudiAnnotate Audiovisual Extensible Workflow Project. Based on video recordings made by WVPT to document the second Furious Flower Poetry Center decennial meeting, September 23-25, 2004. Part of the Furious Flower Poetry Center Conference Records, 1970-2015, UA 0018, Special Collections, Carrier Library, James Madison University Libraries, Harrisonburg, Virginia, media file FF146. Collection finding aid: https://aspace.lib.jmu.edu/repositories/4/resources/487.

Browser Directions:

Audio and video playback is activated by the timestamped annotation section you click in. Search field will find any word or phrase in the Transcription, Speaker or Environment annotation layers. Annotation layers can be ordered by Time (default), Annotation contents or Annotation layer labels by selecting the up/down arrows on the right. Speaker and Transcription layers are matching color-coded to facilitate reading.

| Time | Annotation | Layer |

|---|---|---|

| 0:20 - 0:23 | [Audio cuts out] | Environment |

| 2:14 - 2:17 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 2:19 - 2:20 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 3:37 - 3:39 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 3:41 - 3:44 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 4:52 - 4:54 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 5:16 - 5:18 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 5:34 - 5:35 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 5:54 - 5:55 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 6:39 - 6:40 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 7:32 - 7:33 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 7:47 - 7:55 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 9:10 - 9:13 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 13:18 - 13:20 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 14:26 - 14:27 | [Rustling] | Environment |

| 16:39 - 16:43 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 18:22 - 18:25 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 19:04 - 19:15 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 21:33 - 21:37 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 26:26 - 26:26 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 31:15 - 31:17 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 31:39 - 31:46 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 0:06 - 0:11 | My name is Tyehimba Jess. T-y-e-h-i-m-b-a last name J-e-s-s. | Transcription |

| 0:13 - 0:20 | My name is Kwame Dawes. K-w-a-m-e D-a-w- | Transcription |

| 0:24 - 0:36 | Okay. Kwame, Tell me. Your poem "Ward 21". It was written for your brother. It seems like that would have been a painful poem to write. | Transcription |

| 0:37 - 0:49 | It's a part of a longer sequence. And it was difficult to write. It's funny, because I guess when I come to write the poem, or the process of writing the poem, you're-- I'm so sort of | Transcription |

| 0:49 - 0:60 | taken up with the processes, just the idea of the form and trying to make the thing work, that the pain of it doesn't really hit until I'm looking back at the poem and starting to contemplate it. | Transcription |

| 0:60 - 1:11 | And I'm thinking of an audience, I'm thinking of him reading it, and I'm thinking of sort of being around family who may know the poem and so on. But the stuff that is behind the poem-- that is the | Transcription |

| 1:11 - 1:19 | history, the narrative history-- is clearly painful. I mean, it was a difficult time. | Transcription |

| 1:20 - 1:32 | Because the poem tells, is part of a longer narrative about, about my younger brother who had a nervous breakdown at age 14. And the discovery 20 years later that what had happened was he was actually | Transcription |

| 1:32 - 1:36 | suffering from post traumatic stress because of some abusive situation he had been caught in. | Transcription |

| 1:37 - 1:50 | And so the, the shock of discovering that years later sent me to write the poems. In fact, I started write-- I wrote a memoir, I wrote a whole book, which I haven't published yet, but I wrote a whole | Transcription |

| 1:50 - 2:01 | book first. And then I said, you know, probably, I should do this with poetry, which might be, might give me a chance to come at it from different directions and different angles. Yeah. | Transcription |

| 2:02 - 2:03 | So has he read the poems? | Transcription |

| 2:03 - 2:14 | He hasn't read the poems. I think he's read a couple of the poems. And so, but you know, we talk about it. I mean he's, I guess he's cool with it. There's a certain kind of notoriety that | Transcription |

| 2:14 - 2:20 | comes with it as well. Everybody in the world is gonna know about him, so I guess that's good. | Transcription |

| 2:21 - 2:36 | But it is as much his story. And there's a great statement that a number of memoir writers have said, and, and I tie this with memoir, even though this is a sequence of poems, because the problems of | Transcription |

| 2:36 - 2:46 | deciding what to write about, and the problems of writing about something that is rooted in a personal history is common with both the poems and with a memoir, I think. | Transcription |

| 2:46 - 2:58 | And one of the interesting things that I was encouraged by a number of memoir writers is when they tell you that look, remember, this is your story. It's his story, but it's really my story. Because | Transcription |

| 2:58 - 3:08 | part of the tension of those poems is the way that I reacted to what he went through. | Transcription |

| 3:08 - 3:21 | Right, this combination of, I mean, anybody who has been through a situation where we, you have some kind of mental illness in the family, it's a combination of deep sorrow, incredible anger, because | Transcription |

| 3:21 - 3:34 | of this disruption, and guilt. All of those emotions are tied to me more than anything else, so that his emotional space is not as mine as mine is in the poem. So it's really my story. And so I guess | Transcription |

| 3:34 - 3:36 | I'm the one who comes off bad. | Transcription |

| 3:39 - 3:39 | Human. | Transcription |

| 3:40 - 3:41 | Human. Yeah, same thing. | Transcription |

| 3:46 - 3:52 | When you wrote it, I mean, did you have any idea of how it would be received outside of your family? | Transcription |

| 3:52 - 4:04 | No, no, no. And I don't think about that when I'm writing or when I'm working on something. I think about that only when I'm thinking of publishing it. And that's when I'm organizing it | Transcription |

| 4:04 - 4:08 | and when I'm trying to see how to cast it and so on so forth. And I'm thinking about that now. | Transcription |

| 4:09 - 4:28 | But I don't panic too much about that question. I really don't. Probably because there's no shame in it for us, you see, and that's, to me, the most important thing. And there's something liberating | Transcription |

| 4:28 - 4:39 | about-- the story ends well, put it that way. You know, it ends positively in that sense, that there's stability and there's truth, we come to truth. And that to me is very important. Yeah. | Transcription |

| 4:40 - 4:49 | Well, speaking of organizing books, etc. Correct me if I'm wrong, but you've published 12 poetry books? | Transcription |

| 4:49 - 4:52 | Well ten poetry books. By next year, there'll be twelve. | Transcription |

| 4:52 - 4:57 | Yeah I'm sorry. Yeah you're right. By next year it will be twelve in ten years. | Transcription |

| 4:57 - 4:60 | Yeah. Well, is it ten? Yeah, I guess its ten, yeah. | Transcription |

| 4:60 - 5:01 | Ten in ten years. | Transcription |

| 5:01 - 5:04 | '94 was when the first book came out, right. Progeny of Air. | Transcription |

| 5:04 - 5:06 | And two books of fiction. And three books of nonfiction. Since 1994. | Transcription |

| 5:06 - 5:14 | Yeah, that's right. That's that sounds about right, yeah. That's pretty much it. Yeah, yeah, that's right. | Transcription |

| 5:14 - 5:23 | So... What's up with that? How is it, How do you, how many projects are you working on generally at the same time? | Transcription |

| 5:23 - 5:37 | Oh, God. I mean, you know, it's really weird because I hear this and it sounds very impressive. Whereas in my mental space I'm not successful. In my own mind I'm thinking, all the | Transcription |

| 5:37 - 5:44 | projects that I've really tried to bring through, the books I've written that haven't ever seen the light of day, the rejections, and so on. | Transcription |

| 5:44 - 5:55 | I mean, so it sounds, it's hilarious, because in my head, you know, I'm not thinking wow I've published all these books. In my head, I'm thinking, Man, you know, this book didn't get done, this book | Transcription |

| 5:55 - 6:07 | didn't, and so on and so forth. But I work on tons of projects at the same time. Because I'm fascinated about all these areas. I write about literature because I like writing about literature. I don't | Transcription |

| 6:07 - 6:16 | do it because it's part of my job. I do it because I'm passionate about it. And I write poems, because if I don't write poems regularly, I feel as if something is wrong with me. | Transcription |

| 6:16 - 6:32 | And I enjoy the process of organizing these things. Fiction is hard. I find fiction hard to write. But I've written, and in fact, I'm working on two novels now. And then I'm trying to learn how to | Transcription |

| 6:32 - 6:41 | write for children and so on. So I do a lot of stuff. And contrary to what people may think I get a lot of sleep. I really do. | Transcription |

| 6:42 - 6:46 | Cause you have, also you're teaching. You used to be in a band. | Transcription |

| 6:46 - 6:47 | Yeah I used to play in a band, yeah. | Transcription |

| 6:47 - 6:48 | You've produced 15 plays. | Transcription |

| 6:48 - 6:49 | Yeah, that's true. Yeah, | Transcription |

| 6:49 - 6:51 | And you have a family with three kids. | Transcription |

| 6:51 - 7:03 | I do have a family, yeah. That's my life, really, my family-- my wife and the three kids are my life. That's where I spend most of my time. But I think I work fast maybe. I write quickly. | Transcription |

| 7:04 - 7:17 | And I write-- I have no sort of circumscribed spaces where I can work or when I can work. I can work at any time. And I can work very intensely. | Transcription |

| 7:17 - 7:32 | Initially, it used to be, at least until the last two or three years, three years maybe, it used to be, I suspect, an anxiety that I need to get this stuff out before I lose it. Or before I die, you | Transcription |

| 7:32 - 7:40 | know, it was that kind of anxiety. But that's not driving me anymore. It's because of what I enjoy doing. And I like doing this kind of work. | Transcription |

| 7:40 - 7:56 | Yeah. It's handy. It's handy now. I mean, I'm not thinking of dying, for instance, which is helpful. Yeah, yeah. | Transcription |

| 7:57 - 8:11 | So, now in your experience working with music-- I was reading your biography. And there's a few things I had questions about, like, how has the guitar inflected your writing? | Transcription |

| 8:11 - 8:24 | That's an interesting question, I'm not sure. I wish I was a better guitarist. That's one thing I always wish. I wish I was a better musician. I never got music lessons growing up. I | Transcription |

| 8:24 - 8:26 | mean, it's a peculiar thing. My father was a musician. | Transcription |

| 8:27 - 8:37 | We didn't know this until I was in maybe my teens. I didn't know he was a jazz musician until I was in my teens when we ran into him, happened to be playing some piano. He took us somewhere. And he | Transcription |

| 8:37 - 8:46 | must have just gone in there and was fiddling with this piano, because we didn't have a piano in the house. And I, you know, we heard this man playing, you know, Monk, what is going on here? | Transcription |

| 8:46 - 8:47 | How old were you at the time? | Transcription |

| 8:47 - 8:57 | I was about 13, 14. This is the first I knew this man played the piano. And then of course, he told us, of course, he played with a jazz combo, you know, growing up in Jamaica, and so. | Transcription |

| 8:57 - 8:58 | And your father was a writer as well? | Transcription |

| 8:58 - 9:07 | Yeah and he was a writer as well, right. But we never took music lessons. You know, I mean, this man used to watch us trying to play pans and hitting boxes, and he would just walk by-- | Transcription |

| 9:07 - 9:17 | the man couldn't even think think, let me give them a lesson. You know what I'm saying? Let me just pay for somebody to just-- nothing, you know, they're having fun and so on. So I came to play the | Transcription |

| 9:17 - 9:27 | guitar. You know, in my teens in my late teens, and a friend of mine taught me a few chords. My wife who was my girlfriend at the time, she taught me some chords and so on. And she was she was very | Transcription |

| 9:27 - 9:29 | good and she had been trained as a musician. | Transcription |

| 9:30 - 9:41 | And I started jamming with a few chords. I started to write songs and so on. And my attitude is if I know some chords, I'm gonna write some songs. And so that part of that process was interesting, | Transcription |

| 9:41 - 9:45 | which when I started working with the band and writing songs for the band I wrote on the guitar. | Transcription |

| 9:45 - 9:58 | And I love that process, but I'm not sure what the connection might be. I mean, I think for me, it's what I like to listen to and I like to listen to folks like Dylan and of course, Marley and Paul | Transcription |

| 9:58 - 10:03 | Simon, and so a lot of guitar-driven songwriters. They fascinate me. | Transcription |

| 10:03 - 10:11 | And one thing that I've noticed often in your biographies is a reference to the first time you heard "Natty Dread". Could you tell us about that? | Transcription |

| 10:11 - 10:22 | Yeah, yeah. Yeah, "Natty Dread" is pivotal for many reasons. I mean, it's one of those poems in the sense that-- and of course, I've written a poem about it, because that works well, too. | Transcription |

| 10:22 - 10:35 | But it's-- my father, who was was a jazz musician, loved jazz, And so his thing was to listen to, I mean he loved Monk, Monk was the guy he listened to a lot in the house. And, but we knew he had I | Transcription |

| 10:35 - 10:36 | mean, he was a Pan-Africanist. | Transcription |

| 10:36 - 10:46 | My father grew up in Jamaica, was born in Nigeria, came to Jamaica when he was about two. His parents were missionaries in Nigeria, right, Black missionaries in Nigeria. And he came to Jamaica when he | Transcription |

| 10:46 - 10:55 | was two years old, went on to study at Oxford University, and then went to Ghana, which is where he was teaching and met my mother and so on. So that's where I was born. So he had a strong kind of | Transcription |

| 10:55 - 10:57 | Pan-Africanist sensibility, | Transcription |

| 10:57 - 11:08 | But he was also an Oxford man, you know, Oxford, so he was a very -- he'd speak with his Oxford accent. And so there's a really weird thing going on, because this was a sort of -- and Marxist, like, | Transcription |

| 11:08 - 11:20 | to the bone. I mean, my father was a hardcore Marxist. So, so I grew up in that space. And therefore, it made sense that he would be hooked into Marley, but it didn't make sense at a certain level, | Transcription |

| 11:20 - 11:21 | the connect wasn't there. | Transcription |

| 11:21 - 11:33 | Well, one day the man brings home a little sort of 45, you know, vinyl 45. And he plops it on, puts the thing on and it's Natty Dread, right? And he plays that over and over again, telling us to sit | Transcription |

| 11:33 - 11:42 | down and listen to it. And, you know, he's played it eight times and he says-- and then he takes it off and then he says, You need to pay attention to this. This is very important. And he goes back to | Transcription |

| 11:42 - 11:45 | his corner, reads his book and smokes a cigarette. | Transcription |

| 11:45 - 11:46 | And that was in when, 19-- | Transcription |

| 11:46 - 11:58 | This was in '75. This was in '75, Right? And that was I mean, that song, that song is a great song because you think that you know, Dread Natty Dreadlocks, right? And you know, Natty | Transcription |

| 11:58 - 12:10 | Dread is 5,000 miles away from home, don't care what the world says, and our children will never go astray, just like a bright and sunny day: we're going to have things our way. It's an anthem about | Transcription |

| 12:10 - 12:15 | the diaspora. It's an anthem about about the Middle Passage, and it's an anthem about survival. | Transcription |

| 12:15 - 12:26 | And he got it about Marley, then. Before Marley was huge, or anything, and he was telling us pay attention to this guy. And I never stopped paying attention to Marley after that. | Transcription |

| 12:27 - 12:30 | Really that influenced your... obviously you've written books about Marley.[Inaudible] | Transcription |

| 12:30 - 12:40 | Yeah, I've written about Marley. Yeah. I've written about reggae. Yeah, because reggae is-- the 1970s is when I grew up, you know, I grew up in the '70s, Jamaica. This was the period | Transcription |

| 12:40 - 12:52 | where there was incredible political tension going on. This is the fear when Michael Manley was the Prime Minister experimenting with socialism, having strong relationships with Cuba, right. And at | Transcription |

| 12:52 - 12:60 | the same time, making connections with Africa, which prior to that Jamaicans were not necessarily interested in, right, because there's the whole colonial attitude to Africa. | Transcription |

| 12:60 - 13:10 | So in the 70s, Samora Machel comes to Jamaica, Nyerere comes to Jamaica, I mean everybody's coming to Jamaica, so Africa has a presence. My father, who was working at the Institute of Jamaica starts | Transcription |

| 13:10 - 13:22 | this thing called the African Caribbean Institute. So there's all this cross pollination, and there's-- beauty queens get darker and darker, you know, all kinds of things are happening in this very | Transcription |

| 13:22 - 13:23 | volatile world. | Transcription |

| 13:23 - 13:36 | Because in '76, we get political elections going on with tremendous violence in '80 a lot of violence going on. And in the cauldron of all of this energy, reggae emerges, like an explosion! I mean, | Transcription |

| 13:36 - 13:48 | Bob Marley, Bunny Wailer, Burning Spear, Peter Tosh, you know, Culture, The Gladiators, and song group after song group, hitting the world and really transforming it. And I'm sitting in the middle of | Transcription |

| 13:48 - 13:54 | that, How the hell can that not be my literary and my aesthetic kind of foundation. | Transcription |

| 13:54 - 14:07 | So reggae becomes an aesthetic framework out of which I think my work emerges, and it shapes and directs that work and helps me to interpret not only the work of the '70s and the '80s, but the work | Transcription |

| 14:07 - 14:19 | prior to that. Because it becomes a prism through which one begins to understand the literary practice of Africans in the diaspora, a practice that comes out of radical action, revolution, resistance, | Transcription |

| 14:20 - 14:28 | and mixing that with religion, and sex, and rhythm, and all of that. And that's all contained in reggae music. | Transcription |

| 14:28 - 14:39 | Well, how would you say, I guess I would say the Afro-Caribbean literary tradition, has affected the African American literary tradition and vice versa? | Transcription |

| 14:39 - 14:49 | Well, you're asking the wrong person because, you know, I'm from Jamaica, and basically, we invented everything. For instance, Adam and Eve really started in Jamaica. I mean, most people | Transcription |

| 14:49 - 14:60 | don't know this, right? I mean, that's like the beginning of all things, right? And so I may be hyperbolic in some of the things I might say, but just a tad, just a smidgen. But there's a great | Transcription |

| 14:60 - 15:09 | influence. I mean, I mean, let's be real though. You know, people talk about Bob Marley now, and everybody knows Bob Marley. Look in the '70s African Americans were not listening to Bob Marley. | Transcription |

| 15:09 - 15:20 | I mean, Bob Marley-- the people who were following Bob Marley were white college students. Simple as that. And the reason why African Americans were not so deeply ingrained into Bob Marley as they | Transcription |

| 15:20 - 15:32 | might be now was because there was an African American music tradition happening, that was doing the job that it needed to do. I mean, this is Marvin Gaye style. This is Stevie Wonder. This is when | Transcription |

| 15:32 - 15:36 | these political voices are emerging in the music, right? This is the Funkadelic this is-- | Transcription |

| 15:36 - 15:47 | Something is going on here that is quite revolutionary and radical, which is influencing Jamaica. But when you get to the late '70s, you begin to see the connection taking place. And there is no | Transcription |

| 15:47 - 15:60 | accident that hip hop emerges, right, in the in the late '70s, early '80s. Because that's dancehall music, and it's influenced. Many of the dancehall musicians would migrate to New York, and were part | Transcription |

| 15:60 - 16:04 | of the Bronx scene, parts of the Brooklyn scene and influencing the hip hop. | Transcription |

| 16:04 - 16:15 | And that is very much a part of that, that shapes it. And intellectually, I mean Stokely Carmichael, right? I mean, a number of important-- think, Michael Thelwell, all of these guys coming out of the | Transcription |

| 16:15 - 16:26 | Caribbean and having an impact on Black Arts Movement, having an impact on Black issues, and Black political issues. All of that is going on at the same time. | Transcription |

| 16:26 - 16:37 | So there are these interesting and fascinating connections. I mean, one of the things people don't know is Amiri Baraka has-- one of his early chapbooks in the early '70s, maybe mid '70s is a reggae | Transcription |

| 16:37 - 16:42 | chapbook. See, people don't know that. Even Baraka was a reggae man. | Transcription |

| 16:44 - 16:57 | So yeah. And he got it. It's called something like 'reggae regatta' or something, right? Yeah, it's a little-- somebody found it at a flea market and brought it to me and I thought, wow! I mean, I | Transcription |

| 16:57 - 17:07 | have a cherished thing, I don't think many people have this thing. But I have it in my, you know, I have it at home. Right? So there is an influence. I think that influence is there because the | Transcription |

| 17:07 - 17:11 | connection makes sense. It's the shared history, right? | Transcription |

| 17:11 - 17:21 | But there is a difference, right? The histories are different. We, you know, in Jamaica, you grew up Black, you're you know, 80 percent to 90 percent of the population, that's different. The political | Transcription |

| 17:21 - 17:32 | dynamics are different than if you grew up Black, say in Mississippi. If you grew up Black in South Carolina, now, you're 40 percent, which is high. But it's not nothing like, you know, being 90 | Transcription |

| 17:32 - 17:38 | percent of the population. And anywhere else in America, you're down to, you know, 20 and 30 percent. That's where you're falling in. | Transcription |

| 17:38 - 17:49 | When that happens, the idea of the relationship between the sort of dominant, mainstream culture becomes quite different. And the politics of that are quite, quite different. | Transcription |

| 17:49 - 17:52 | So you've been living in the States, United States since... | Transcription |

| 17:52 - 17:53 | Since '92. Yes. | Transcription |

| 17:53 - 17:56 | '92. You went to the University of Southern Ca-- South Carolina. | Transcription |

| 17:56 - 17:58 | South Carolina. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. | Transcription |

| 17:58 - 18:03 | So how did you your perspective change in terms of literature? Did your perspective change at all when you came? | Transcription |

| 18:04 - 18:14 | Um, no, not it didn't change. I mean, I began to read more, but I mean I was reading African American literature from-- you know, as Bob Marley would say, from ever since. Listen, I mean, | Transcription |

| 18:14 - 18:27 | you know, like the poster girl for me growing up in the '70s was Angela Davis. I mean, we had her poster with that fro. And she's fine. I mean there was all of that going on. I was into that. I mean, | Transcription |

| 18:28 - 18:33 | focusing and realizing the issue of Black struggle, I mean, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and so on. | Transcription |

| 18:33 - 18:46 | We had all those books, all that information at home growing up with it. So as is typical, remember, this United States is a powerhouse of a nation, and Americans will know less about the world than | Transcription |

| 18:46 - 18:57 | the world knows about America. And that's just the reality of it. So I didn't come into America ignorant. I didn't come to South Carolina ignorant, but I came with biases. I came with perceptions that | Transcription |

| 18:57 - 19:04 | came out of media that came out of things I might have read and so on. For instance, I thought I knew what grits was, apparently I didn't. | Transcription |

| 19:06 - 19:19 | Didn't know it was porridge. Turns out it's porridge. And I don't like porridge. So I thought I would like grits, right? That didn't work out so well. But so there are a lot of things I didn't really | Transcription |

| 19:19 - 19:23 | understand, and the dynamics of race and the South I didn't really understand until coming here. | Transcription |

| 19:24 - 19:31 | But I've moved around a lot. I've lived in England, lived in Ghana, lived in Jamaica, lived in a few places. And one of the things that-- I lived in Canada for a number of years-- so one of the things | Transcription |

| 19:31 - 19:42 | that I always learned was wherever I am, I am going to create my art out of that space and out of the community that I connect with there. | Transcription |

| 19:42 - 19:54 | And very quickly, one of the first things I did when I went to Sumpter, which was a small town in South Carolina, was to go to the Black, the African American community center, work with them, meet | Transcription |

| 19:54 - 20:04 | the elders in the community. I interviewed the women especially as a way to learn more about them, but as a way for them to welcome me and teach me something about that community. | Transcription |

| 20:05 - 20:16 | And that made a tremendous difference in my understanding of who I am. My understanding of what place I have and what connection I have to that place itself. And a lot of my work comes out of that | Transcription |

| 20:16 - 20:18 | connection and that dialogue. Yeah. | Transcription |

| 20:19 - 20:26 | Well, how do you think-- Do you think your poetry has influenced other poets? Or how do you think--? | Transcription |

| 20:27 - 20:36 | I don't know. I'm always surprised when people come and tell me they've read my book. I mean, that shocks me. I mean, and one of the things that Cave Canem has done for me is that, you | Transcription |

| 20:36 - 20:48 | know, like I'm about a read a poem and then people clap like they know the poem. That's, that's new, that's fresh. That just happened, Right? You know, and that's, that's been interesting. I work with | Transcription |

| 20:48 - 20:54 | a lot of writers, I work with a whole lot of writers. I mean, you think a lot of my time is spent writing, no. | Transcription |

| 20:54 - 21:06 | Most of my time is spent reading other people's work, writing blurbs, writing analyses of it, helping people with their-- and this is writers from major published writers to writers who are just | Transcription |

| 21:06 - 21:15 | starting out. I do a lot of work with people, read a lot of material. I try not to impose my style, or whatever it is, on them. | Transcription |

| 21:15 - 21:29 | But I hope that I'm teaching them to create a sensibility that will help them to enhance their work. And as for influence, who knows. I mean, that will work out itself later. And I don't want too many | Transcription |

| 21:29 - 21:35 | people to write like me, because that takes away my opportunities. We can't have that. | Transcription |

| 21:40 - 21:54 | How do you think, since the last Furious Flower happened ten years ago. And it was a watershed event in the African American literary community. How do you think that community has | Transcription |

| 21:54 - 21:60 | changed in that ten years? And do you foresee any changes in the next five to ten years? | Transcription |

| 21:60 - 22:11 | There are huge changes. And the changes come from-- Look, one of the interesting things about our art and about the politics and the shaping of the perception of that art is that often, | Transcription |

| 22:11 - 22:24 | if you don't create movements that can give it a profile, what happens is that the art continues without any kind of focal attention to it. It is artificial in many ways, when we declare a movement | Transcription |

| 22:24 - 22:31 | when we declare that there's this new sort of school of writing and all that. It is artificial, and it's calculated, right? | Transcription |

| 22:31 - 22:41 | And it's done again and again. And it's done to give attention to what is happening in the work. But it's also done to give it a point of reference. Now what happened with Furious Flower one, I think, | Transcription |

| 22:41 - 22:51 | is that it brought so many voices together and said, look at what we are doing and look at what we've become. And Furious Flower two is looking at a movement. And that particular moment, of course, is | Transcription |

| 22:51 - 22:58 | the Black Arts Movement which is really a kind of focal point. But that is a credible and a clearly defined movement, you see. | Transcription |

| 22:59 - 23:11 | What is happening today is to me even more fascinating. And it's fascinating because I think there are so many writers writing, but it is also a true reflection of what is happening in America in | Transcription |

| 23:11 - 23:26 | defining African American-- the nature of African American resistance, and African American action today. You can't use the model of the of the '60s, because the landscape has changed. But you can | Transcription |

| 23:26 - 23:33 | draw from the model of the '60s. But then you have to have a redefinition of your new model and how you're going to deal with it. | Transcription |

| 23:33 - 23:43 | Because you see, you're not dealing with with Motown now. What you're dealing with, you're dealing with hip hop now. And now hip hop is a very complicated thing, right? And what we haven't done yet | Transcription |

| 23:43 - 23:50 | enough of, and I'm noticing that people are starting to deal with it, is to really try and get what is happening with hip hop. | Transcription |

| 23:50 - 24:02 | How do you mix the materialistic element of it-- which is the bling-bling, the money-- with the idea of resistance? How do you rationalize that? How do you impose or how do you introduce ideas of | Transcription |

| 24:02 - 24:13 | signify in the midst of that pressure, right? Those elements become important. Now, when you have a Rita Dove and a Yusef Komunyakaa and all of these names who are big names, and are recognized as big | Transcription |

| 24:13 - 24:22 | poetic names, and they get all the major awards and so on, it changes the landscape, in the sense of what you can say about attention we're getting and all those kinds of things. | Transcription |

| 24:23 - 24:35 | So I think the challenge for today's poet is to say, what is this world I'm living in now? What is the thing-- what are the things that affect our community? And what is the language that we are going | Transcription |

| 24:35 - 24:46 | to use today to speak to that community. Right? And that, to me, is the biggest challenge that faces many writers. The opportunities are there, but I don't know if we're grappling with that as much. | Transcription |

| 24:46 - 24:57 | And I see that the Furious Flower gives people a chance to look at it, to see where it's coming from, but hopefully to start asking, what is our voice saying now? And I think the closest thing that | Transcription |

| 24:57 - 25:08 | comes to doing that is Cave Canem. I really think that. And it is the one entity that brings all these African American poets together and forces them to ask themselves questions about what they're | Transcription |

| 25:08 - 25:21 | doing. It's the one entity that's doing that about now. Not about then, but about now, Right? And it's very interesting what happens in that in that space. Very, very interesting. Yeah. | Transcription |

| 25:24 - 25:38 | Gwendolyn Brooks said, 'We are each other's/ harvest: We are each other's/ business: We are each other's/ magnitude and bond.' In the next 10 years, do you... What I see when you talk | Transcription |

| 25:38 - 25:45 | about Cave Canem is, I guess a real manifestation of that thought. | Transcription |

| 25:45 - 25:45 | Yeah. | Transcription |

| 25:45 - 25:60 | Right? I mean, do you foresee perhaps more collectives occurring like Cave Canem, or more organizations such as Cave Canem happening perhaps not, if not in the United States perhaps in | Transcription |

| 25:60 - 26:01 | other parts of the world? | Transcription |

| 26:01 - 26:11 | Yeah, yeah. Cave Canem is a good model and its work-- I mean we've taken from Cave Canem to do work in Jamaica with the Calabash Writer's Festival, plus the writer's workshops that we do | Transcription |

| 26:11 - 26:21 | there and so on. And we are publishing work by writers now. We've seen work that came out of those workshops that we published here in the States and so on. Cave Canem is a very effective model. The | Transcription |

| 26:21 - 26:26 | idea is what you're saying is that-- and remember we're not dealing with a minority group in Jamaica, right? | Transcription |

| 26:26 - 26:41 | But we're saying: Let's bring a nurturing space for writers to come together and to treat their work with respect, but with a hard-edged integrity, about quality, and about craft. And that's | Transcription |

| 26:41 - 26:52 | important, that is really important. It's the challenge. It's to challenge the easy path. It's to say, if you get up and you say something, and you say, revolution, do you know what the heck you're | Transcription |

| 26:53 - 26:53 | talking about? | Transcription |

| 26:53 - 27:03 | Do you know what that means? Do you understand the implications of that? Or is it a good word that rhymes with absolution? I mean, you know, are you you know, do you understand what is going on in the | Transcription |

| 27:03 - 27:14 | midst of that. And so Cave Canem offers that model, but that model can be replicated all through, right? And in the work I do, I started something called a South Carolina Poetry Initiative. Now, | Transcription |

| 27:14 - 27:27 | that's not something for African American writers. But there's something about creating an institution as a Black person in South Carolina, that assures Black writers that this space is welcome to me. | Transcription |

| 27:28 - 27:37 | And so what these people in South Carolina suddenly see is that so many poets are coming to the events that we have, the collaborations that we have, and are responding to it, and they're people of | Transcription |

| 27:37 - 27:50 | all races, and coming together around the idea of poetry. Right? So I think that what we are looking for in the future is true, the spirit of Cave Canem is very important. But at the same time it is | Transcription |

| 27:50 - 27:54 | to get people in institutions that really have an impact. | Transcription |

| 27:54 - 28:08 | For instance, there are so few people, African Americans, in publishing. Period. They're not there. So what do we end up doing? We create, you know, we don't have people in the positions to look at | Transcription |

| 28:08 - 28:17 | the work that is emerging, and that is coming on? Well, what that means is that we got to get people involved in publishing. Get them involved in that field, that area, even if it's to create a new | Transcription |

| 28:17 - 28:23 | press, but know that you're coming out of a kind of clear understanding of what is happening. | Transcription |

| 28:24 - 28:26 | The only press I can think of is Third World Press. | Transcription |

| 28:26 - 28:28 | Third World Press. Yeah, right. | Transcription |

| 28:29 - 28:32 | The Third World Press would probably be the major [inaudible]. | Transcription |

| 28:32 - 28:43 | Third World Press is the major press, but, and Third World Press is a is a Black-owned press and so on. But if you go to other presses, you won't find a Black person working there. That's | Transcription |

| 28:43 - 28:53 | what I'm saying. Right? And these are all major presses. Right? We don't find enough, especially for poetry, right? And we want to see more people in those kinds of positions. Because you know how | Transcription |

| 28:53 - 28:57 | this thing goes, I'm sorry. Like it's who knows who. | Transcription |

| 28:57 - 29:05 | You know, I mean we like to think it's the quality of the work and so on and so forth. Yeah, we work that out. But a lot of quality work is out there that doesn't get any attention. And it's because | Transcription |

| 29:05 - 29:13 | somebody sat in there and said, you know, I saw this person and I really like their work, and let's make it happen. A lot of it works that way. Right? | Transcription |

| 29:13 - 29:23 | You know I was watching everybody at this event, and so-- which was great, and I said, I remembered-- I said, the person who is here who hasn't published a book, really has got a manuscript of poems | Transcription |

| 29:23 - 29:33 | that they really want to get out and they're watching all these people. And I said, I know that some of them are sitting there saying, gosh, will I ever get there. You know? Who am I in the midst of | Transcription |

| 29:33 - 29:45 | all of this? You know, will I ever be on the bill, right? Now I've just got to do the open mic, you know, will I ever get a break? And I knew that feeling because I've been in that place, right? | Transcription |

| 29:46 - 29:57 | Even here in the States. I had published three books of poems. But if I came to a Black African American conference, nobody would know who I was. Because my books were published in England. Right? And | Transcription |

| 29:57 - 30:10 | nobody knows who you are if your books are published in England, in America. That's just the way it is, right? But what I say to them is No, think about why you're working. Come back to why you're | Transcription |

| 30:10 - 30:17 | working, why you have the passion for your work, and let that be the driving force and the motivation to say, I'm going to stick to it. | Transcription |

| 30:17 - 30:28 | And that all these people who are sitting up there, your big writers, and so on so forth? Every one of them has their anxieties about their status, right? Because even though you know, like you look | Transcription |

| 30:28 - 30:38 | at me and say you published 10 books of poems, I say, Well, yeah. But I'm looking at somebody else and I'm thinking, gosh, now this guy has it made you know? Well it's all nonsense, right? Because the | Transcription |

| 30:38 - 30:40 | grass is always navyer, right? | Transcription |

| 30:40 - 30:52 | So the key thing is then you focus on what you're doing, and what your work is doing and what it does about articulating your experience. But what you are doing about honing and disciplining yourself | Transcription |

| 30:52 - 30:56 | in the craft, and making it happen, and to me that that becomes the most important thing. | Transcription |

| 30:58 - 31:01 | I think that's a good note to end on. Thank you so much. | Transcription |

| 31:01 - 31:04 | Hey, you're welcome. Good. | Transcription |

| 31:04 - 31:12 | Um, don't leave yet. We just want to get some [inaudible] shots. If you could just chat [inaudible] just don't talk at the same time. | Transcription |

| 31:17 - 31:29 | You've been doing the talking. That's great. I, I see that Cave Canem is... I think people come to Cave Canem and they're very skeptical. | Transcription |

| 31:29 - 31:30 | Yeah, yeah. | Transcription |

| 31:30 - 31:31 | And they should be. | Transcription |

| 31:31 - 31:39 | They should be. I really believe in skepticism, by the way. I believe in healthy skepticism. I believe in coming to conferences like this and in some sessions going, "Oh man". | Transcription |

| 31:39 - 31:40 | Yeah, right. | Transcription |

| 31:42 - 31:45 | It's good! We have to do that. Let's not get precious about it. | Transcription |

| 31:47 - 32:04 | Like your graduation it's-- | Transcription |

| 0:06 - 0:11 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 0:13 - 0:20 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 0:24 - 0:36 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 0:37 - 0:49 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 2:02 - 2:03 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 2:03 - 2:14 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 3:39 - 3:39 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 3:40 - 3:41 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 3:46 - 3:52 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 3:52 - 4:04 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 4:40 - 4:49 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 4:49 - 4:52 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 4:52 - 4:57 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 4:57 - 4:60 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 4:60 - 5:01 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 5:01 - 5:04 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 5:04 - 5:06 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 5:06 - 5:14 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 5:13 - 5:23 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 5:23 - 5:37 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 6:42 - 6:46 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 6:46 - 6:47 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 6:47 - 6:48 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 6:48 - 6:49 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 6:49 - 6:51 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 6:50 - 7:03 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 7:57 - 8:11 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 8:11 - 8:24 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 8:46 - 8:47 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 8:46 - 8:57 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 8:57 - 8:58 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 8:58 - 9:07 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 10:03 - 10:11 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 10:11 - 10:22 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 11:45 - 11:46 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 11:46 - 11:58 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 12:27 - 12:30 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 12:30 - 12:40 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 14:28 - 14:39 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 14:39 - 14:49 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 17:49 - 17:52 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 17:52 - 17:53 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 17:53 - 17:56 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 17:56 - 17:58 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 17:58 - 18:03 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 18:04 - 18:14 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 20:18 - 20:26 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 20:27 - 20:36 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 21:40 - 21:54 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 21:60 - 22:11 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 25:24 - 25:38 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 25:45 - 25:45 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 25:45 - 25:60 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 26:01 - 26:11 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 28:24 - 28:26 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 28:26 - 28:28 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 28:29 - 28:32 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 28:31 - 28:43 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 30:58 - 31:01 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 31:01 - 31:04 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 31:03 - 31:12 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 31:17 - 31:29 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 31:29 - 31:30 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 31:30 - 31:31 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 31:31 - 31:39 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 31:39 - 31:40 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |

| 31:42 - 31:45 | Kwame Dawes | Speaker |

| 31:47 - 32:04 | Tyehimba Jess | Speaker |