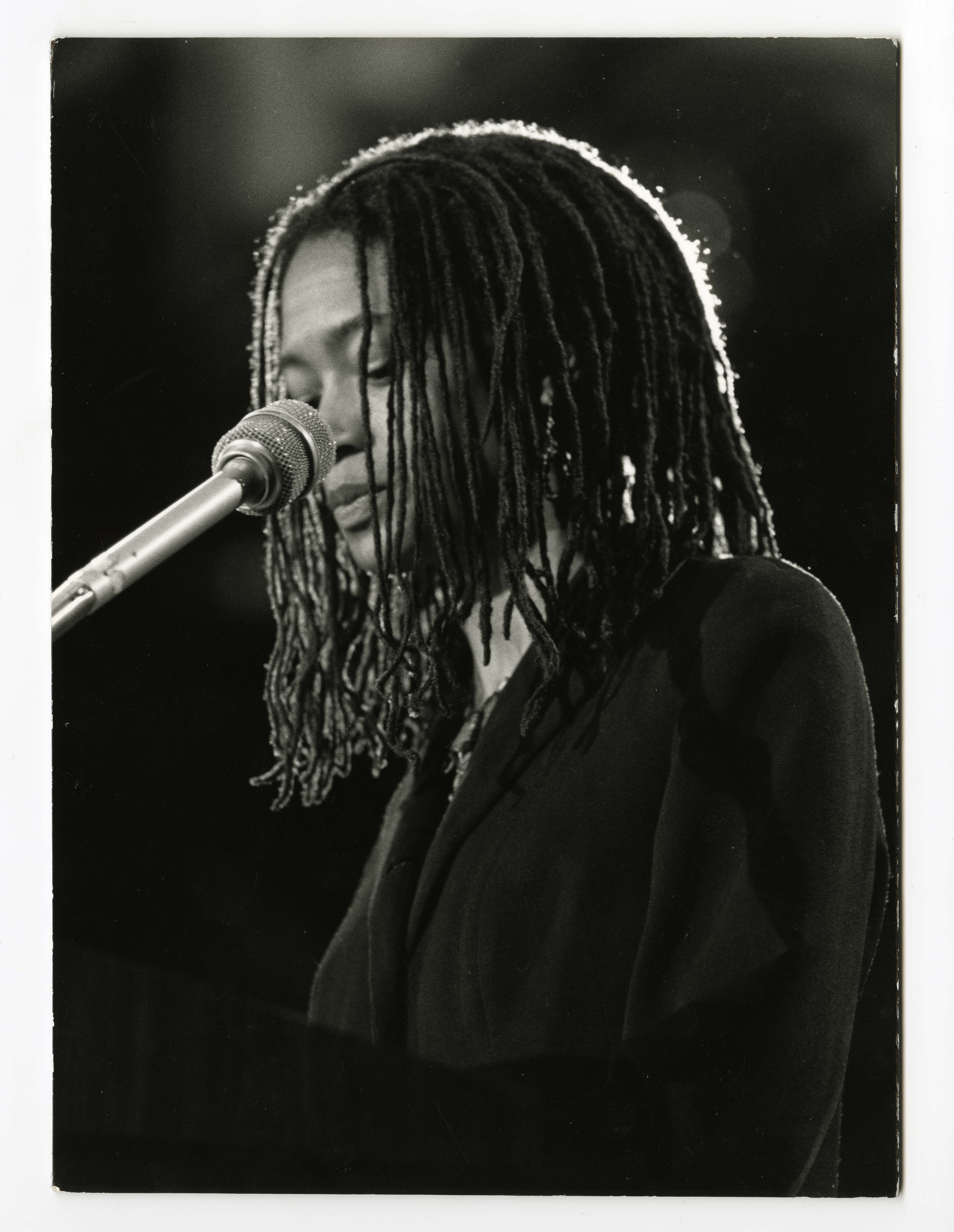

Sharan Strange

Sharan Strange is a poet, essayist, teacher, and theorist. In interviews she has emphasized how the political climate affects her experience of everyday life. Especially in these times, she feels a sense of responsibility to communicate truth, in opposition to the propaganda of false national and historical narratives. In her essay A Poetics of Empathy, she says: ”in the context of African American poetry from past to future, a poetics of empathy corresponds to a poetics of resistance that confronts apathy and assault with the prerogative, practice, and pressure of humanity.”[1] Her poetry reflects this philosophy.

Often Strange's poetry includes rich and haunting language capturing aspects of her childhood in the South. Contemplating various subjects including racist teachers, classmates, and girlhood, Strange weaves together beautiful lines out of complex, sorrowful encounters. In other poems, she constructs a deep sense of place, explores the significance of dreams, and speaks of combating suffering and oppression, past and present, through artistic resistance.

She has many influences, but has especially benefited from the work of Yusef Komunyakaa and Toni Morrison, with their sensitivity to the musicality of language and their visual genius. She also credits musicians, visual artists, choreographers, and filmmakers as influencing her work.

In her career she has engaged in the artistic community through The Darkroom Collective, an organization which she co-founded, and her contributions to journals such as Callaloo and American Poetry Review. Her writing has been presented in such places as the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, the Whitney Museum, and the Skylight Gallery in New York.

In this interview, Reggie Young and Sharan Strange discuss the importance of place, the function of emotional reserve in her poetry, and her historical counternarratives.

Reggie Young is a critic and a poet. He received his Ph.D. in creative writing at the University of Illinois. He has worked as a scholar and professor at Villanova University, LSU, Wheaton College, and the University of Louisiana. He has published critical works and poetry in African American Review, Oxford American, and Chicago Review, to name a few.

More Information:

Interviews and Essays:Interview[2] with Toi Derricotte. Strange and Derricotte discuss childhood, history, and spirituality in Strange's work.

Auburn Avenue interview, discussing The Darkroom Collective and Strange's take on the literary landscape of 2017.

"The Darkroom Collective and Post-Soul Poetics"[3], an essay written by Brian Reed. Provides a general history and restrospective of the collective, including focused discussion of the work of Strange, Thomas Sayers Ellis, Kevin Young, and others.

"Threads"[4], an essay by Sharan Strange. Addresses the malignant persistence of the confederate flag, white supremacy, and white privilege, as well as Strange's complicted relationship with the South.

Furious Flower Archive: Includes a brief bio, annotated text, and videos of Strange reading her poems "Offering" and "Barbershop Ritual".

Beltway Poetry Quarterly: Includes several of Strange's poems.

The Art Section: Displays two of Strange's ekphrastic poems alongside the Romare Bearden paintings that inspired them. Also includes audio and video of Strange reading the poems.

[1]: Strange, Sharan. "A Poetics of Empathy" in Furious Flower : Seeding the Future of African American Poetry. Edited by Joanne V. Gabbin and Lauren K. Alleyne. Evanston, Illinois: Triquarterly Books, Northwestern University Press, 2020.

[2]: Derricotte, Toi, and Sharan Strange. “An Interview with Sharan Strange.” Callaloo 19, no. 2 (1996): 291–98.

[3]: Reed, Brian. “The Dark Room Collective and Post-Soul Poetics.” African American Review 41, no. 4 (2007): 727–47.

[4]: Strange, Sharan. “Threads.” Callaloo 24, no. 1 (2001): 176–80.

Preferred Citation:

Sharan Strange Interview, 09/25/2004 (FF0137). Transcribed and edited by Evan Sizemore, 2021-2022, part of the Mellon-funded AudiAnnotate Audiovisual Extensible Workflow Project. Based on video recordings made by WVPT to document the second Furious Flower Poetry Center decennial meeting, September 23-25, 2004. Part of the Furious Flower Poetry Center Conference Records, 1970-2015, UA 0018, Special Collections, Carrier Library, James Madison University Libraries, Harrisonburg, Virginia, media file FF137. Collection finding aid: https://aspace.lib.jmu.edu/repositories/4/resources/487.Browser Directions:

Audio and video playback is activated by the timestamped annotation section you click in. Search field will find any word or phrase in the Transcription, Speaker or Environment annotation layers. Annotation layers can be ordered by Time (default), Annotation contents or Annotation layer labels by selecting the up/down arrows on the right. Speaker and Transcription layers are matching color-coded to facilitate reading.| Time | Annotation | Layer |

|---|---|---|

| 2:34 - 2:36 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 10:35 - 10:38 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 17:50 - 17:52 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 23:19 - 23:21 | [Cough] | Environment |

| 26:49 - 26:53 | [Cough] | Environment |

| 26:54 - 26:56 | [Throat Clearing] | Environment |

| 27:01 - 27:02 | [Soft Laugh] | Environment |

| 27:08 - 27:11 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 27:15 - 27:18 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 0:08 - 0:11 | S-h-a-r-a-n, S-t-r-a-n-g-e. | Transcription |

| 0:17 - 0:29 | Let me ask you-- you have a great name for a poet first of all, but what was your calling in the literature? Was there a work that you read some time or another that made you know you | Transcription |

| 0:29 - 0:32 | wanted to have an ongoing relationship with literature? | Transcription |

| 0:34 - 0:49 | I don't recall exactly a particular work. But I do remember at a very early age, just being fascinated with the way people spoke. Just fascinated with language. I grew up in the South. | Transcription |

| 0:49 - 1:02 | I grew up in what's possibly a typical Southern family in the latter half of the 20th century, where we had extended family, if not right in the household, in the community. | Transcription |

| 1:02 - 1:14 | I grew up around a number of people who were aunties and mothers and uncles and elders, and I was always fascinated by their conversations. The way they discussed their personal business as well as | Transcription |

| 1:14 - 1:16 | the business of the world. | Transcription |

| 1:16 - 1:30 | And so I think that first fascination with language and with the cadences of language, struck me and sort of got stored for a bit inside. And then when I went to school, and started reading things, | Transcription |

| 1:30 - 1:44 | got exposed to literature through my classes, that's when I think I decided that this was something that was-- something for me, if not a calling that I would find myself involved in at some point, | Transcription |

| 1:44 - 1:49 | but certainly something that I would stay fascinated with and connected with, for as-- you know, all my life. | Transcription |

| 1:50 - 2:01 | What about in terms of writing? When did you hear that call that told you that I'm a writer, especially a poet? When did you discover that you are a poet? | Transcription |

| 2:03 - 2:13 | That's hard to say, as well, but through The Darkroom Collective, which was a collective of writers of color that I became involved with in Cambridge. After college, after my | Transcription |

| 2:13 - 2:26 | college years, I would say that I decided that this is serious business, and I'm going to honor this voice that I had been capturing and chronicling in my journal for years, but hadn't thought of | Transcription |

| 2:26 - 2:28 | myself as making poetry. | Transcription |

| 2:28 - 2:41 | Interestingly enough though, one summer as a child, I spent my whole summer writing a novel. What I thought was a novel. And I think I was about 10 years old at the time. And this was-- so obviously, | Transcription |

| 2:41 - 2:47 | I was doing this writing, but thinking of myself as a poet, thinking of myself as a writer, that didn't come until much later. | Transcription |

| 2:48 - 3:01 | And it came when I really came into more direct contact with, with the, you know, what we called our living literary ancestors: with those writers out there who are now becoming known as our elders, | Transcription |

| 3:01 - 3:14 | some of whom we brought into our home, to meet and to have readings, present readings to our neighborhood. So when I started to have that sort of close up engagement with some of those writers I said | Transcription |

| 3:14 - 3:22 | 'Aha'. You know, I have to honor this. And, and, you know, do the work to bring that out, bring out the writing. | Transcription |

| 3:22 - 3:29 | I'm not sure everyone's familiar with The Darkroom Collective. I was wondering if you could talk about that a little bit. | Transcription |

| 3:29 - 3:43 | Yes. Yes, The Darkroom Collective, formed in the aftermath of James Baldwin's death. James Baldwin died, I believe in 1987. And I was living at that point in a, in a group house in a-- | Transcription |

| 3:43 - 3:55 | well group house sounds a little odd, but I was living among other writers, artists in this large house in Cambridge, Massachusetts, situated between Harvard and MIT. | Transcription |

| 3:56 - 4:10 | And this was-- and some of the writers that I met were fellow students at Harvard and, and other universities in the Boston-Cambridge area. And we came together because we saw that there was really a | Transcription |

| 4:10 - 4:25 | void in terms of the kind of cultural presentations of writers and artists of color in the Cambridge-Boston area. Notwithstanding the fact that you have these very prominent communi-- universities, | Transcription |

| 4:26 - 4:37 | who have access to all sorts of resources and could bring anyone they wanted to. In fact, Ishmael Reed was at Harvard at that point, and there were other writers in the area, but we did not, were not | Transcription |

| 4:37 - 4:42 | experiencing them in a sort of public way, the few who did come through town. | Transcription |

| 4:42 - 4:54 | So we launched a reading series, to celebrate the work of writers of color, and to also make connections between, to introduce and start relationships between those elder writers and then the emerging | Transcription |

| 4:54 - 5:05 | writers. Between those established writers and ourselves and our friends and all of the other people out in the community that we thought would really want to have some sort of dialogue and fellowship | Transcription |

| 5:05 - 5:16 | with these writers. So we started it in our home, in, in new square, in Central Square, Cambridge. And that was the founding of The Dark Room Collective and reading series. | Transcription |

| 5:17 - 5:22 | What about the writers who were involved in The Darkroom Collective? Who were some of those writers? | Transcription |

| 5:22 - 5:41 | Some of those writers include Thomas Sayers Ellis, John Keene, Kevin Young, Carl Phillips, Tracy Smith. So many people, I mean, we think of it as this huge extended family of writers, | Transcription |

| 5:41 - 5:53 | but I, there were many associations, people who were actually in the collective and then people who were present and contributed to those readings. And so in a sense we consider all of those people | Transcription |

| 5:53 - 6:03 | the collective, as well as the writers that-- and the visual artists and the musicians who were a part of the reading series that we presented over several years time. | Transcription |

| 6:04 - 6:15 | And so some of those names that I mentioned are names that you would know because, you know, they have since become known writers, you know, in their own right, and there are others. And, you know, | Transcription |

| 6:16 - 6:26 | I'm sure I'll think of them later and say, oh, I meant to mention, but all of them. And at some point, we were going around traveling as a group and giving readings together, | Transcription |

| 6:26 - 6:42 | so that the collective had a name, and a sort of tradition as a group of practicing writers, as well as the reading series that brought through many other writers: Derek Walcott, Alice Walker. So many | Transcription |

| 6:43 - 6:55 | other people that I'm forgetting Quincy Troupe, I mean a long, long list, I couldn't even begin to list them here, Michael Harper, Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez, Erica Hunt, Harryette Mullen. So many, | Transcription |

| 6:55 - 6:60 | many writers, and we were privileged and fortunate to be a part of that moment. | Transcription |

| 7:01 - 7:13 | Talk a little bit if you don't mind about how you write. And one thing that always interests me is it seems like writers often have their own kind of sacred space, which is not always | Transcription |

| 7:13 - 7:28 | physical but also holes in time where you go to create what you create, and where and when does that take place for you? What is the perfect writing environment for you or the best that you've been | Transcription |

| 7:28 - 7:30 | able to come by so far? | Transcription |

| 7:31 - 7:41 | Well it changes a lot, but when you talk about it in terms of physical space, as well as psychic space, I would say that memory is one of those psychic spaces for me, that is an | Transcription |

| 7:41 - 7:57 | important writing place. Because so much of my work mines my memories and, and increasingly is starting to think of the whole sort of space of Southern history, Southern Black women's history, recent | Transcription |

| 7:57 - 8:01 | as well as past history as a another sort of psychic space, | Transcription |

| 8:01 - 8:14 | where my writing is taking place as I start to think about those forces, and those people whose lives made-- created mine. And then in terms of physical space, well, I mean I do like to, I've found | Transcription |

| 8:14 - 8:27 | that I sort of need to get out in the world and sort of walk around and be out among nature, you know, and, and be in those particular physical spaces. That aids the writing, as well. | Transcription |

| 8:27 - 8:38 | I used to think that it would, it would be this one particular corner of my house where I have my writing table, but I find that I write a lot more away from that table than I do at the table. And | Transcription |

| 8:38 - 8:51 | then I feel that the writing is, is constantly going on in some sense, as I'm walking through my day's activities. I'm constantly touching base with memories or ideas or, you know, fragments of | Transcription |

| 8:51 - 9:02 | dreams, things that are prompted through, through dream. And so that the writing is a sort of constant meditation that's going on as as well as the actual physical practice of sitting down and putting | Transcription |

| 9:02 - 9:02 | pen to the page | Transcription |

| 9:02 - 9:16 | or going to the computer once I've gotten the writing to a certain point and then feel like I could commit it to the screen as well as the page. So yeah, so those are some of the spaces but I would | Transcription |

| 9:16 - 9:26 | say I think travel for me, instigates a lot of writing. And I've actually written about that, that act of traveling and how it adds to writing. | Transcription |

| 9:26 - 9:40 | So I don't know that there's an ideal or one specific sort of ideal place, but I do feel like psychically it's that space of, of memory and personal history and, and family and regional mythology and | Transcription |

| 9:40 - 9:50 | then physically it's being in touch with the, with the outside world. Being able to be among crowds and watch people move. | Transcription |

| 9:50 - 10:03 | And so I'm often in cafes, or I'm often out sitting in a park, on a park bench. And I think probably a lot of writers would would say that as well. So Yeah, so I think that's maybe something | Transcription |

| 10:03 - 10:05 | fundamental to what we're doing. | Transcription |

| 10:05 - 10:06 | You probably have a coffee card or something. | Transcription |

| 10:07 - 10:09 | Well, so um, yeah. | Transcription |

| 10:09 - 10:25 | Let me ask, could you characterize a Sharan Strange poem? Especially, what interests me is the fact that you have an MFA degree and creative writing programs try to be, it seems, very | Transcription |

| 10:25 - 10:34 | avant garde nowadays, at the cutting edge of writing, and it seems like you're doing something a little different than the, avant garde poets. | Transcription |

| 10:34 - 10:45 | I don't think, I don't think I'm avant garde. I know that I'm not avant garde, and I don't think of myself as being cutting edge, or I don't think-- I know that I'm not trying to | Transcription |

| 10:45 - 10:52 | address particular trends or notions of what is cutting edge in my work. | Transcription |

| 10:53 - 11:08 | I think that's too much to think about, for me, when I'm trying so much to really engage with the raw material of my writing in a, in a very open and forthright way, because, you know, in my | Transcription |

| 11:08 - 11:21 | collection, Ash, it deals very much with my childhood, growing up in rural South Carolina, and it deals a lot with my, you know, family history, family memories, and many of them are painful. | Transcription |

| 11:21 - 11:34 | People have told me, they're, they're personal, they're painful. And, you know, so I've had to do a lot of confronting of very personal issues. And I think that I tend to do that, more so than | Transcription |

| 11:35 - 11:47 | thinking about well, in terms of form, am I you know, am I doing something that's breaking with everything that's come before. I think I'm just concerned to, to write honestly, and as truthfully as I | Transcription |

| 11:47 - 11:51 | can, out of the experiences that I'm trying to address in the work. | Transcription |

| 11:52 - 12:04 | You've called the South, I believe, the funky South, but nevertheless, you're back in the South. Is that by design, do you see yourself as a Southern writer? Is that what you want to be? | Transcription |

| 12:04 - 12:09 | Or is it just a matter of coincidence that you're back in the South practicing your craft? | Transcription |

| 12:10 - 12:21 | Well, it is a little more than coincidence, but I certainly did not come back to the south, to be in the South again to write because I feel like I carry the South with me wherever I | Transcription |

| 12:21 - 12:34 | am. And I do identify myself as a Southern writer. But I think it is interesting to be back in the South after such a long period of time, and after having written this first collection of poems that, | Transcription |

| 12:34 - 12:39 | that dealt with my childhood experiences, and that were painful in certain ways. | Transcription |

| 12:39 - 12:51 | Painful because of, because of the family that I grew up-- out of, and I can't think of that family situation without connecting it to a larger, you know, Southern past. | Transcription |

| 12:51 - 13:05 | And so I feel like through those memories that I have, I carry that sense of South. And I think that in the work that I'm doing, even the more personal family poems, situated poems, I'm still dealing | Transcription |

| 13:05 - 13:17 | with that, that matrix of Southern history and culture and mythology, that, that I came out of, so that whether I'm in the South, or geographically in another place, I carry the South. | Transcription |

| 13:17 - 13:29 | Will you talk about one of the poems from the collection, maybe "Still Life", and tell us a little bit about it and the genesis of the poem itself? | Transcription |

| 13:30 - 13:47 | Okay. Well, as I said I am very much concerned with memory. And also I think of myself as a very visually oriented person. So my poetry is very visually oriented in a sense. And so | Transcription |

| 13:47 - 13:60 | that poem 'Still Life', and the still life alludes as well to the notion of still life in art, you know, the capturing of things, the fixing of a thing in a moment, and in a place. | Transcription |

| 13:60 - 14:15 | And so the memory actually deals with my mother, and an image of my mother, as a child. And how, in that moment of seeing my mother, she became something very idealized and someone very beautiful to | Transcription |

| 14:15 - 14:30 | me. Though, as a Black woman growing up in the South, certainly the culture of the South, the Southern society did not affirm her in that way. And also within-- even within her own family she was not | Transcription |

| 14:30 - 14:32 | affirmed in that way. | Transcription |

| 14:32 - 14:45 | And so the poem sort of plays with that irony-- how, as a child, I see her, you know, as one would see a still life, as one would view an object in a still life, sort of idealized and captured in a | Transcription |

| 14:45 - 14:50 | moment. And I think that's how memory works in certain ways as well so I wanted to address that. | Transcription |

| 14:50 - 15:05 | But it goes on to address in the poem the sort of juxtaposition of that, that memory and that image that I carry, with the reality of my mother's life and my mother's marriage, which was-- and I, as a | Transcription |

| 15:06 - 15:22 | child, witnessing my mother and father's relationship brought many painful memories of being in a relationship with a violent alcoholic, spouse, and having been the child of such a relationship | Transcription |

| 15:22 - 15:22 | herself. | Transcription |

| 15:23 - 15:36 | And so I wanted to address that but I also wanted to address how, even as that was true of my mother's life, I could also think of my mother in a different sense, because, as her daughter, I had to | Transcription |

| 15:36 - 15:51 | claim for myself a more positive, a more affirmative notion of myself in the world. In that family situation, in the South, in the world. And so the poem attempts to address some of those situations, | Transcription |

| 15:51 - 15:53 | some of those relationships. | Transcription |

| 15:53 - 16:07 | That's great. I'm curious about a poem I believe you had, as part of an exhibit for Fela. We used to, when I was coming up, know him as the Nigerian James Brown, but the Black president, | Transcription |

| 16:08 - 16:08 | Fela Kuti? | Transcription |

| 16:09 - 16:21 | Fela Ransome Kuti, who then changed his name to Fela Aníkúlápó Kuti, because Aníkúlápó means he who brings death in his pouch, or carries death in his pouch. But that gets back to the | Transcription |

| 16:21 - 16:24 | question about the funky South, too, that you asked me earlier. | Transcription |

| 16:24 - 16:25 | Oh, talk about that. | Transcription |

| 16:25 - 16:36 | Yes, well I did write the poem about Fela, it was actually a commissioned piece I was asked to do, to contribute to the catalog for the exhibition Fela: Black President, which was at | Transcription |

| 16:36 - 16:46 | the new Museum of Contemporary Art in New York. And so what I was trying to address in that poem, it's a, really a sort of, poem-- essay-as-poem. | Transcription |

| 16:46 - 16:58 | I was talking about Fela's influence on my conception of Africa. And so growing up in the South, in the '60s and '70s, I was born in 1959. | Transcription |

| 16:58 - 17:11 | So I was, you know, growing-- my very early years, and my very first memories, and especially my political memories, had to do with, you know, segregation, had to do with this notion of, you know, of | Transcription |

| 17:11 - 17:24 | white supremacy and, and, and the devaluing of Black people and Black people's culture and history. And so I remember, at a very early age, some of the sort of statements that were being made. My | Transcription |

| 17:24 - 17:30 | first political memory was of Strom Thurmond saying that blacks would never get to vote in South Carolina, as long as he was in office. | Transcription |

| 17:31 - 17:43 | So these are things that I carried inside of me. But I also then, you know, alongside that is a very rich and vibrant culture, obviously, that you know, that all Black children growing up are, you | Transcription |

| 17:43 - 17:50 | know, participating in if not even aware of, of all of its dimensions. But one dimension of it for me was James Brown. | Transcription |

| 17:50 - 18:03 | You know, so James Brown-- you know, so we're growing up, you know, young, poor kids, not necessarily able to read all the poetry and things that I would come to later, but we were listening to James | Transcription |

| 18:03 - 18:16 | Brown, we were hearing James Brown. And, you know, soul. Soul. Say it loud, I'm Black and I'm proud. And then this, you know, evolution of soul into funk that James Brown then brought into his, his | Transcription |

| 18:17 - 18:24 | music as well. So of course, what was happening over in Africa with Fela, is that Fela was being exposed to James Brown as well. | Transcription |

| 18:25 - 18:38 | So some point later, you know, in my evolution in my history, I bring these things together. But I call myself a product of the funky South, because that's what I came out of. James Brown, and those | Transcription |

| 18:38 - 18:48 | soul singers, the r&b singers, and then later, the funk singers. Parliament-Funkadelic, all these people we're listening to and dancing to in my backyard growing up. | Transcription |

| 18:48 - 19:01 | So, when I think about, you know, now the moniker is the dirty South. So I distinguish that I'm of that era of the funky South, and, you know, and James Brown. And so I do talk about that, in the | Transcription |

| 19:01 - 19:08 | poem, the Tribute to Fela. That that was a very much, I think, a merging of our two worlds. | Transcription |

| 19:09 - 19:21 | Hearing you differentiate between the funky South and dirty South spoke to my mind of another kind of differentiation that I'm hearing that you're a part of, and that's as being a new | Transcription |

| 19:21 - 19:35 | millennial Black poet. Which, you know, once that label is put out there, it means there's some difference between those who are millennial and I understand it as defined as poets who, in their 30s, | Transcription |

| 19:35 - 19:43 | who are younger, who published books. And how do you feel about that being a new millennial, African American poet? | Transcription |

| 19:45 - 19:55 | Well, I'm not sure about the term. I'm trying to-- I think things haven't changed a whole lot in a sense and so I feel like you know, we're in this new millennium, but when we think | Transcription |

| 19:55 - 20:08 | about some of the, the political issues, the issues of economic and social justice, justice that we're addressing, you know, it doesn't seem like we're, you know, we, you know, embarking on a new | Transcription |

| 20:08 - 20:15 | frontier. But of course we are in the sense that the, the tradition of the art continues to evolve. | Transcription |

| 20:15 - 20:27 | And so what some of the younger writers are doing is they're addressing some of those themes, but they're, they're bringing different styles and different forms to it. And so-- well, I always tell my | Transcription |

| 20:27 - 20:42 | students, well, you know, this spoken word generation is your generation. I sort of fall somewhere in between, you know, sort of in that little space, you know, preceding or maybe right on the verge | Transcription |

| 20:42 - 20:46 | of it. So, I kind of find myself-- I think I'm straddling those different eras. | Transcription |

| 20:46 - 21:01 | So I guess if it's millennial in that sense, I feel like I stand right at that threshold, but what the, what the younger writers are doing, I think, and that, again, mentioning the Dirty South, I | Transcription |

| 21:01 - 21:07 | think that marks you know, the the sort of passing of-- passing into a new era. | Transcription |

| 21:07 - 21:22 | And I think some of that has, for the younger writers, has to do with a new sort of-- well old, as well as new sort of more direct confrontation of some of these social and political issues. I feel | Transcription |

| 21:22 - 21:30 | like the, the connection between what they're doing and the Black Arts Movement poets were doing is, is clear. | Transcription |

| 21:30 - 21:48 | It's been somewhat complicated, I think, by the, the hip hop industry, and some of that cross-pollination or hybridization of the poetic forms because of rap's influence on the younger generation. | Transcription |

| 21:48 - 22:03 | But to me, it seems very much similar to what-- you know, the ways that the Black Arts elders addressed the, the forms that they were working with, they wanted to break with what had come before, and | Transcription |

| 22:03 - 22:12 | actually maybe confront some of the issues, the political and social issues of the day, in a much more direct way. | Transcription |

| 22:13 - 22:27 | So I think that that's what we talk about maybe New Millennium writing, and we think about what the younger writers are doing. And we look at the relationship of hip hop and popular culture to what | Transcription |

| 22:27 - 22:34 | they're doing. I think some of that is, is a part of that notion of New Millennium writing. | Transcription |

| 22:34 - 22:46 | But I think New Millennium writing just means for us that clearly, as we are still confronting, and dealing with, you know, issues of transformation, personal transformation, collective | Transcription |

| 22:46 - 22:60 | transformation, and, and, you know, liberatory impulses among Black writers and Black artists generally, then, what does it mean as far as how the, the tradition of our writing is evolving in terms of | Transcription |

| 22:60 - 23:01 | addressing those issues? | Transcription |

| 23:03 - 23:14 | So, I think that's what we're looking at. I don't know that it's helpful to try to find different terms for it, because it seems to me a sort of continuing same. | Transcription |

| 23:15 - 23:34 | Well, speaking of tradition-- speaking of tradition, l'd like to talk about influence, and some of your specific influences from the African American literary tradition. I think of Alice | Transcription |

| 23:34 - 23:43 | Walker, I guess because [inaudible] to Sarah Lawrence, and also some of her early poems, like in the anthology Black Sister. You have similar lines. | Transcription |

| 23:43 - 23:44 | We do? Okay, okay. | Transcription |

| 23:44 - 23:45 | Yeah, you do. | Transcription |

| 23:46 - 23:57 | I have to admit, I haven't read Alice Walker's poetry very much. But I do feel a cert-- definitely a kinship with her as a writer, as a Southern writer, and certainly some of the | Transcription |

| 23:57 - 24:03 | things that she's addressed in her novels. Yeah, I definitely feel-- so that's interesting I'll have to go back and look at some of those. | Transcription |

| 24:03 - 24:07 | Well what about some of the poets who are influential to your writing? | Transcription |

| 24:08 - 24:19 | Well, you know, Gwendolyn Brooks has certainly been an influence. Not in terms of style, but, you know, certainly in terms of the approach that she took to the writing. Because I think | Transcription |

| 24:19 - 24:36 | Gwendolyn Brooks, is for me, maybe exemplifies for me most what I would like to do in the writing which is to be as open as possible in terms of how I address form, | Transcription |

| 24:36 - 24:52 | but also speaking about the concerns of Black people as a whole, but also Black people as first and foremost human beings. So that we are not separated and isolated from any other writers or any | Transcription |

| 24:52 - 25:01 | other, you know, literary or artistic traditions. That we are very much on a stage with with all of world culture. | Transcription |

| 25:02 - 25:16 | And I really think that she did that in her work even as she talked very specifically about Black women's lives or about poor people's lives, or, you know, as she then she addressed even larger | Transcription |

| 25:16 - 25:30 | political themes in her work. So I, I look to her as someone who is just a guiding-- a mentor in that way. And then some of the contemporary Southern writers like Yusef Komunyakaa. His work has been | Transcription |

| 25:30 - 25:31 | very important to me, | Transcription |

| 25:32 - 25:50 | and especially in terms of, you know, the sort of literary techniques and devices, I'm very much in awe of, you know, his tropes and his imagery. So he's been important. And, you know, Thylias Moss | Transcription |

| 25:50 - 25:59 | who's not a Southern writer, she's a Midwestern writer, but very, I feel very much the the Southern roots of her work as well. | Transcription |

| 25:59 - 25:60 | But that's South anyway. | Transcription |

| 25:60 - 26:14 | Yeah. And so Her work has been important to me. Many others, but I think when I, when I-- Toni Morrison, you know, who I think of, you know, she's a prose writer, but certainly, I see | Transcription |

| 26:14 - 26:18 | her writing as poetry and uh, so she's been very influential. | Transcription |

| 26:18 - 26:37 | And I continue to read, there are other writers, Neruda, whose work has spoken to me quite a great deal. There are other writers I'm not-- a long list, but I think I'll just mention those, especially | Transcription |

| 26:37 - 26:44 | they come to mind. So I think those are important, but there're so many others as well. | Transcription |

| 26:44 - 26:45 | Thank you very much. | Transcription |

| 26:45 - 26:46 | Okay, thank you. | Transcription |

| 26:46 - 26:53 | I can tell you have a lot more you wanted to say. | Transcription |

| 26:53 - 26:53 | Oh. | Transcription |

| 26:56 - 26:58 | If you could just talk to each other, not at the same time. | Transcription |

| 26:58 - 26:60 | It wasn't so bad I hope. Was it? | Transcription |

| 27:02 - 27:11 | No, it wasn't bad. It was good. I feel like yeah, we [inaudible] talk more. Then we'll go out here and we'll say all the-- a whole bunch of other stuff that we could have said on the | Transcription |

| 27:11 - 27:15 | camera tape. Yeah. But um, what else? | Transcription |

| 0:08 - 0:11 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 0:17 - 0:29 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 0:34 - 0:49 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 1:50 - 2:01 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 2:03 - 2:13 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 3:21 - 3:29 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 3:29 - 3:43 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 5:17 - 5:22 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 5:22 - 5:41 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 7:01 - 7:13 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 7:31 - 7:41 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 10:05 - 10:06 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 10:07 - 10:09 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 10:09 - 10:25 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 10:34 - 10:45 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 11:52 - 12:04 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 12:10 - 12:21 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 13:17 - 13:29 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 13:29 - 13:47 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 15:53 - 16:07 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 16:09 - 16:21 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 16:24 - 16:25 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 16:25 - 16:36 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 19:09 - 19:21 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 19:45 - 19:55 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 23:15 - 23:34 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 23:43 - 23:44 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 23:44 - 23:45 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 23:46 - 23:57 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 24:03 - 24:07 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 24:08 - 24:19 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 25:58 - 25:60 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 25:60 - 26:14 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 26:44 - 26:45 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 26:45 - 26:46 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |

| 26:45 - 26:53 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 26:58 - 26:60 | Reggie Young | Speaker |

| 27:02 - 27:11 | Sharan Strange | Speaker |