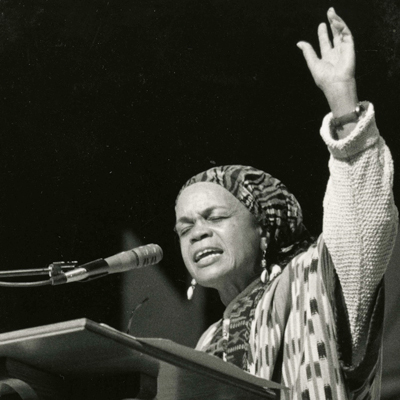

Sonia Sanchez

Sonia Sanchez is a poet, playwright, educator, storyteller, womanist, and revolutionary. She has a voice that bridges generations. She was instrumental in the Black Arts Movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s, and has continued to publish impactful, widely influential works of poetry ever since. She has visited hundreds of colleges and universities to teach and spread her poetry and philosophy, and traveled to many countries to read with the same mission. As she notes concerning a poet's role, ”above all what we do is try to keep us human.”[1]

In her long and prolific career, Sanchez has reforged poetic forms such as the haiku and tanka to better fit her calls of and for radical love. She has bridged the gap between personal and political art forms, blurring the line between self-discovery, political activism, and spiritual teaching. Dr. Joanne Gabbin has referred to Sonia Sanchez’s message as “one of redeeming realism” and “gemlike intensity”.[2]

Sanchez’s groundbreaking application of jazz improvisation techniques and everyday language in her collection We a BaddDDD People opened new possibilities of musical and linguistic fusion in spoken word poetry and rap. In her revolutionary womanism, Sanchez also explores the many varied connections and disconnections between love and sexuality. She lets the joy of their union and the pain of their disjunction show through the experimental forms in collections such as I’ve Been a Woman and Homegirls and Handgrenades.

Among the many honors she has received are The Lucretia Mott Award, The Langston Hughes Poetry Award, and The Leeway Foundation Transformational Award, to note only a few. Most recently, she has won the $250,000 Gish Prize for pushing the boundaries of poetic form, for her contributions to social change, and for her fearless truth-telling.

In this interview with Dr. Joanne V. Gabbin, Sonia Sanchez discusses how Black poetry and literature transformed the dominant narratives in academia, the U.S., and the world, emphasizes the importance of global solidarity, and demonstrates the power that poetry has to educate, inspire, and counter misrepresentation in politics and the media.

More information:

Interviews:

Interview with Susan Kelly. Sonya discusses the literary culture of Harlem in the ‘60s, her involvement with the Nation of Islam, how she conducted the first college course on African American Women’s Literature, and what it took to resist and combat attempts to erase the historical events, Black poetry, literature, and political philosophy of the ‘60s, ‘70s, and beyond.

Interview with Christina Knight. Discuss Sanchez’s ancestral influences, Sanchez confronting racism in academia, the job market, and the libraries in her time as a student.

Interview with India Dennis-Mahmood. Sanchez and Dennis-Mahmood touch on the history of these feminisms, the struggles and influence of Black students on predominantly white campuses, and how theorists of modernism are often dishonest about its origins in the art of the African Diaspora.

Video Interview, with Major Jackson. Touches on Sanchez's childhood, her writing process, her acquaintance by Amiri Baraka, and the love of teaching.

Essays:

”The Poet as a Creator of Social Values”: Essay written by Sanchez in the ‘80s. She discusses the history of poetic language from its early forms to its racist distortion by white settlers, to the resistance and reclamation poets in the African Diaspora have effected.

”Sonia Sanchez: The Will and the Spirit”: Essay on Sanchez’s work, and an interview with D.H. Melhem covering Sanchez’s childhood practice of poetry writing, her musical influences, and the performance of poems.

”Black Magic Woman: Sonia Sanchez and her Work”: Essay from the early ‘70s discussing the multiple directions that Sanchez’s impact on the Black Arts Movement were taking. Contains several excerpts of Sanchez’s contemporary poems, with analyses.

Poems and readings:

Selection includes several haikus, among other poems.

Selection contains an excellent tracing of Sanchez’s style as it transforms across her publications. Also includes selected poems.

Other:

Sanchez’s website including biographical info, books and CDs, and contact information.

[1]:Gaither, Larvester. "Part II - Interview with Sonia Sanchez." The Gaither Reporter 3, no. 6 (Jul 30, 1996): 49.

[2]:Gabbin, Joanne Veal. "The Southern Imagination of Sonia Sanchez." In Southern Women Writers: The New Generation, edited by Tonette Bond Inge, 180-202. The University of Alabama Press, 1990.

Preferred Citation:

Sonia Sanchez Interview, 9/25/2004 (FF143). Transcribed and edited by Evan Sizemore, 2021-2022, part of the Mellon-funded AudiAnnotate Audiovisual Extensible Workflow Project. Based on video recordings made by WVPT to document the second Furious Flower Poetry Center decennial meeting, September 23-25, 2004. Part of the Furious Flower Poetry Center Conference Records, 1970-2015, UA 0018, Special Collections, Carrier Library, James Madison University Libraries, Harrisonburg, Virginia, media file FF143. Collection finding aid: https://aspace.lib.jmu.edu/repositories/4/resources/487.

Browser Directions:

Audio and video playback is activated by the timestamped annotation section you click in. Search field will find any word or phrase in the Transcription, Speaker or Environment annotation layers. Annotation layers can be ordered by Time (default), Annotation contents or Annotation layer labels by selecting the up/down arrows on the right. Speaker and Transcription layers are matching color-coded to facilitate reading.

| Time | Annotation | Layer |

|---|---|---|

| 20:25 - 20:26 | [sigh] | Environment |

| 22:20 - 22:28 | [Sonia Sanchez singing] | Environment |

| 27:28 - 27:29 | [Sigh] | Environment |

| 27:30 - 27:50 | [Crying] | Environment |

| 27:53 - 27:53 | [sniffle] | Environment |

| 28:28 - 28:29 | [laughs] | Environment |

| 30:09 - 30:25 | [A/V cuts out] | Environment |

| 0:01 - 0:08 | S-a-n-c-h-e-z, James Madison University, September 25, '04. | Transcription |

| 0:12 - 0:27 | Sonia, Gwen said in one of her poems, 'This is the urgency; Live!/ and conduct your blooming in the noise of the whirlwind.' I know because of our long association, that it has not | Transcription |

| 0:27 - 0:38 | always been easy to be a black poet in the second half of the 20th century, or the first decade of the 21st century. | Transcription |

| 0:38 - 0:45 | Could you talk about that a little bit? How have there been those difficulties? | Transcription |

| 0:45 - 0:55 | Well, you know, I think that it's been difficult, you know, all the years that we've been here in this place called America, being writers, or even poets, because you do know that | Transcription |

| 0:55 - 1:06 | teaching in the English department, they really didn't think that we belonged there, because it is called 'English Department'. However, we did go there, and we did make somewhat of a [inaudible] | Transcription |

| 1:06 - 1:07 | splash. | Transcription |

| 1:07 - 1:19 | But also what you know-- reading early literature, you understood finally, how difficult it was for DuBois, how difficult it was for Phyllis Wheatley, how difficult it was for Delaney and all those | Transcription |

| 1:19 - 1:31 | people, Zora, to write and to be accepted as writers in this whole interesting thing called writing in America-- what they call the canon, the literary canon. | Transcription |

| 1:32 - 1:44 | And quite often we ourselves are not even accepted into that canon, at this stage of the game, after all of these years of really what I call invigorating this thing called American writing. That's | Transcription |

| 1:44 - 1:47 | what we've done. We have invigorated and stretched it. | Transcription |

| 1:47 - 2:03 | When you began to include Black writing, in, in this writing, then it opened up to Native American writers, it opened up to Jewish writers. I mean, within the genre, it opened up to Asian writing, | Transcription |

| 2:03 - 2:15 | Women's writing, you know, Lesbian Studies, Gay Studies. And what it did is it spread all out and said, simply, you know, here we is, you know, it is not all about European writing. | Transcription |

| 2:15 - 2:29 | And that made for such an interesting way of looking at the world, and looking at literature. I mean, you had, you have this very wonderful literature that goes on and says, you've got to look at | Transcription |

| 2:29 - 2:39 | something called Westward Expansion with a different eye, you know, than saying, by golly, by gee, we were just going out west to expand, no, you also killed a whole lot of people, you know, doing | Transcription |

| 2:39 - 2:40 | that also, too. | Transcription |

| 2:40 - 2:51 | So all that was necessary. So it meant that you had to look at the words of the Native Americans, you know, you had to understand that this was not just them, chanting, going 'Ooga booga booga', like | Transcription |

| 2:51 - 3:04 | African writing, you know, or going 'Aayayah-wuhwuhwuh' but listen, and we did that we brought that within that arena. And I remember once reading in the Midwest, and a Native American person came up | Transcription |

| 3:04 - 3:09 | to me and said, ah, sister Sanchez, when you chanted, I heard my people. | Transcription |

| 3:10 - 3:21 | And I remember leaning back, I leaned back on my own breath, and felt his breath and knew the connection. Which was so important to us, because at first, you were so interested in bringing just the | Transcription |

| 3:21 - 3:26 | word of the African American writing, that you didn't always hear other people breathing around you. | Transcription |

| 3:26 - 3:37 | But once you were able to firm yourself and look out at the world, at the diaspora, you heard other breaths, you smelled other breaths, you heard other chants, you say, this is the same chant. These | Transcription |

| 3:37 - 3:42 | are the same words. And these are the same kind of things that are happening. | Transcription |

| 3:42 - 3:53 | When I went to China in '73 we were in Hong Kong waiting for a train. And this Chinese man came darting across the-- we were the first group, after Nixon had climbed the Great Wall of China, and so we | Transcription |

| 3:53 - 4:06 | had people like Candice Bergen and Alice Childress, and, you know, all kinds of people going there, the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the people who had been white-listed, you know, in America at | Transcription |

| 4:06 - 4:09 | McCarthy, those writers were on that trip. | Transcription |

| 4:09 - 4:22 | And this Chinese man came running across the, the train station, crazy in ragged clothes. Everybody jumped, and I stood and said how you doing, brother? Because see, I've seen you in Harlem, you know, | Transcription |

| 4:22 - 4:33 | I've seen you in Chicago. I've seen you in Alabama. Hello, how you doing? You know. So it's the same, and you begin to understand that, then you understand your literature more, and you understand the | Transcription |

| 4:33 - 4:35 | world's literature more, also too. | Transcription |

| 4:35 - 4:48 | Writing out of this frenetic chaos that we are so used to. A young woman stood up yesterday in the conference and talked about being from Pakistan and how we have to make a | Transcription |

| 4:48 - 4:58 | connection with the women in Pakistan because our experiences as women in this country are similar to those that she experienced growing up there. | Transcription |

| 4:58 - 5:12 | And I thought about the theme of the conference, at least the sub-theme, 'Cross Pollination in the Diaspora', because we have to understand that our poetry has stretched far beyond our boundaries, and | Transcription |

| 5:13 - 5:24 | has impacted many, many people. And I know that your poetry has done that, because you are affectionately called the poet of the universe. And why do you think people call you that? | Transcription |

| 5:25 - 5:36 | I don't know, but the point is that I think we have learned, you know, that we all have the same voice, as I said before. When I was in China in '73, and I was reading my poetry at | Transcription |

| 5:36 - 5:44 | University of Beijing, one of the professors stood up and said, 'Ah, professor Sanchez. We understand this really well', they said, | Transcription |

| 5:45 - 5:57 | What you said... we've been in Shanghai, and he said, you know, and you're talking about your black experience, he said, but you know, here in China, they had signs in Shanghai that said, 'no Chinese | Transcription |

| 5:57 - 6:07 | or dogs allowed'. So what you do is that you understood, it was indeed-- that oppression, against people of color was a real oppression all over the world. | Transcription |

| 6:07 - 6:17 | And so when we began to write what we wrote, at some point initially we thought, this is just this experience, this is just my pain. And I had to tell people, by golly, by gee, this is all our pain, | Transcription |

| 6:17 - 6:30 | you know, here, and you know, all of it. So therefore, the greatest thing I think that happened to me, and probably to you and a lot of us in this field, is that we taught, you know, and in teaching-- | Transcription |

| 6:31 - 6:35 | I always say to people, teaching makes you-- writing and teaching will keep you human. | Transcription |

| 6:35 - 6:48 | You know, because you will be in a classroom-- I remember teaching at Temple University up at the, up the art campus, and this young white man walked in with his hair all dyed, and he very obviously | Transcription |

| 6:48 - 6:53 | was gay. And I was in my classes, you know, in a circle, and nobody wanted to grab his hand. | Transcription |

| 6:53 - 7:04 | So I grabbed his hand and told this young woman 'you grab his hand', you know, and I held on very tightly, and I said, you're in this circle, you know, everyone's in this circle. And he was such a | Transcription |

| 7:04 - 7:08 | great writer, that by the third week, everybody wanted to hold his hand. | Transcription |

| 7:08 - 7:21 | So it is important for us as writers, you see-- I did a long essay, "The Poet as Creator of Social Values". We who create these things, we who say and set the tone for history-- when 9/11 happened, | Transcription |

| 7:21 - 7:33 | where did they go? They didn't go to the diplomats, they went to the poets, and say help us understand this tragedy, help us to understand what has happened, help us to breathe, because we're not | Transcription |

| 7:33 - 7:35 | breathing, now, in this particular place, help us to live. | Transcription |

| 7:35 - 7:47 | And writers and poets have always helped people to live. And the question that must be answered here in the 21st century is that-- What does it mean to be human? If, if we don't answer that question, | Transcription |

| 7:47 - 7:56 | we're all doomed. You know, this is like, this is not like, what does it mean to be human if you're Black, or if you're Puerto Rican, or if you're Asian, or if you're gay, or if you're Jewish, or if | Transcription |

| 7:56 - 7:57 | you're Muslim or whatever? | Transcription |

| 7:57 - 8:06 | No, what does it mean to be human on this earth? Because if you don't answer it, this Earth is gonna swallow us whole and say I'll wait billions of years for some more of you to come out of the sea. I | Transcription |

| 8:06 - 8:18 | mean, this is serious business going on right now at this particular time. So I say to my students all over, we've got to begin to answer this question in a very real concerted effort, you know, no | Transcription |

| 8:18 - 8:23 | half-sliding here, no half-stepping here at all, these are serious times. Period. | Transcription |

| 8:24 - 8:33 | You have to remember that, when you taught that year at Lincoln University, it must have been 1975. | Transcription |

| 8:33 - 8:37 | Sure was. Ooh. I was teach-- | Transcription |

| 8:37 - 8:38 | Oh, no maybe, maybe it was later. | Transcription |

| 8:38 - 8:38 | Later, | Transcription |

| 8:38 - 8:38 | It was 19-- | Transcription |

| 8:38 - 8:40 | no it was about '77, or '78. | Transcription |

| 8:40 - 8:51 | Yes, yes, you came in then. I remember coming to your class, and you did the ritual of holding hands at the end of the class, and having-- | Transcription |

| 8:51 - 8:52 | Yeah, making a circle. | Transcription |

| 8:52 - 9:08 | Making a circle and having the students say something supportive, something positive about someone in the class, and I picked up that ritual. I don't do it at the end of every class | Transcription |

| 9:08 - 9:23 | like you do. But I certainly do it at the end of every semester. But the whole idea is to-- how-- whole idea is to really come up with a way of making the students feel connected. And when you do | Transcription |

| 9:23 - 9:27 | that, in the classroom, you model what can be done in the community. | Transcription |

| 9:27 - 9:28 | Outside the classroom. | Transcription |

| 9:28 - 9:40 | If you do that in the community, you model what can be done in the world. And it seems to me your perspective has always been the extended community, you know. | Transcription |

| 9:40 - 9:49 | Yeah, I mean, even when we first came on the scene-- and you know, one of the things that you see is happening, when people really want to, in a sense, not open their eyes and listen, | Transcription |

| 9:50 - 10:03 | I'm always so, so surprised at people who have formed an opinion of you in 1965, and they still have the opinion in 2004. It shows two things. It's shows that the person has not grown, and the person | Transcription |

| 10:03 - 10:04 | thinks you have not grown. | Transcription |

| 10:04 - 10:21 | It's like the great Brecht, you know, used to do like these little small pieces similar to what Baraka does, you know? And he says in it, a friend came up and said "How are you doing? How are you | Transcription |

| 10:21 - 10:28 | doing? How are you feeling?" You know? And he says, "I'm doing fine, I'm doing fine." He says, "and you haven't changed a bit." | Transcription |

| 10:29 - 10:39 | And he looked at him in a very strange way and said "there's something wrong with that." Why? Because, if you haven't seen me in 20 years, my sis, you better believe I've changed. The wrinkle here is | Transcription |

| 10:39 - 10:48 | for a reason, you know, you know, the crease here for a reason. You know, the gray hair is for a reason. You know, I don't, I mean-- someone said, "Well, why don't you just dye that hair, Sonia. So | Transcription |

| 10:48 - 10:50 | then-- and don't tell your age, because then people won't know," | Transcription |

| 10:51 - 11:01 | I said, I want people to know that I have lived these years. I want people to know that this is what this is about. And this right here came from a demonstration, you know, when I turned, and I was | Transcription |

| 11:01 - 11:10 | knocked down, you know, and I got up-- couldn't get to ice, because I wasn't in my house, putting ice on it. So therefore every time, initially, when someone looked at it and said, "Oh God, Sonia, | Transcription |

| 11:10 - 11:16 | that's terrible there." And I looked at and I said, you know, uh huh. It could be terrible, but it could be for a reason, too. | Transcription |

| 11:16 - 11:27 | And I think everything is for a reason, you see, at some particular point. And I think that is what is important. I was just in Rome, for this great Interdependence day. And you had prime ministers | Transcription |

| 11:28 - 11:40 | and, and diplomats from all over the world. And I opened the conference with a poem that I did about Interdependence day, because the theme is that we're all interdependent as people, you know, in our | Transcription |

| 11:40 - 11:44 | own countries, in our separate countries, and then in the world, countries are interdependent. | Transcription |

| 11:44 - 11:54 | And when we truly understand that, then we move on a different level with each other. Because then you don't say to the person, I'm going to bomb-- you bomb me, then I bomb you next. When you're | Transcription |

| 11:54 - 12:01 | interdependent, then you go to people, then, who can say how do we reconnect because we've gotten disconnected at some point? | Transcription |

| 12:01 - 12:18 | Exactly. Because I was thinking that there must be some people in Iraq today, who are so convinced that they are being under-- they're under attack. I'm sure they have in their | Transcription |

| 12:18 - 12:27 | heads, this poem by Countee Cullen, "If we must die let it not be like hogs/ Hunted and pinned, in some inglorious spot." | Transcription |

| 12:28 - 12:42 | We have to really understand that they are just like us, they feel like us. And sometimes we let the media convince us that what is going on over there has no connection with us, at all. | Transcription |

| 12:42 - 12:46 | Right. Not Countee. Yeah. Yeah, I was just saying that's-- | Transcription |

| 12:46 - 12:46 | What? | Transcription |

| 12:46 - 12:49 | That's not Countee. Oh, I'm sorry. | Transcription |

| 12:49 - 12:49 | Did I say Countee? | Transcription |

| 12:49 - 12:49 | Yeah, right. | Transcription |

| 12:50 - 12:52 | Oh no, it's not Countee, that's right. I said Countee Cullen. | Transcription |

| 12:52 - 12:54 | Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Right. Yeah, that's all right. We'll correct it. | Transcription |

| 12:54 - 12:55 | Alright. It's Claude McKay | Transcription |

| 12:55 - 12:55 | Yeah, Claude McKay. | Transcription |

| 12:55 - 12:56 | Yeah, that's exactly right, yeah. | Transcription |

| 12:56 - 13:12 | Yeah, "If We Must Die." My sister, what we truly understand at some point, is that we have, all over the world, bunches of old men and women, you know, who know one way to deal with the | Transcription |

| 13:12 - 13:20 | world. And that is through fire, through killing, through bombings, through, you know, oppression, whatever. | Transcription |

| 13:20 - 13:29 | What we're saying at some point, what I tried to say to the young people yesterday, is that there's a new way of looking at the world. And one of the ways that we have moved with our poetry, you know, | Transcription |

| 13:29 - 13:39 | going from one point to another point-- when I first came on the scene, as other people came on the scene, we didn't know we had been enslaved. So we went into the library and said, Wow, God, we were | Transcription |

| 13:39 - 13:46 | enslaved, no one told us-- for insatance my momma didn't tell me I was enslaved-- when we found that out, what did we do? We were-- we attacked everybody, then-- | Transcription |

| 13:46 - 13:55 | Everybody, didn't matter who you are, were like, 'bu-bududu', and even our parents. So, America said, How could you attack me? I've been good to you. Why are you calling me those names? Like, whitey, | Transcription |

| 13:55 - 14:01 | whatever. And you know, because-- I said to someone finally, well Black [inaudible] folks have always called you names. | Transcription |

| 14:01 - 14:10 | Only because we had no power. So the best thing to do was like-- and I said that, but that's a Black thing. I mean, that's like when I grew up, you know, in Harlem, you played the dozens, you know, | Transcription |

| 14:10 - 14:23 | you signified on people. So I said to-- a long interview with someone that (which they never printed) in the New York Times, I said, this is about signifying, you know, so you cannot review a book of | Transcription |

| 14:23 - 14:30 | my poetry or anybody's poetry, unless you understand the culture of the people. You assume that you raised us all just like Topsy. | Transcription |

| 14:31 - 14:40 | We are saying, you did not raise us like Topsy, you know, we come with new information. So when I write this particular poem, you've got to come with information. For instance, when I used to teach | Transcription |

| 14:40 - 14:49 | Yeats, and I came across a poem, and I said now is he into mystical stuff here? You know, is he into whatever. | Transcription |

| 14:49 - 14:58 | So there was an authority on Yeats and I knocked on his door at Temple, and I sat down-- and I sat down with him, he said, 'Sonia, you're right. Very few people pick that up.' And I said, well only | Transcription |

| 14:58 - 15:07 | because I was a poet, another poet reading him. So I said, well, talk to me about it. He did, I took notes, you know. From then on that man spoke to me on that campus, but he hadn't done it before. | Transcription |

| 15:07 - 15:08 | Yeah. He respected you, yeah. | Transcription |

| 15:08 - 15:15 | So I said, if you're going to teach me, you just can't walk in and teach me or some of these other people, without understanding that there's a culture, but if you understand there's a | Transcription |

| 15:15 - 15:20 | culture, then you assume, then-- the assumption must be you're human. You know? | Transcription |

| 15:20 - 15:24 | What was the cultural moment for you, when you knew that you were going to be a writer? | Transcription |

| 15:25 - 15:38 | Oh gosh. You know, I think... I do think I might have known that at an early age. But it was, um... I always know, when I teach a workshop, the people who really truly have talent, and | Transcription |

| 15:38 - 15:44 | are really born poets, right? And the ones who just learned it, and can write a poem through, you know, craft, and that's about it. | Transcription |

| 15:45 - 15:56 | But I-- Well, I began to write poetry after my grandmother died when I was six, you know. And, but I didn't take it seriously, it was just something I did. But it saved my life, after my grandmother | Transcription |

| 15:56 - 15:58 | had died, after mama had died. | Transcription |

| 15:58 - 16:09 | But I think in a very serious way, I-- all through, during my university years, I would take these little writing classes, and it was like, I was always like, ignored, whatever etcetera. And so even | Transcription |

| 16:09 - 16:19 | when I got out of Hunter and was going to NYU, I'd do these workshops, and they would talk about everybody's poem-- now, I'm not writing anything radical, I'm just writing. But the point is that I | Transcription |

| 16:19 - 16:27 | look back on it now writing my memoir now, I was the only woman in there, and I was the only Black. So poetry was all for white males, | Transcription |

| 16:27 - 16:42 | you see, not even women. Adrienne Rich says, (in one of the anthologies she says), I really got up on stage one day and announced, I am a woman poet, okay, after I read the black poets in America, who | Transcription |

| 16:42 - 16:51 | were saying, I am a black poet. And that's why I'm talking about the kind of influence that we had on people, because we identify ourselves, you know, from jump street, you see. | Transcription |

| 16:51 - 17:03 | I really discovered it when I studied with a woman by the name of Louise Bogan. You go into American literature, and there she is, fine poet and editor for The New Yorker. You know, I mean, the poetry | Transcription |

| 17:03 - 17:12 | editor for The New Yorker. I walked into a class of 45 people at NYU, my sister. I sat by the door, because no one had ever wanted to even discuss what I was writing, | Transcription |

| 17:12 - 17:23 | and the first night she says, Does anyone have a poem? That's like asking a bunch of alcoholics, if they got a bottle someplace. We all went in our pockets, like this, you know, I went in my pocket, | Transcription |

| 17:23 - 17:34 | and I raised my hand and said find out now, but I raised my hand. She said, Come up front, tell me your name. I did. I read the poem and she... the whole class went [raises hand], responds to it. | Transcription |

| 17:34 - 17:49 | First time I had response, you know, and she said, "And if you had really read that poem out loud, Sonia, you would have heard the following." And like, Lo, I stayed. I studied. And then I finally | Transcription |

| 17:49 - 17:59 | asked her one day in her office, I said, I want to know, do I have talent? She said, "What do you want to know that for Sonia?" I said, well, I said I'd like to know, because, you know, I wanna know | Transcription |

| 17:59 - 18:03 | if I'm wasting-- I didn't say that, because I really didn't think I was wasting my time, right? | Transcription |

| 18:03 - 18:14 | Because it was in that workshop that I published my first poem. Out of all that class, and I brought in bottles of wine to NYU, you know, at night, you know, and passed it around with little cups. And | Transcription |

| 18:14 - 18:28 | because she taught us from the jump street, the first day, she said, get a notebook. Put down on one side the Nation, Address, day sent, three poems, no more than three poems, New Yorker, the Mass | Transcription |

| 18:28 - 18:31 | Review, New England Review, page, page, and start sending your poetry out. | Transcription |

| 18:31 - 18:42 | I did it, you know. First time I sent it, however, I took it to the mailbox across from where I lived, right? And by the time I got back home, the reply was there. No, thank you, right. But I-- | Transcription |

| 18:42 - 18:43 | But it's so empowering to do that. | Transcription |

| 18:43 - 18:45 | It is-- I make my students do it in workshop. | Transcription |

| 18:45 - 18:45 | Yeah. Yeah. I do that as well, yeah. | Transcription |

| 18:45 - 18:52 | Oh, yeah. You know, and when I'm editing something, or someone else is editing something I say, write them with this poem, it's good, tell them you're in my workshop. And you know, | Transcription |

| 18:52 - 19:03 | you've seen my students get published, along with major poets, you see. That is what you do. You push this thing called poetry, because poetry is one of the most important things that will keep us | Transcription |

| 19:03 - 19:04 | human on this earth. | Transcription |

| 19:04 - 19:14 | Yeah, we did a children's workshop yesterday. And the poems that came out of that workshop. Amazing for 12 to 14 year olds. | Transcription |

| 19:14 - 19:15 | Oh, no, not at all. | Transcription |

| 19:15 - 19:16 | And that young -- | Transcription |

| 19:16 - 19:18 | Yeah. The one that read last night, yes. | Transcription |

| 19:18 - 19:19 | The one she read was just wonderful. | Transcription |

| 19:19 - 19:20 | Wonderful. | Transcription |

| 19:20 - 19:33 | She talked about all of the different positive aspects of being Black, you know, and darkness, that was really wonderful. You know, I was thinking, you read a poem yesterday, and you | Transcription |

| 19:33 - 19:36 | called it a "Poem for Some Women." | Transcription |

| 19:36 - 19:36 | Yeah. | Transcription |

| 19:37 - 19:50 | And, what was the impetus for that poem? It's a very painful poem. A colleague of mine, walked out of the auditorium and was visibly moved, and told my husband, he just thought that | Transcription |

| 19:50 - 19:53 | was one of the most powerful poems he'd ever heard read. | Transcription |

| 19:54 - 20:04 | My sister I was watching television one night, you know, at the end of the day. I was getting my tea to go upstairs to, you know, sit-- plop, prop myself up a bit and write or read | Transcription |

| 20:04 - 20:16 | before I went-- go to sleep. And the news cast came on and this woman said today, today, today, it was reported that a woman in North Philadelphia (which identified her as Black, or Puerto Rican, | Transcription |

| 20:16 - 20:24 | right, Latina, you know), took her child into the crack house and left her. And then there was this silence, which meant like, Oh, those people do terrible things to their children. | Transcription |

| 20:26 - 20:37 | And I went upstairs trying to forget it. And I even, you know, read a bit, you know, brushed my teeth, you know, washed my face, pull the covers up, and got up in the middle of the night, and started | Transcription |

| 20:37 - 20:42 | writing that poem. And that poem is for some women, not all women. | Transcription |

| 20:42 - 20:52 | That poem is about the question that I wrote in the margin, always-- I always ask my students when they're writing, what is the first question that comes to your head that motivates you to write this | Transcription |

| 20:52 - 21:04 | poem? The question was, how have we gone from women on the slave auction blocks, you know, saying master master, please don't take my child away from me. How have we gone from there to taking that | Transcription |

| 21:04 - 21:06 | child in the crack house and leaving her for a week? | Transcription |

| 21:07 - 21:07 | Yes. | Transcription |

| 21:07 - 21:20 | You know, and it was in that space, that I began to write that poem. You know, in that woman's voice, you know, who is still human. You understand? When you just do the cold facts, | Transcription |

| 21:20 - 21:32 | she's not human. She has no breath. She has no blood. She has nothing except, that's what she did, you see. But the woman is human, you know. I mean, this woman who lives in her neighborhood, you | Transcription |

| 21:32 - 21:37 | know, and can get crack, you know. She can find the crack house, but the police can't find the crack house. | Transcription |

| 21:37 - 21:44 | But the children can tell you where the crack house is, you know. Everybody on the block can tell you where the crack house is, and it never gets busted, you know what I'm saying? So here she is, | Transcription |

| 21:44 - 21:52 | marching in, and she sees this man who says, "I don't want you." She says, "I'm gonna give you my body." And he says, "I don't want you, but I want a virgin." | Transcription |

| 21:52 - 22:07 | What kind of person? What kind of male, you know, looks at 11 a 10, a nine an eight, a 12 a 13-- I'd go up to 16, even, you know-- year old, and you see, you know, you don't see a human being you | Transcription |

| 22:07 - 22:15 | know, you don't see a little girl, right? You know, but you see a virgin, how can you call a 12 year old a virgin? That's a little girl, maybe one day removed from dolls. | Transcription |

| 22:15 - 22:26 | So I wanted to have all of that in that piece, you see. And this woman, and she comes back singing "Mama's little baby loves shortening, shortening, Mama's a little baby loves shortening bread, put on | Transcription |

| 22:26 - 22:28 | the jacket, put on the jacket." | Transcription |

| 22:28 - 22:37 | Because you see, one of the times when I'm pushed up against the wall with some people, and I have moved to a point where I don't curse people out, you know, where I don't attack-- you know, go and | Transcription |

| 22:37 - 22:46 | say get out of my face, you know, you're in deep trouble, [inaudible] or whatever. But I'd say you know, can you tell me my brother, what I did to offend you? You know, right. And then sometimes | Transcription |

| 22:46 - 22:54 | people say 'well lalalala', I said, well, I'll come back to you. You know, we'll talk later, and I walk away. But I might walk away humming. | Transcription |

| 22:54 - 23:04 | Because the humming gets me through that next moment, you know. That humming, makes me understand at some point, there are some people, you know, who really have been taught never to go below this | Transcription |

| 23:04 - 23:16 | area. They've never been taught to go to the heart, or even the bloodstream, or even the mind, or above the mind at all. That their thing is always let us be combative. Let us-- oh, let me stay right | Transcription |

| 23:16 - 23:20 | here in the gut, and in the other part, in the genitals, you know what I'm saying? | Transcription |

| 23:20 - 23:30 | Then, but the country keeps you on that level. If it can keep you hungry always, and stuffing your mouth with food, you know. If it can keep you always looking at fighting, people fighting all the | Transcription |

| 23:30 - 23:39 | time so you get a hard on, you know, like, "Woooo, did they get that--", whatever, you know, if they can keep the young girls itching all the time to jump in somebody's bed, because she thinks that's | Transcription |

| 23:40 - 23:43 | gonna make her a woman, then you control the populace. | Transcription |

| 23:43 - 23:54 | But if you move their eyes up to the heart, and if you have a heart, you know, you do not kill. You know what I'm saying? You know, and if you have a mind, you'll look at it in a different way and | Transcription |

| 23:54 - 24:05 | begin to say, Aha, but if you have the spirit, you know, spirit mixed with the mind, also, do you know what I'm saying? The spirit and the soul with the mind, then something else happens. | Transcription |

| 24:05 - 24:14 | And it has been that kind of motion and movement that I've tried to do with my poetry. And in that piece, that's a hard, piece because all of a sudden, I don't think you remember that poem when I read | Transcription |

| 24:14 - 24:23 | to you years ago, and I said, and then Joanne I said, I have moved to another level, I don't write this kind of poem anymore. And then I heard myself say it later on. I said, oops, what are you | Transcription |

| 24:23 - 24:33 | saying? If it's happening, you can't move-- you can't move to another level. What do you mean you've moved to another level? Girl catch yourself, you know, watch yo mouth as the old folks used to say, | Transcription |

| 24:33 - 24:35 | you know, girl, watch yo mouth, what are you saying? | Transcription |

| 24:35 - 24:36 | Other directions maybe. Are there-- | Transcription |

| 24:37 - 24:38 | Of course there are other directions! | Transcription |

| 24:38 - 24:38 | Yeah. Yeah. | Transcription |

| 24:38 - 24:47 | But the point is what I understand is that I can do this piece-- a very middle class woman said to me, 'Ah, Professor Sanchez, I just love your poetry. It is so lyrical. But why would | Transcription |

| 24:47 - 24:60 | you why something like this?' You know? And that's like, just recently-- you know, in the airport, when, you know, they grab you because you you're talking about the country and the war, and Bush and | Transcription |

| 24:60 - 25:03 | all this stuff, you know, that's happening. And [Inaudible], you know, they-- | Transcription |

| 25:03 - 25:05 | Then you've become a security risk. | Transcription |

| 25:05 - 25:14 | Yeah. And they said, they said-- and they tag you, you know? Well, Grace Paley, the writer, all of us. I mean, the ACLU called me and said, you know, it's a list with all you peace | Transcription |

| 25:14 - 25:24 | people on it, you know what I'm saying? So we want you to know, so I put my name on the thing, where they were going to file to get that list, so it could be published as such. But they grabbed me-- | Transcription |

| 25:25 - 25:27 | but I'm coming out of Syracuse, my sister. | Transcription |

| 25:28 - 25:40 | And the woman never looks up, the guy didn't even-- nothing went 'ding ding ding ding ding ding'. Nothing with ding, ding, ding, ding at all. But he saw the color code that they have on there. He | Transcription |

| 25:40 - 25:51 | said, we need you on the side. So I said, Oh, is there a problem? I didn't hear anything go dingaling, dingaling. You know? And he said simply-- well, yeah, that's what I was told. I mean, I was told | Transcription |

| 25:51 - 25:55 | by the brothers outside, but I wanted him to say it too, because his [inaudible] they won't say it. | Transcription |

| 25:55 - 26:05 | They just say oh, this is just something that we do with a few, you know, chosen people. But he said it because he saw me looking at him. So the black woman came along, she never looked up at all. She | Transcription |

| 26:05 - 26:21 | just said, come this way, grabbed my briefcase, and my purse, and she says, "stand back, Stand back." And so, she opened my purse, and she took my stuff and threw it like it was dirt. And dirty. | Transcription |

| 26:21 - 26:32 | And I stood there just looked at her. I kept looking at this sister thinking, you know, mmm, mm, it's hard, you know, you know, it's hard being human. Then she put my stuff in-- threw it back in, no | Transcription |

| 26:32 - 26:43 | order. Zipped it. Then she opened my briefcase and the first thing she saw was my picture on a book, and she said "Miss Sanchez." She looked, she said "Oh"-- looked at me for the first time. | Transcription |

| 26:43 - 26:55 | And I thought how often we go through life, jobs, all over and we never look people in the eye. Because we're afraid of what we will see. We will see ourselves when we look people in the face, and we | Transcription |

| 26:55 - 26:57 | don't want to see ourselves sometimes. | Transcription |

| 26:57 - 27:05 | She said "why"-- she whispered, "why are they doing this to you?" I said my sister-- and I whispered back "they're doing"-- I leaned over, "they're doing it because I'm talking about the war, against | Transcription |

| 27:05 - 27:19 | the war, about peace, whatever et cetera," she said, why don't you stop? I said, my dear sister, if I stop, if I stop, if I and others stop, who's gonna do it? And she lowered her head, and she never | Transcription |

| 27:19 - 27:23 | finished going all the way through. She just kind of looked through it. And then she opened my bag. | Transcription |

| 27:24 - 27:25 | You know, the typical reaction-- yeah. | Transcription |

| 27:25 - 27:41 | --And took the stuff out the bag. And started to put it back in. The right way. And she turned towards me, and she handed me my things, and she said 'I'm sorry. I'm so sorry.' And I | Transcription |

| 27:41 - 27:49 | said, sister, I'm not here for your job. I know you're sorry. But that's the state of the country now. And I walked on, you know? | Transcription |

| 27:50 - 27:56 | Yeah, we've gotten to the point where it's very hard to see other people's pain. It's very hard, | Transcription |

| 27:56 - 27:56 | Well, | Transcription |

| 27:56 - 27:60 | And it's very hard to confront the evil. That is-- | Transcription |

| 27:60 - 28:11 | It's very hard to see your own pain, you see, if you see my pain then you know you also have pain. And most of us you know, camouflage it, disguise it. Drugs, alcohol, lots of men, lots | Transcription |

| 28:11 - 28:20 | of women, you know, shopping on your lunch hour paying $2,000 for some clothes, you know, that's another way of doing it. You know what I'm saying? Whatever. | Transcription |

| 28:20 - 28:31 | You know, going home, turning on the idiot box watching stupid stuff on television that you laugh at-- laughing at yourselves, then going upstairs, screwing, getting up the next morning going to work. | Transcription |

| 28:31 - 28:38 | Oh, I'm happy. I'm happy, I'm happy. And this is how a country controls people in such a way where they will not speak out. | Transcription |

| 28:38 - 28:51 | And what we're trying to do with this poetry-- when I read that poetry, I read that poem to a group of young women who were just returning back to school, and there were about 20 Puerto Rican women, | Transcription |

| 28:52 - 29:02 | and 20 Black women. And I read that poem out loud. It wasn't, it wasn't in the book at that time, right. It hadn't been published, It was almost published. | Transcription |

| 29:02 - 29:14 | And, after I'd done the book that they had gotten with all the questions, whatever. I said, the last poem I'll read, I took a manuscript and I read that poem, and there was this silence. And then a | Transcription |

| 29:14 - 29:26 | voice from across the room said, 'Hey, hey, that's just like Maria, ain't it?' I wanted to collapse. I wanted to cry. I wanted to get down on my knees. I wanted to say no, no, no, no, no, no, no. But | Transcription |

| 29:26 - 29:32 | I knew it wasn't true. And then a voice says, tell us Professor Sanchez, why is that wrong? | Transcription |

| 29:33 - 29:45 | And God, I understood the disconnections from teaching. That they should have been taught that by a mother, by an aunt, by a grandmother. I mean, it was-- I mean, they understood it was wrong, but | Transcription |

| 29:45 - 29:56 | they meant more than that. They meant like, "tell us the cultural information that would keep us from doing that. Tell us what we hold on to so that we would never then take our children to a crack | Transcription |

| 29:56 - 29:57 | house" is what they wanted. | Transcription |

| 29:57 - 30:07 | What they needed. You know what I'm saying? That's what they wanted. That's what they needed. And so I-- ready to go out of there because I'm going for PEN, the writers organization, I spent my hour | Transcription |

| 30:07 - 30:09 | in there. I, you know, getting ready to order-- | Transcription |

| 30:25 - 30:37 | --From that experience, so I mean I had to go back and repeat it, again. I had to teach them the culture in such a way-- being women, being human-- that they would take that with them so it went | Transcription |

| 30:37 - 30:40 | beyond the poem. Do you know what I'm saying? | Transcription |

| 30:40 - 30:53 | And I got in, and I said to the brother, I looked up the guy's name. I said, you know, Mr. Santiago, I said, I'm going to 10 West 135th Street, my father's house. I said, I don't want to go downtown. | Transcription |

| 30:53 - 31:03 | You know, I know the Bronx, and I'm from New York. I said, but I have to close my eyes to go to sleep, I said. And I'm tired. I'm really exhausted, but please get me there. | Transcription |

| 31:03 - 31:13 | And he said, "Don't I know you? Aint I seen you on television?" I said play it, Sonia. I said yes you have my brother. He said, "Oh, yeah, yeah, I'll get you there. I'll get you there sister." And I | Transcription |

| 31:13 - 31:27 | was out. I mean, I was out. Because I had to, I mean, to keep from crying, to keep from collapsing, and to say it over and over again, 'till it was ingrained, not only here, but here. And here. And | Transcription |

| 31:27 - 31:32 | here. And here. And here. You know, then I felt comfortable leaving. | Transcription |

| 31:32 - 31:42 | And then I heard this voice say, "Ms. Sanchez, wake up, wake up." And I was in front of my father's you know, and I said, "can I--", And he said, "don't pay me nothing. No, no, no, don't pay me | Transcription |

| 31:42 - 31:52 | nothing. Don't pay me nothing. It's my privilege," whatever. And I got out and went up to my father's house who was really not well, and you know, I really didn't-- you know, it's one of those days so | Transcription |

| 31:52 - 31:59 | I said, Listen, Dad, do you know what just happened to me? Then I had to go into another arena, you know, with him. | Transcription |

| 31:59 - 32:17 | But my sister, that's how I see this thing called poetry. Most of the poets I know, from Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde, June Jordan, Gwendolyn Brooks, Margret Walker. I said Alice Walker, Amiri Baraka, | Transcription |

| 32:17 - 32:32 | Haki Madhubuti, Askia Touré. Neruda, Pablo Neruda. Nicolás Guillén, you know, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, Achebe, all these people. You know, we're on that-- in that same, | Transcription |

| 32:32 - 32:44 | same-- Ginsburg. We're in that same-- and Paul Blackburn, a man I teach from, from the Beat Movement. You should teach Paul Blackburn. One of the first men who came up to me and said-- poet said to | Transcription |

| 32:44 - 32:54 | me, Sonia, you're not only a poet, but you're very human. He said "now you're New-- a New Yorker, though." He said, "You always socking us out telling us where we're wrong, you know, and cursing us | Transcription |

| 32:54 - 32:56 | out," but he said, "I know that," you know. | Transcription |

| 32:56 - 33:05 | If you know the culture, you know that-- to New York Times the-- "Oh, how could you write this about us?" You know, whatever, "we loved you." And I said, no you don't mother, you don't, you know, | Transcription |

| 33:05 - 33:14 | because if you loved us you wouldn't have enslaved us. So don't go there. But if you come at me right, we can have a discussion about it. You understand what I'm saying? The difference? And Paul | Transcription |

| 33:14 - 33:25 | Blackburn is a really great poet. Paul Blackburn's a really great poet, because he really was a fine writer, you know, a fine-- so if you ever check him out from that period it's worth [inaudible] | Transcription |

| 33:25 - 33:26 | teaching. | Transcription |

| 33:26 - 33:27 | The Beat movement. | Transcription |

| 33:27 - 33:30 | Uh yeah, the Beat movement and really worth teaching a great deal. | Transcription |

| 33:30 - 33:43 | Allen Ginsburg I've taught. Allen Ginsberg and his experiment with communal life that, you know, only worked so well because of difficulties with human beings. But he wanted to | Transcription |

| 33:43 - 33:54 | isolate people and give them an opportunity to be in the wilderness and write, and then come back to the urban setting and see if their values have changed at all. But, | Transcription |

| 33:55 - 33:57 | Hey Joanne, we've got about five minutes left. | Transcription |

| 33:57 - 34:10 | Okay. Alright. Well, let's go to the very last question that I think you you've spoken to. "We are each other's harvest;/ We are each other's business;/ We are each other's magnitude | Transcription |

| 34:10 - 34:11 | and bond." | Transcription |

| 34:11 - 34:28 | I love that line from Gwendolyn Brooks' poem on Paul Robeson, and I mentioned Paul Robeson yesterday, when I introduced Amiri Baraka. Because it occurred to me that we don't really know how to treat | Transcription |

| 34:29 - 34:31 | genius men who are Black. | Transcription |

| 34:31 - 34:32 | Genius anybody. | Transcription |

| 34:32 - 34:34 | Or genius women, who are Black. | Transcription |

| 34:34 - 34:39 | They never put women in a genius class, but we are. That's why, you know me I'm a corrector. You know, you know me. | Transcription |

| 34:39 - 34:40 | Yes, exactly. Exactly. Yes, yes indeed. | Transcription |

| 34:40 - 34:54 | And, you know, and I was saying, you know, when we don't know what to do with them, we call them dangerous. And we attack them, we harass them, we put them on all kinds of security lists. Women and | Transcription |

| 34:54 - 34:59 | men. And then, if they die conveniently, we put their heads on a stamp. | Transcription |

| 34:59 - 34:60 | Oh yeah. | Transcription |

| 34:60 - 34:60 | I thought about-- | Transcription |

| 34:60 - 35:01 | It's okay then. | Transcription |

| 35:01 - 35:19 | Yeah, it's okay then. And what your poetry's always been for me, is a poetry that allowed me to really feel what other people felt. I will never forget the first time I heard, "Don't | Transcription |

| 35:19 - 35:21 | Never Give up on Love." | Transcription |

| 35:21 - 35:21 | Hah, thank you. Yeah, yeah. | Transcription |

| 35:22 - 35:38 | And I sat in the auditorium at Leader University, and I wept. Because I realized that you were saying to all of us, whatever the situation, whether it's a love relationship with a | Transcription |

| 35:38 - 35:48 | man, or a relationship with his daughter or mother, that love is the final thing that you don't discard. | Transcription |

| 35:49 - 36:04 | You may want to forget about the experience, you may want to even sort of put the person on hold for a little bit, but you never give up on love. And I've seen you show that grace of the universe | Transcription |

| 36:04 - 36:12 | through all of your poetry. You talk about children in El Salvador, and Guatemala, when you talk about children in Rwanda, and you talk about-- | Transcription |

| 36:12 - 36:13 | And Sudan. | Transcription |

| 36:13 - 36:28 | And Sudan and Bosnia. You talk about the children in Iraq, when you talk about women in the-- in New York, in Chicago, in crack houses. When you talk about people who are oppressed, | Transcription |

| 36:29 - 36:34 | and people who often don't see anything that remotely resembles peace. | Transcription |

| 36:34 - 36:35 | Yeah. | Transcription |

| 36:35 - 36:46 | You are embracing the universe. And that is what I see as just this remarkable thing about you that always keeps me coming back to your poetry, and of course, coming back to you, as | Transcription |

| 36:46 - 37:02 | a friend. Because I know that when I hear from you, it's going to be the truth, it's going to be kind, it's going to be also very, very precise. In terms of what you know about human nature, and what | Transcription |

| 37:02 - 37:03 | you know about our culture. | Transcription |

| 37:03 - 37:15 | I remember seeing this little Sudanese boy. They asked him, What do you want? And the person who asked him was an American, and he says, I want a bed, and some food to eat. And I said, | Transcription |

| 37:15 - 37:19 | how have we taken children to just the bare essentials. | Transcription |

| 37:20 - 37:32 | And the point of all of this has been-- from the Black Arts Movement to today-- has simply been you know, it was never about, you know, all of us being in poverty, but also saying to everybody, we can | Transcription |

| 37:32 - 37:41 | all move to a different way of looking at the world and living, you know, it's to bring people out of this poverty of the mind, spirit, you know, heart and soul. | Transcription |

| 37:42 - 37:54 | And I remember looking at that little boy's face, and I thought to myself, how can we as human beings in this country, you know, do this? How can people in Sudan, do this, where you have children who | Transcription |

| 37:54 - 37:60 | are asking only for a bed to sleep, or some food to eat? Not a computer, not a -- whatever, you know. | Transcription |

| 38:01 - 38:12 | But not a television, you know, not books, whatever. But just that, he's saying, you have brought me down to the bare essentials. And I cried out, as this child-- "just give me a bed and some food to | Transcription |

| 38:12 - 38:16 | eat." And we've tried to do more than give you a bed and some food to eat. | Transcription |

| 38:17 - 38:18 | Thank you so much. | Transcription |

| 38:18 - 38:21 | Thank you you my sister. Thank you very much. | Transcription |

| 38:22 - 38:22 | Oh, boy. | Transcription |

| 38:25 - 38:26 | [Inaudible] if you guys just talk to each other. | Transcription |

| 38:27 - 38:38 | Okay, I was I was reaching back here. I was trying to find my tissue, the tears were running down my face, and I couldn't, I couldn't reach anything. But you know, I don't know | Transcription |

| 38:38 - 38:40 | whether we covered the questions that you wanted. | Transcription |

| 38:41 - 38:45 | We did! I tried to. I read the questions. So what I did is that I weaved-- | Transcription |

| 38:45 - 38:45 | Yes you did. | Transcription |

| 38:45 - 38:52 | --some of the answers to-- although the question was not asked. I weaved it, I tried to go, yeah. | Transcription |

| 38:53 - 38:53 | Oh my gosh. | Transcription |

| 38:54 - 39:00 | Okay. Yeah. Because I remember seeing the questions and then that's why I weaved and went places, Okay. Yeah. | Transcription |

| 39:01 - 39:08 | It was, it was wonderful. You took me back I, you know I did forget that you were in here for a few minutes. Oh, my God. Well. Whoo!" | Transcription |

| 39:08 - 39:10 | Thank you. Thank you. Thank-- | Transcription |

| 0:01 - 0:08 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 0:12 - 0:27 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 0:45 - 0:55 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 4:35 - 4:48 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 5:25 - 5:36 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 8:24 - 8:33 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 8:33 - 8:37 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 8:37 - 8:38 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 8:38 - 8:38 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 8:38 - 8:38 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 8:38 - 8:40 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 8:40 - 8:51 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 8:51 - 8:52 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 8:52 - 9:08 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 9:27 - 9:28 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 9:28 - 9:40 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 9:40 - 9:49 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 12:01 - 12:18 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 12:42 - 12:46 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 12:46 - 12:46 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 12:46 - 12:49 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 12:49 - 12:49 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 12:49 - 12:49 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 12:50 - 12:52 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 12:52 - 12:54 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 12:54 - 12:55 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 12:55 - 12:55 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 12:55 - 12:56 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 12:56 - 13:12 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 15:07 - 15:08 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 15:08 - 15:15 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 15:20 - 15:24 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 15:24 - 15:38 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 18:42 - 18:43 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 18:43 - 18:45 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 18:45 - 18:45 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 18:45 - 18:52 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 19:04 - 19:14 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 19:14 - 19:15 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 19:15 - 19:16 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 19:16 - 19:18 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 19:18 - 19:19 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 19:19 - 19:20 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 19:20 - 19:33 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 19:36 - 19:36 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 19:37 - 19:50 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 19:54 - 20:04 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 21:07 - 21:07 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 21:07 - 21:20 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 24:35 - 24:36 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 24:37 - 24:38 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 24:38 - 24:38 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 24:38 - 24:47 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 25:03 - 25:05 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 25:05 - 25:14 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 27:24 - 27:25 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 27:25 - 27:41 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 27:50 - 27:56 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 27:56 - 27:56 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 27:56 - 27:60 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 27:60 - 28:11 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 33:26 - 33:27 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 33:27 - 33:30 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 33:30 - 33:43 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 33:55 - 33:57 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 33:57 - 34:10 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 34:31 - 34:32 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 34:32 - 34:34 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 34:34 - 34:39 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 34:39 - 34:40 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 34:59 - 34:60 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 34:60 - 34:60 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 34:60 - 35:01 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 35:01 - 35:19 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 35:21 - 35:21 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 35:21 - 35:38 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 36:12 - 36:13 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 36:13 - 36:28 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 36:34 - 36:35 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 36:35 - 36:46 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 37:03 - 37:15 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 38:17 - 38:18 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 38:18 - 38:21 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 38:22 - 38:22 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 38:27 - 38:38 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 38:41 - 38:45 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 38:45 - 38:45 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 38:45 - 38:52 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 38:53 - 38:53 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 38:54 - 39:00 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |

| 39:00 - 39:08 | Joanne V. Gabbin | Speaker |

| 39:08 - 39:10 | Sonia Sanchez | Speaker |