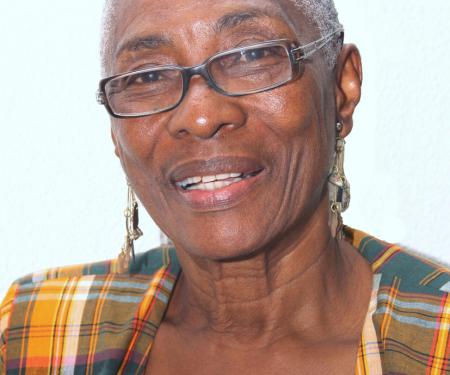

Velma Pollard

Velma Pollard is a Jamaican poet and educator. She attended the University College of the West Indies for her undergraduate studies, where she studied alongside many now renowned poets. Until her recent retirement, Pollard served as a professor of UWI at Mona, and served as the Dean of the Faculty of Education. She has published multiple poetry collections, including Shame Trees Don’t Grow Here and Leaving Traces. She has also published multiple short story collections, and a novella, Karl and Other Stories, which won the Casa de las Americas award in 1992.

In her collection, Shame Trees Don’t Grow Here, Pollard emphasizes the importance of cultivating moral consciousness, and the consequences of neglecting it. Her poems cover the destructive forces of colonialism and capitalism on indigenous populations, her experiences in the U.S. and England, and descriptions of Caribbean landscapes. She continues these themes in The Best Philosophers I Know Can’t Read or Write, infusing her personal poems with Caribbean history, and reimagining pre-colonial indigenous cultures. She also reimagines the traditional wisdom of African folktales and proverbs.

In addition to her works of literature, she has published essays in journals such as Callaloo and Carribean Quarterly, and a linguistic study on Dread Talk and its relation to Rastafarianism.

In this interview with Daryl Dance, Velma Pollard discusses her friendships and connections with many well-known Caribbean poets, her experience teaching in the United States, her writing process, and the themes of her poetry.

Daryl Dance is an educator, specializing in African American folklore, who earned her Ph.D. at the University of Virginia. She taught at Virginia Commonwealth University and the University of Richmond for decades. She has published several works, including Shuckin’ and Jivin’ and Long Gone. In 2013, she was named the Sterling A. Brown Professor of English at Howard University. In 2011, the Daryl Cumber Dance Lifetime Achievement Award was established in her honor through the CLA.

More Information:

Interviews:

Interview with Daryl Dance. Pollard discusses the ideas of exile and return in poetry and everyday life, representation of Black voices in children’s literature, and recurring themes in her poems.

Essays:

"Writing Bridges of Sound: Praise Song for The Widow and Louisiana": Pollard compares Paule Marshall and Erna Brodber’s evocations of African diasporic connections through music and poetic sound.

"Dread Talk: The Speech of the Rastafarian in Jamaica": A linguistic and cultural study of Dread Talk as a means of opposing the political oppression of Rastafarians. Pollard includes a short word list to demonstrate this reality, and explores the way Dread Talk resists the formations of Jamaican Standard English.

"The Dust – a Tribute to the Folk": An exploration and celebration of Carribean folkways, and the deep truth they lend to literature and life philosophy.

Poetry:

Collection of poems by Pollard. Includes a short biographical introduction, and audio of Pollard reading.

Preferred Citation:

Velma Pollard Interview, 9/23/2004 (FF140). Transcribed and edited by Evan Sizemore, 2021-2022, part of the Mellon-funded AudiAnnotate Audiovisual Extensible Workflow Project. Based on video recordings made by WVPT to document the second Furious Flower Poetry Center decennial meeting, September 23-25, 2004. Part of the Furious Flower Poetry Center Conference Records, 1970-2015, UA 0018, Special Collections, Carrier Library, James Madison University Libraries, Harrisonburg, Virginia, media file FF140. Collection finding aid: https://aspace.lib.jmu.edu/repositories/4/resources/487.

Browser Directions:

Audio and video playback is activated by the timestamped annotation section you click in. Search field will find any word or phrase in the Transcription, Speaker or Environment annotation layers. Annotation layers can be ordered by Time (default), Annotation contents or Annotation layer labels by selecting the up/down arrows on the right. Speaker and Transcription layers are matching color-coded to facilitate reading.

| Time | Annotation | Layer |

|---|---|---|

| 4:20 - 4:21 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 4:46 - 4:47 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 7:50 - 7:51 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 7:57 - 7:59 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 22:33 - 22:36 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 25:56 - 25:58 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 35:60 - 36:01 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 36:21 - 36:23 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 36:32 - 36:37 | [Whispering] | Environment |

| 36:52 - 36:52 | [Laughter] | Environment |

| 0:11 - 0:15 | --Dance. D-a-r-y-l, C-u-m-b-e-r, Dance, D-a-n-c-e. | Transcription |

| 0:17 - 0:21 | Velma Pollard, P-o-l-l-a-r-d. | Transcription |

| 0:25 - 0:33 | Velma, tell me what it means to you as a poet, and as a West Indian poet, to be a part of this Furious Flower conference. | Transcription |

| 0:35 - 0:53 | I am overwhelmed. I am flattered. I feel very special. I don't know why me. Chance is something else. If Joanne Gabbin had never met me, she would never have heard my name. If she | Transcription |

| 0:53 - 1:05 | didn't know you, she would never have met me. Because it's through you that she met me. If you had never come to Jamaica, you would never have met me. So it's chance, all the time. | Transcription |

| 1:05 - 1:06 | Everything, I suppose. | Transcription |

| 1:06 - 1:07 | And I'm grateful. | Transcription |

| 1:08 - 1:15 | Have you personally been affected by African American poets and poetry, in your own development as a poet? | Transcription |

| 1:16 - 1:29 | I don't know that I can say my own development as a poet, but certainly as a person. And it's hard for me to think what has affected me as a poet. But it's much easier for me to | Transcription |

| 1:29 - 1:39 | understand what has affected me as a person. I came upon African American poetry, and literature generally, seriously in 1968. | Transcription |

| 1:40 - 1:59 | When I got a little work, in Harlem, in a storefront homework center, where I was supervising homework for children who didn't have parents who could do homework with them. I hired some undergraduates | Transcription |

| 1:59 - 2:03 | from Hunter College. And every afternoon, we supervised homework. | Transcription |

| 2:04 - 2:18 | This was my first time living in America. And I thought I need to know about this culture. I don't know. I knew hardly anything about it, except for the big names that everybody had read. And so I | Transcription |

| 2:18 - 2:24 | started to read. And I read and read and read, and a whole other world was opened up to me. | Transcription |

| 2:24 - 2:30 | Wonderful. Could you tell me about other influences, early influences, family, place, home, school. | Transcription |

| 2:30 - 2:42 | I think well, home, school, I think school. I think that I was impressed early in terms of poetry by some of the, I suppose some of the big names. I have to say that John Donne, | Transcription |

| 2:42 - 2:59 | although he was a religious man, to some extent, and an English man, and all the rest of it. But I think that very early in life I identified Donne as somebody who I related to. | Transcription |

| 2:59 - 3:12 | His passion, he was a man who was as passionate about a woman as he was about Christ. I mean, some of that poetry moved me as early in high school as I could remember. So that's where I remember | Transcription |

| 3:12 - 3:13 | first. | Transcription |

| 3:15 - 3:29 | You know, when I was at UWI, University of the West Indies in 1978, I always felt such a sense of awe to be in the presence of so many literary people. And I'd just like to know | Transcription |

| 3:29 - 3:35 | what it meant to you to go to school there, to work there from all those years from the 1950s onward, | Transcription |

| 3:35 - 3:50 | and to associate with notables at one time or another, such as Derek Walcott, Orlando Patterson, Jean D'Costa, Garth St. Omer, Sylvia Wynter, John Hearne, Slade Hopkinson, Mervyn Morris, Kamau | Transcription |

| 3:50 - 4:04 | Brathwaite, Olive Senior, Pamela Mordecai, Lorna Goodison, Vic Reid, Louise Bennett, Ken Ramchand, Rex Nettleford, Eddie Baugh, Dennis Scott, Tony McNeill, Lorna Goodison, and of course your sister | Transcription |

| 4:04 - 4:07 | Erna Brodber. What's it like to interact with-- | Transcription |

| 4:07 - 4:16 | The thing is that I am lucky that as you were calling those names, I was thinking-- I have never, I don't think of any of them as literary people, or artists. | Transcription |

| 4:16 - 4:18 | But you can't think of West Indian literature without thinking of-- | Transcription |

| 4:18 - 4:28 | But I don't think of West Indian literature. Those people are all people that I have known. I mean, I went to university with Eddie Baugh, Mervyn Morris, Garth St. Omer, the lot of | Transcription |

| 4:28 - 4:38 | them. The things I remember about them are unspeakable. They wouldn't want to remember the things that I remember about them. You know? I remember Garth St. Omer jumping over a fence to prevent me | Transcription |

| 4:38 - 4:46 | from doing something I would have been unhappy to have done. To go and spy on somebody. And he just stopped me and said you are not going. | Transcription |

| 4:46 - 4:58 | I don't remember that he has written novels, I remember that. You know, or I remember walking home from the union with Slade Hopkinson and those guys and just-- people mocking each other's accents | Transcription |

| 4:59 - 5:06 | because we're all from different islands. Things like that that are not at all literary. So because I knew all these people before they became important, it-- | Transcription |

| 5:06 - 5:10 | Well in later years tell me about interactions. I know you've collaborated, | Transcription |

| 5:11 - 5:25 | Yeah, well the interaction at this-- now when I came back onto the campus, and all my little friends were now important people, this was awe. I remember going to an eight o'clock class | Transcription |

| 5:25 - 5:36 | to hear Mervyn Morris lecture and losing my one gold earring. And I said now, why was I even at that lecture at eight in the morning, who invited me? But I didn't know Mervyn as a lecturer or | Transcription |

| 5:36 - 5:37 | anything. | Transcription |

| 5:38 - 5:50 | Or going to hear Eddie Baugh. Talk about Brathwaite's-- there's this poem called Rights [of Passage]. Eddie Baugh gave a phenomenal lecture on Rights. And he read from that poem. You | Transcription |

| 5:50 - 6:02 | know, Eddie Baugh's voice is the best thing in the Caribbean. Reading Kamau Brathwaite. That was like 19-- I came back in 1975. So that may have been '75 or '76. And I recognized that the little | Transcription |

| 6:02 - 6:07 | people that I had known, had grown. They had become mountains. | Transcription |

| 6:07 - 6:08 | Do you remember where you--? | Transcription |

| 6:08 - 6:08 | I said-- hmm? | Transcription |

| 6:09 - 6:14 | I'm sorry, do you remember where you were when you found out that Derek was a Nobel Laureate? | Transcription |

| 6:16 - 6:27 | I must have heard about it before I saw it on the-- I can't remember where I heard. I know that I was at the TV to watch him receive the prize. And I really was overwhelmed. Well, the | Transcription |

| 6:27 - 6:39 | first thing I did when I heard that he got it, I phoned a young American scholar who I know who had told me that he would never get it because of The Boston Sun. | Transcription |

| 6:39 - 6:40 | Oh, yes. | Transcription |

| 6:40 - 6:57 | And I said, people know that it's not his private life that they're giving him the prize for. In any case, most West Indians don't believe that story in that way. Because people | Transcription |

| 6:57 - 7:10 | in the Caribbean are accustomed to saying things to people that they don't really mean all the time. I read Walcott's poetry, and I see some of it and I read the way that people analyze it, and the | Transcription |

| 7:10 - 7:14 | high sounding words they say about it. | Transcription |

| 7:15 - 7:17 | And I say-- I'll give you one quick example. | Transcription |

| 7:17 - 7:17 | Yes, please. | Transcription |

| 7:18 - 7:30 | This is one of my favorite Walcott poems. It is, I think it's called The Light of the World. A lot of people have written a lot about it, it's supposed to be a poem from which | Transcription |

| 7:31 - 7:43 | another life came or something. All kinds of things have been said about it. But the lines where he says, "O beauty, you are the light of the world!" Oh, they have gone to Italy, they have gone to | Transcription |

| 7:43 - 7:45 | everywhere, to assess it. | Transcription |

| 7:46 - 7:59 | And I know that Caribbean men say things like this to women all the time. Oh, lady, Moses must have been sleeping when one like you left heaven. Who knows if Moses was even in heaven? But that kind of | Transcription |

| 7:59 - 8:10 | thing is said, so "O beauty, you are the light of the world!" And I say, you know, they've said everything about it but they have not said this is a man as they would say in Ghana souring a woman. | Transcription |

| 8:10 - 8:22 | Yes, yes. You know, Velma, when you told me about that, it reminded me of what I know once about you're giving a book to a publisher, and his offering to have somebody check the | Transcription |

| 8:22 - 8:23 | Creole for you. | Transcription |

| 8:23 - 8:23 | Yes! | Transcription |

| 8:24 - 8:34 | Talk a little bit about responses from so called, 'First World' publishers and critics and so forth to either your own word or other-- | Transcription |

| 8:34 - 8:49 | Well, in this case, the person they were asking to check my Creole-- unfortunately, I had heard her give a lecture, and her English was not so hot. So I wrote back and I told them that | Transcription |

| 8:49 - 8:55 | what I did for a living was teach people about Creole. Had they known that they may not have suggested this. | Transcription |

| 8:56 - 9:08 | And I said, if you don't want to publish the book, that's fine. But I'm not going to change anything. And since I had tested it and found somebody who does not speak the Creole who was a Canadian | Transcription |

| 9:08 - 9:21 | visitor who didn't have a problem with it. I can write an explanation about the use of the Creole. And so I wrote the afterword, and that satisfied them. Generally speaking, I think it has been a bit | Transcription |

| 9:21 - 9:26 | of a battle that was won before I started writing seriously, was half won. | Transcription |

| 9:27 - 9:38 | The other thing, and here I'm quoting Olive Senior to a certain extent, she was saying once-- and I don't doubt that she remembers saying it-- that she's glad that she was already a professional in | Transcription |

| 9:38 - 9:52 | her own right before she became well known as a writer. And I think I can't use the well known for myself, but I can say that I am also glad that I had sort of made my name professionally before, so | Transcription |

| 9:52 - 9:57 | that I could stand up and say, if you don't want to publish my book, well, that's fine, but this is the situation. | Transcription |

| 9:57 - 10:01 | And to some degree, I guess the generation of Vic Reid and Sam Selvon and those people, yeah, paved the way. Exactly. | Transcription |

| 10:01 - 10:05 | They paved the way for us. This is why I say we benefited from what they did. Yes. | Transcription |

| 10:06 - 10:15 | Velma, let's talk a little bit about your creative process. I remember once you told me you started out writing everything down on a yellow pad. Is that still the way you work? | Transcription |

| 10:15 - 10:29 | I thought this morning as I was sitting in front of you writing in my yellow pad, that maybe you know that a poem is coming, yes. I do not travel without the yellow pad. Sometimes it's | Transcription |

| 10:29 - 10:39 | not yellow, sometimes it's white because sometimes I can't find a yellow pad, but it's mostly yellow-- and a pencil. I don't know why but I really-- I think that what I get from that is the immediacy. | Transcription |

| 10:40 - 10:44 | When I get a thought like what I was writing this morning, it is immediate. | Transcription |

| 10:44 - 10:59 | So when I go back to it, I'm responding to something that was, what Houston Baker just called the... impulse? I like that term. If you wait to write at the computer, or at your desk, you are going to | Transcription |

| 10:59 - 11:06 | lose that. First thing, I don't have the kind of memory that would ever take things with me into when I get comfortable. | Transcription |

| 11:07 - 11:20 | So when it was not the yellow pad, it was a note paper at the kitchen table when I had less time for myself. And I was always busy. And even now if I go to sleep, I always have a pencil and a page. I | Transcription |

| 11:20 - 11:33 | fold the computer sheet the used sheets over. And I always have that and a pencil on my bed. I may write something to buy in the supermarket tomorrow, or I may write a line. | Transcription |

| 11:33 - 11:38 | But when you say, when you had less time for yourself are you speaking of when you had a family? | Transcription |

| 11:38 - 11:44 | Bringing up children working on, you know, doing more things than I should have to do. Yes, that's-- | Transcription |

| 11:46 - 11:53 | Would you share with us one of your favorite poems and tell us a little something about its history and its composition? | Transcription |

| 11:54 - 12:04 | Well, I'm not sure that this is my favorite poem, but I think it's other people's, because it is my most anthologized poem. And it did come out in the first six or so poems that I had | Transcription |

| 12:04 - 12:17 | published. So it's an old poem. Pam Mordecai put together, Pam Mordecai and Mervyn Morris put together Jamaica Woman in 1980 before any of the women in here had their own collections out yet, | Transcription |

| 12:18 - 12:21 | and this was included. It's called Fly. | Transcription |

| 12:21 - 12:38 | "ef a ketch im/ a mash im/ ef a ketch im/ a mash im/ ef a catch im...// Will you walk into my parlour/ Said the spider to the fly/ It's the prettiest snugliest parlour/ that ever you did spy... And I/ | Transcription |

| 12:39 - 12:56 | the fly/ inspecting your web/ this skein now then that/ put my microscope eye/ through its intricate weave/ saw valleys of cloud/ blue and serene/ saw acres of grass/ sheltered and green./ Ephemeral | Transcription |

| 12:56 - 13:06 | and light/ I rested my life/ and dazzled/ I watched/ you wove me inside/ and dazzled/ I slept/ my chrysalis sleep...// | Transcription |

| 13:06 - 13:22 | *** I woke up inside/ no more dazzled and green./ Awake and alert/ unfolding my wings/ I stretched/ But your skeins/ not delicate now/ resistant and strong/ they wove me inside/ I am trapped/ I can't | Transcription |

| 13:22 - 13:24 | move/ I can't butterfly/ fly// | Transcription |

| 13:25 - 13:35 | And you/ perched outside/ your eyes large and clear/ you see acres of green/ you see valleys of cloud/ you can move/ you can fly.../ | Transcription |

| 13:36 - 13:53 | Now I look through the web/ I look into the void/ I see numberless flies/ training microscope eyes/ through intricate weave/ ANANSI I cry/ ANANSI-SI-SI I hear/ the sky is too vast/ how it scatters my | Transcription |

| 13:53 - 14:06 | cry/ the sky is too clear/ it hides my despair/ they can't hear/ they can't see/ with their microscope eye...// ef a ketch im/ a mash im/ ef a ketch im/ a mash im// A ketch im... im... im//" | Transcription |

| 14:08 - 14:10 | Is that an autobiographical poem? | Transcription |

| 14:11 - 14:24 | The thing is, it might be, but I really do not know. Because I think I may have started out by thinking 'ef a ketch im/ a mash im/ ef a ketch im/ a mash im', which is the way the train | Transcription |

| 14:24 - 14:34 | goes up the hill in Jamaica, 'ef a ketch im/ a mash im/ ef a ketch im/ a mash im'. And our trains have to-- used to, we have no trains now-- used to go up very steep hills. | Transcription |

| 14:34 - 14:47 | I think it started with a notion that when we were saying it in elementary school, we were not really listening to the words, that it is a cruel refrain. In other words, if anybody's on the train | Transcription |

| 14:47 - 14:56 | line, when the train is coming, the person is going to die. So, 'ef a ketch im/ a mash im'. I think that's where it started that kind of realization. | Transcription |

| 14:57 - 14:60 | But no thought of the woman entrapped by the rails. | Transcription |

| 14:60 - 15:02 | And then, I was about to say, | Transcription |

| 15:02 - 15:02 | Oh, I'm sorry. | Transcription |

| 15:02 - 15:14 | it moves to the woman entrapped. And not just me, but all other women, I mean, running for that trap rushing to get to the point where you want to go to the cinema but you have to go | Transcription |

| 15:14 - 15:30 | home to cook. Women rush to get to it. And then they realize. Too late, I suppose. It is a very cynical poem but I didn't think it was cynical when I was writing it. But the more I read it, the more | Transcription |

| 15:30 - 15:31 | it sounds cynical. | Transcription |

| 15:31 - 15:35 | Is it simply that you've moved on to another period so that you aren't quite the feminist? | Transcription |

| 15:35 - 15:36 | As trapped? | Transcription |

| 15:36 - 15:40 | Well, quite the feminist that I think I hear there. | Transcription |

| 15:40 - 15:55 | Well, and people accuse me of that. But I don't know if feminist is just realist. Perhaps reality is what they call feminism, you know, just describing the truth. | Transcription |

| 15:55 - 15:59 | Okay. And talk a little bit about Anansi, and using that-- | Transcription |

| 15:59 - 16:10 | Anansi. Well, you know, Anansi is the patron saint of insects in a sense. Anansi, and I've used Anansi a lot. I have a collection called Anansesɛm which is a word for Anansi | Transcription |

| 16:10 - 16:31 | stories, a word from Twi in Ghana. Anansi came to us from Twi, from the Akan tradition, he is both a spider and a god. For some reason, in Jamaica, he took on a trickster personality. | Transcription |

| 16:32 - 16:47 | But, and a trickster personality that I consider to have been much maligned. Anansi gets the better of people, but gets the better of people by finding their Achilles heel. I mean, snake was so proud | Transcription |

| 16:47 - 17:02 | of his length and power and what have you. Anansi humbled him by just discovering, you know, what really was at the heart of his notions about himself, and using it. | Transcription |

| 17:02 - 17:14 | So we have all this blame for Anansi. Anansi tricks people and all the rest of it, but Anansi only tricks people who can be tricked. Anansi, I cry. I'm warning them, Look, don't come into this net. | Transcription |

| 17:15 - 17:21 | But only if you can listen, will you hear. So that's, that's Anansi. | Transcription |

| 17:21 - 17:35 | They always talk about Caribbean people, and the Anansi-ism. I'm sure you've heard of it up here, where we come and in no time we have a house and whatever. And it's all because of our tricks. But I | Transcription |

| 17:35 - 17:42 | think Anansi is about taking opportunity when it offers itself, and just looking around and making sure that you see it. | Transcription |

| 17:42 - 17:43 | And much industry. | Transcription |

| 17:43 - 17:55 | And much industry. Anansi, I think, is part of a migrant personality, it need not be a West Indian coming to America or going to England, it could be any migrant going anywhere. And that same person | Transcription |

| 17:55 - 18:07 | at home is quite laid back. People from here come to the Caribbean just to comment on how laid back we are. And then they meet us up here and say how industrious we are. It's the same people. | Transcription |

| 18:07 - 18:08 | Different situation. | Transcription |

| 18:08 - 18:11 | And you know, our Brer Rabbit is brother to Anansi. | Transcription |

| 18:11 - 18:12 | Yeah, right. Yes, I know. | Transcription |

| 18:12 - 18:19 | The very same tales as a matter of fact, of African origin obviously, are told here with Brer Rabbit. | Transcription |

| 18:19 - 18:22 | Maybe a different folk tradition within Africa. | Transcription |

| 18:22 - 18:34 | Exactly. Exactly. Velma, your latest collection of poetry seems so much more reflective about the concerns of aging, and even dying. And I suppose that is a kind of natural | Transcription |

| 18:34 - 18:40 | progression as we age and experience the deaths of our parents and friends and what have you. | Transcription |

| 18:41 - 18:50 | But one in particular, I want to ask you about though you may say something generally about the subject matter and your interest in the kind of subject matter that we see in your poems more recently. | Transcription |

| 18:50 - 19:01 | But one poem, We Are Our Grandmother's concludes, 'I know that I am grand'. Talk a little bit about what you're saying there. | Transcription |

| 19:01 - 19:12 | Gran. Well, that is really harking back to the short story that is not so short about Gran, which is about, which is perhaps my only autobiographical piece about my grandmother. | Transcription |

| 19:13 - 19:24 | And this is a woman who really, I have always had a great respect for. When her husband died she had seven children: one was nine, the oldest, and the youngest was nine months. | Transcription |

| 19:25 - 19:38 | And she-- now, she was not poverty-stricken, I have to admit. There was land, there was a mill and copper, which is what they used to make sugar. But all of that stuff her husband was in charge of and | Transcription |

| 19:38 - 19:51 | he just died quite suddenly. And I remember her at the mill and copper, giving orders to men so much taller and bigger than she was. And just getting out there at six o'clock every morning and doing | Transcription |

| 19:51 - 19:52 | what had to be done and, | Transcription |

| 19:53 - 20:04 | She's established herself as a baker so she was baking, she was selling sugar where people would come to the boiling house to but by the sugar in these pans, sort of, and making sure there was enough | Transcription |

| 20:04 - 20:16 | money to put all the children through school. So whenever I see myself doing something and people say, how do you manage that? I know that I'm not doing much, I'm doing a quarter of what she did. But | Transcription |

| 20:16 - 20:31 | in a sense I am Gran. And I'm not sure which bit of Alice Walker's work I had read. Why I dedicated it to her. Oh, she said, 'We are all grandmothers'. Yes, yes, that's it. That's how that came-- | Transcription |

| 20:31 - 20:42 | You once said that Gran is an excuse to "big up" a strong female symbol of Jamaican peasantocracy. How important do you see that still, in Jamaican society? | Transcription |

| 20:43 - 20:55 | I see its lack, still. And I think that a lot of the people who have gone astray now have not had access to this kind of person, nor respect for this kind of person. Everybody wants to | Transcription |

| 20:55 - 21:08 | get rich very quickly. My grandmother had to do lots of things so that my mother could have a profession, so that she could want me to have a profession. Everybody wants to be well off, or to get | Transcription |

| 21:08 - 21:14 | where I am, and that's not being that well off, but comfortable. Everybody wants to get comfortable in one generation. | Transcription |

| 21:15 - 21:28 | People long ago sacrificed, knowing that the next generation would benefit. Nobody is willing to sacrifice now. That's why we have in Jamaica, young women leaving their babies at home to go to dances. | Transcription |

| 21:28 - 21:38 | Do you know how many children die by fire in my country, because their mothers went to a dance? Went to a dance, and left the children there. | Transcription |

| 21:40 - 21:53 | So it's a kind of-- I think that we need to get back to saying, not that we want them to be downtrodden or anything, but we just want people to take responsibility and to know that there were people | Transcription |

| 21:53 - 21:54 | who take responsibility. | Transcription |

| 21:55 - 22:07 | And the word "peasantocracy", I like it. Because an academic, a social scientist on the campus, spoke tongue in cheek of my sister and I said, ha, they're not poor people my dear, those are from the | Transcription |

| 22:07 - 22:19 | peasantocray. And what he meant is that we grew up in the country and people think, 'where did they even learn to read books?' But there were books, and there was knife and fork and doilies and all | Transcription |

| 22:19 - 22:30 | these little things that you expect in homes of people who have money. So that -ocracy, peasantocracy, he labels for people like us who behave as if we... | Transcription |

| 22:31 - 22:32 | Came from the aristocracy? | Transcription |

| 22:32 - 22:38 | But we don't really. They are from right down there, the peasanto--. So it is a put down, but a nice put down. | Transcription |

| 22:38 - 22:47 | Well, speaking of your sister, we certainly have to get to that famous writer as well. And I'd love for you to share my favorite story, about... | Transcription |

| 22:48 - 22:50 | Oh, you mean how Jane and Louisa came to be published. | Transcription |

| 22:50 - 22:56 | Exactly, Jane and Louisa, of course, is one of the classics of modern Carribean literature, yes. | Transcription |

| 22:56 - 22:59 | Of Carribean literature. Well, my sister is a social scientist. | Transcription |

| 22:59 - 23:02 | Can I interrupt? Could you say your sister's full name? [Inaudible] want to hear it. | Transcription |

| 23:02 - 23:18 | I'll say it. Yes. Well Erna Brodber is my sister. B-r-o-d-b-e-r is my maiden name and her name. She's a social-- a historian, a social scientist, and what have you. | Transcription |

| 23:18 - 23:31 | And she had been well known in that she's written things like abandonment of children, yards in the City of Kingston. And that's how she made her name. And then she came up with this volume, which she | Transcription |

| 23:31 - 23:41 | showed me in 1975. She had been dissatisfied with what her social science students had to read. There were no Caribbean models, only things out of America and England. | Transcription |

| 23:41 - 23:55 | So she decided to write something about growing up in Jamaica so that her students could relate to it. What happened to it is that her students never got to it. The literary people appropriated it, | Transcription |

| 23:55 - 24:06 | and it has become a Carribean classic. But she, when I reached home in 1975, she had this manuscript and I read it and I said, This is magnificent what's going on here? So I made 12 copies and sent it | Transcription |

| 24:06 - 24:15 | out to some friends and had them comment on it. And Gordon Rohlehr, who is a quite famous Carribean critic was as excited as I was. | Transcription |

| 24:15 - 24:30 | And he said, "Well, you know, this just has to come out". He has a very slow delivery, but anyway. I was going to London for some other reason. And I took it with me on his advice to John La Rose, who | Transcription |

| 24:30 - 24:34 | publishes New Beacon, who grabbed it and published it. And that's the tale. | Transcription |

| 24:34 - 24:35 | And the rest is history. | Transcription |

| 24:35 - 24:47 | The rest is history. Since then, La Rose, New Beacon has published two other novels of hers and what have you. She has continued writing and she's writing-- she also has continued | Transcription |

| 24:47 - 25:01 | writing academic things. She has had four academic manuscripts already in one year. Two are out already, and two are in press. And she has a novel coming. She's a very prolific writer, so. | Transcription |

| 25:01 - 25:12 | Tell me about the two of you as writers. Do you often give feedback regarding manuscripts to each other? Or does she not dare that you get your hands on another one of hers before | Transcription |

| 25:12 - 25:13 | she decides what to do with it? | Transcription |

| 25:13 - 25:28 | No. The thing is, the answer is yes and no, because it never works quite like that. Because we have so many other things to deal with, family matters, all kinds of down to earth things. | Transcription |

| 25:28 - 25:42 | But I mentioned in the foreword to one of her books, which she intended to send for you, but Ivan came, so she couldn't get from-- to me. So I didn't see her before I came, so. But she says you will | Transcription |

| 25:42 - 25:46 | get a package with all of them. She'll just wait till the four come out. Four [inaudible], yes. | Transcription |

| 25:46 - 26:04 | But she decided, well, one of my brothers and I decided that she should not be so poor, when she's so bright. So we thought a series of lectures and this became lectures and a meal. You go to Woodside | Transcription |

| 26:04 - 26:16 | on a Sunday, you pay a certain amount of money, and you'll get a lecture and a meal. Well, not many people were interested in this kind of lecture because it was really about Jamaican history and | Transcription |

| 26:16 - 26:20 | sociology, but written in such a way that the man in the street could understand it. | Transcription |

| 26:21 - 26:32 | Was about 10 lectures, and she really worked very hard, preparing them and reading all this stuff. First few, maybe she had 10 people and then maybe five and then soon it was just my brother and I. | Transcription |

| 26:33 - 26:46 | So, anyway, what she got out of it was she put this set of lectures together. Something about I can't remember the whole title, it ends in 'Consciousness', though. And one book is those 12 lectures | Transcription |

| 26:46 - 26:52 | put together. So in that way, I have benefited. I mean, I just sit and listen to her in awe. | Transcription |

| 26:52 - 27:09 | I don't have to read all that stuff, because she has read it. And I just read what she has produced for the man in the street, and so. Or, well, let me see how I benefit from it. I, last year I was an | Transcription |

| 27:09 - 27:16 | online consultant, I think, for a literature course at Fairleigh Dickinson University. | Transcription |

| 27:16 - 27:28 | So when they asked me a question that I didn't understand, you're online so you don't have to answer immediately. I would telephone her and get the absolute accurate answer. Something about, say Kamau | Transcription |

| 27:28 - 27:40 | Brathwaite in the '70s before I came back to Jamaica, and she would know. So I would get absolutely the right answer. And let me say in terms of an earlier question, what does it feel like to be part | Transcription |

| 27:40 - 27:42 | of this community of writers? | Transcription |

| 27:42 - 27:56 | What it really, how it really works is that they are accessible to me. If I want to remember a line of Walcott, say. I was writing an article on the sewing machine, which is one of my favorite | Transcription |

| 27:56 - 28:06 | articles now. And I called, I picked-- I knew Walcott said something about it and I just called Eddie Baugh. And I could get the page and the-- everything. I don't have to... I have the books | Transcription |

| 28:06 - 28:07 | upstairs. | Transcription |

| 28:07 - 28:09 | You don't have to go to Google, or the internet. | Transcription |

| 28:09 - 28:19 | No. And then Google wouldn't be able to give me such a precise thing. So, or I call Mervyn Morris, you know, somebody-- people think I have a lot of informations I don't really have. What I have is | Transcription |

| 28:19 - 28:20 | who to ask. | Transcription |

| 28:20 - 28:20 | The friends, the friends. | Transcription |

| 28:20 - 28:30 | Yes. And they're just there. I leave a message on the machine. And the answer comes back. So they're all very useful to me. I can't tell you how useful they are in those terms. | Transcription |

| 28:30 - 28:43 | Velma, when you were talking about Erna, I wanted to ask you about the poet in the West Indies such as yourself. Erna, we know she's writing prose, but it's so poetic. She | Transcription |

| 28:43 - 28:45 | And she wrote poetry before, I mean. | Transcription |

| 28:43 - 28:43 | certainly-- | Transcription |

| 28:45 - 29:05 | Certainly one of the poets. Are you, by and large, forced to go abroad to America or to Canada or to England to have certain kinds of opportunities and support? Economic support. | Transcription |

| 29:05 - 29:15 | Is it very difficult? Is this why so many of the writers, most of them indeed, live else-- Many of them certainly live elsewhere for much of their careers? | Transcription |

| 29:15 - 29:28 | No, well, these people you asked me about, my set, we are poets and writers after whatever else we are, and that came up in today's, one of the lectures today. | Transcription |

| 29:28 - 29:29 | Which is very much the same here. | Transcription |

| 29:29 - 29:40 | Yes, we are all something else. Olive is seen as a journalist. I keep saying to people who talk about making your living by poetry that if Walcott had enough money, I don't think he | Transcription |

| 29:40 - 29:49 | would be working still. He's still lecturing in two universities. I mean, and if he can't make a living off it who can? | Transcription |

| 29:49 - 29:51 | After a McArthur and a Nobel. | Transcription |

| 29:51 - 30:04 | Yes, which money he has just spent. Not frittered away but, you know, even if you just live the money goes, you know? So I don't think there's-- I don't know any poet, certainly any | Transcription |

| 30:04 - 30:17 | Caribbean poet, who makes a living off poetry. Poetry, nobody even wants to buy poetry. We can try with the novels maybe and even that, you know, but nobody's making money off literature, none of | Transcription |

| 30:17 - 30:17 | them. | Transcription |

| 30:17 - 30:33 | And the business of going abroad too-- I think the going abroad is the generation before mine. Lamming and people like that who saw opportunity, and then not all of them, because some of those writers | Transcription |

| 30:33 - 30:37 | went abroad for different reasons, nothing to do with writing at all. And those of us-- | Transcription |

| 30:37 - 30:38 | And return, like Vic Reid, [inaudible]. | Transcription |

| 30:38 - 30:50 | Well, Vic Reid just went very briefly, I mean he stayed in the Caribbean, he went to Canada on one of these scholarships one time, but if you can make your living, you tend to stay. And | Transcription |

| 30:50 - 30:60 | I'm saying that those who go when-- mostly not because they were writers, but because whatever they were doing, they would make a better living abroad. Those of us who come for once a year or so a | Transcription |

| 30:60 - 31:07 | semester here or there, come to get US money. It's sixty by one. Sixty Jamaican dollars for one US dollar. | Transcription |

| 31:07 - 31:08 | We should certainly-- | Transcription |

| 31:09 - 31:18 | Hey Daryl, [inaudible] there's about time for one more question. And you may have even [inaudible] a follow-up [inaudible]. I was thinking, did you also ask her, since you see | Transcription |

| 31:18 - 31:23 | yourself as something else and a writer, like, where do you find the time? How do you, what's the muse? How do you--? | Transcription |

| 31:23 - 31:31 | Well, what I was thinking about asking, and you can decide what you rather-- to give you a chance. She does so many other things, the work on Rastafarianism, for example, and that | Transcription |

| 31:31 - 31:33 | sort of thing that we haven't touched upon at all. | Transcription |

| 31:33 - 31:34 | Okay, yeah. | Transcription |

| 31:34 - 31:37 | If you want to talk about about that. | Transcription |

| 31:37 - 31:39 | Okay, that's a good question. | Transcription |

| 31:39 - 31:40 | Is that okay? | Transcription |

| 31:40 - 31:41 | Yeah. I mean let's try and get both of them in, because I mean maybe-- | Transcription |

| 31:41 - 31:42 | Okay, what was the other one? | Transcription |

| 31:42 - 31:47 | Was, since you do other things, where is also, as an answer to that, | Transcription |

| 31:47 - 31:48 | Oh, the time. | Transcription |

| 31:48 - 31:52 | Yeah. How do you how do you fit into your life, the writing, how does it happen? | Transcription |

| 31:52 - 32:08 | And then you can get that into this too. Okay. Velma, as someone who's-- mother, grandmother, who's worked as an educator, a teacher, a dean, someone who is a poet, a short story | Transcription |

| 32:08 - 32:15 | writer, a novelist, a linguist, where do you find the time? And how do you fit all of these into your schedule? | Transcription |

| 32:15 - 32:27 | Now, when you put it like that it sounds like a lot of things. And almost as if, really, how can I fit it in. But if I were a carpenter, I would still have had to be making things. In | Transcription |

| 32:27 - 32:44 | other words, the career bit is just there. And I appreciate the fact that I write, because when I-- if I get home, and I'm really fed up with all those meetings, and all the rest of it, I always have | Transcription |

| 32:44 - 32:47 | something on a yellow pad that needs typing out. | Transcription |

| 32:48 - 32:59 | Something that has not been neated up before. So I usually just go to the yellow pad, and now that there is a computer, before that it was a typewriter, and try to type out something neat. And I think | Transcription |

| 32:59 - 33:05 | that that really calms me. And it's a haven to me to move into my creative self. | Transcription |

| 33:06 - 33:19 | And I have written poetry and short fiction a lot. I only wrote the novel, the year I got sabbatical. Before the year began, I had a summer, in a workshop, the University of Miami, and I started the | Transcription |

| 33:19 - 33:26 | novel and finished it during the year. I've never had that kind of time again. And so I have not written another novel. | Transcription |

| 33:26 - 33:38 | But, and I've been very-- when I was dean, I was very resentful. I'm always resentful of administration because I hate it. And because I hate it, I have to try to do it well. And so it takes up all my | Transcription |

| 33:38 - 33:52 | time. And I, so I started writing something called "In Spite of Miss Dean", when I was dean to show that in those four years or three years, I still-- so I wrote a set of vignettes, you may call them | Transcription |

| 33:52 - 33:57 | because they had to be short. The time was so small. "In Spite of Miss Dean". | Transcription |

| 33:57 - 34:09 | Well, poetry. I write more poetry than prose, I think, because poetry can keep on going on in your head while you are working while you are washing while you are cooking. The poetry goes on, and then | Transcription |

| 34:09 - 34:20 | you get a little minute, you scribble it down and leave it. And then you get another minute and you revise it, so I always have poems being revised. I have a folder that every-- whenever I have a | Transcription |

| 34:20 - 34:32 | minute I just pick up that folder. So that I may have written a poem six months ago, and I haven't seen it for a while until I have a chance when I pick up the folder that's on top, I just revise all | Transcription |

| 34:32 - 34:34 | of them. So one, | Transcription |

| 34:34 - 34:35 | So you may be working on five or six at a time? | Transcription |

| 34:35 - 34:46 | So one-- Poems, right. So and they're like 10 thick as I do the revised versions. So when people tell me, 'Oh, I just scribbled a poem, do you want to hear it'? I say no. I don't want to hear it. I | Transcription |

| 34:46 - 34:54 | don't want to hear anything you just scribbled. When I write down something I have to go over it so many times that I don't want to hear anything you-- So the business of fitting in is that its not | Transcription |

| 34:54 - 34:58 | that the time is there. As I say I always have the paper and I write the stuff. | Transcription |

| 34:59 - 35:15 | Now, the business of Dread Talk. I came home in 1975. I had been interested in Rasta before, but I had not lived in Jamaica in my post-University state. And I started going to meetings and | Transcription |

| 35:15 - 35:18 | Rasta was all around me and I am in linguistics. | Transcription |

| 35:18 - 35:33 | And I discovered that the academic world outside was coming to the Caribbean, and writing long papers on very small things, things that I wouldn't have thought were worthy of writing about. So I said, | Transcription |

| 35:33 - 35:47 | I'm gonna write about dread talk. Whereby-- and I mean, I've just kept on writing about it. Now I'm, the last thing I wrote about was, it's a collaborative work myself and our Cuban linguist about | Transcription |

| 35:47 - 35:50 | dread talk in Cuba, which is coming out in a journal. [Inaudible]. | Transcription |

| 35:50 - 35:54 | Well Velma, thank you so much for this opportunity. It's been wonderful to chat with you. | Transcription |

| 35:54 - 35:55 | It's been my pleasure. | Transcription |

| 35:58 - 35:59 | You guys are great, | Transcription |

| 35:59 - 35:59 | Pull back and get a wide shot. | Transcription |

| 35:59 - 35:60 | I mean I, like, have nothing to say. | Transcription |

| 36:01 - 36:02 | Get the wide shot. | Transcription |

| 36:03 - 36:05 | Oh yeah, if you guys would just talk to each other. | Transcription |

| 36:05 - 36:07 | Yes, yeah. Well, what else have we not said? | Transcription |

| 36:08 - 36:09 | When I [inaudible] my voice last year I was so worried about this. | Transcription |

| 36:09 - 36:13 | No, no we haven't mentioned the grandchildren. But anyway, they got left out, | Transcription |

| 36:13 - 36:14 | But if we started on that we'd take up the whole time. | Transcription |

| 36:14 - 36:24 | but next tiiime-- we would never stop, right. Got it? Yes, okay. Well. | Transcription |

| 36:25 - 36:26 | So now the voice for tomorrow. | Transcription |

| 36:26 - 36:32 | Yes. You have to save it tonight. You can't stand in the car and everybody comes to talk to you. | Transcription |

| 36:32 - 36:38 | I know. That's why I'm staying away from some things, but I think I'm going to come back to his poetry readings. | Transcription |

| 36:38 - 36:38 | Yes, tonight, yes. | Transcription |

| 36:38 - 36:40 | That'll give me a chance to just sit and not talk. | Transcription |

| 36:40 - 36:42 | Yes, because you can't talk while they're reading. | Transcription |

| 36:43 - 36:46 | Yeah, because the more I talk, the more problems I have. Can I [Inaudible]? Okay. | Transcription |

| 36:46 - 36:46 | Okay. | Transcription |

| 36:47 - 36:49 | That was great. | Transcription |

| 36:49 - 36:52 | Okay! Thank you so much. | Transcription |

| 0:11 - 0:15 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 0:17 - 0:21 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 0:25 - 0:33 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 0:35 - 0:53 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 1:05 - 1:06 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 1:06 - 1:07 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 1:08 - 1:15 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 1:16 - 1:29 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 2:24 - 2:30 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 2:30 - 2:42 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 3:15 - 3:29 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 4:07 - 4:16 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 4:16 - 4:18 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 4:18 - 4:28 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 5:06 - 5:10 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 5:11 - 5:25 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 6:07 - 6:08 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 6:08 - 6:08 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 6:09 - 6:14 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 6:16 - 6:27 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 6:39 - 6:40 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 6:40 - 6:57 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 7:17 - 7:17 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 7:18 - 7:30 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 8:10 - 8:22 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 8:23 - 8:23 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 8:24 - 8:34 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 8:34 - 8:49 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 9:57 - 10:01 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 10:01 - 10:05 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 10:06 - 10:15 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 10:15 - 10:29 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 11:33 - 11:38 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 11:38 - 11:44 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 11:46 - 11:53 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 11:54 - 12:04 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 14:08 - 14:10 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 14:11 - 14:24 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 14:57 - 14:60 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 14:60 - 15:02 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 15:02 - 15:02 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 15:02 - 15:14 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 15:31 - 15:35 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 15:35 - 15:36 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 15:36 - 15:40 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 15:40 - 15:55 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 15:55 - 15:59 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 15:59 - 16:10 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 17:42 - 17:43 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 18:11 - 18:12 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 18:11 - 18:19 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 18:19 - 18:22 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 18:22 - 18:34 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 19:00 - 19:12 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 20:31 - 20:42 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 20:43 - 20:55 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 22:31 - 22:32 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 22:32 - 22:38 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 22:38 - 22:47 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 22:48 - 22:50 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 22:50 - 22:56 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 22:56 - 22:59 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 22:59 - 23:02 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 23:01 - 23:18 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 24:34 - 24:35 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 24:35 - 24:47 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 25:01 - 25:12 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 25:13 - 25:28 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 28:20 - 28:20 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 28:20 - 28:30 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 28:30 - 28:43 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 28:42 - 28:45 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 28:45 - 29:05 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 29:15 - 29:28 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 29:28 - 29:29 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 29:29 - 29:40 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 29:49 - 29:51 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 29:51 - 30:04 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 30:37 - 30:38 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 30:38 - 30:50 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 31:07 - 31:08 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 31:09 - 31:18 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 31:23 - 31:31 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 31:33 - 31:34 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 31:34 - 31:37 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 31:37 - 31:39 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 31:39 - 31:40 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 31:40 - 31:41 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 31:41 - 31:42 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 31:42 - 31:47 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 31:47 - 31:48 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 31:48 - 31:52 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 31:51 - 32:08 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 32:15 - 32:27 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 35:50 - 35:54 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 35:54 - 35:55 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 35:58 - 35:59 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 36:05 - 36:07 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 36:08 - 36:09 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 36:09 - 36:13 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 36:13 - 36:14 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 36:13 - 36:24 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 36:25 - 36:26 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 36:26 - 36:32 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 36:32 - 36:38 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 36:38 - 36:38 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 36:38 - 36:40 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 36:40 - 36:42 | Velma Pollard | Speaker |

| 36:43 - 36:46 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |

| 36:46 - 36:46 | Speaker Unknown | Speaker |

| 36:49 - 36:52 | Daryl Cumber Dance | Speaker |